| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Note that [link] lists many diagnostic uses for , where “m” stands for a metastable state of the technetium nucleus. Perhaps 80 percent of all radiopharmaceutical procedures employ because of its many advantages. One is that the decay of its metastable state produces a single, easily identified 0.142-MeV ray. Additionally, the radiation dose to the patient is limited by the short 6.0-h half-life of . And, although its half-life is short, it is easily and continuously produced on site. The basic process for production is neutron activation of molybdenum, which quickly decays into . Technetium-99m can be attached to many compounds to allow the imaging of the skeleton, heart, lungs, kidneys, etc.

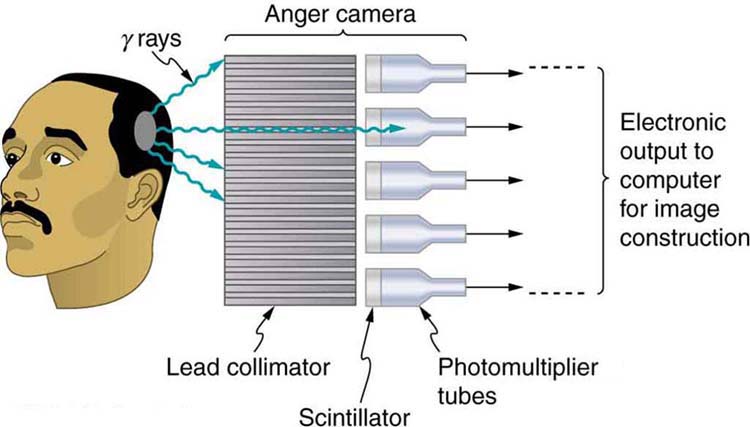

[link] shows one of the simpler methods of imaging the concentration of nuclear activity, employing a device called an Anger camera or gamma camera . A piece of lead with holes bored through it collimates rays emerging from the patient, allowing detectors to receive rays from specific directions only. The computer analysis of detector signals produces an image. One of the disadvantages of this detection method is that there is no depth information (i.e., it provides a two-dimensional view of the tumor as opposed to a three-dimensional view), because radiation from any location under that detector produces a signal.

Imaging techniques much like those in x-ray computed tomography (CT) scans use nuclear activity in patients to form three-dimensional images. [link] shows a patient in a circular array of detectors that may be stationary or rotated, with detector output used by a computer to construct a detailed image. This technique is called single-photon-emission computed tomography(SPECT) or sometimes simply SPET. The spatial resolution of this technique is poor, about 1 cm, but the contrast (i.e. the difference in visual properties that makes an object distinguishable from other objects and the background) is good.

Images produced by emitters have become important in recent years. When the emitted positron ( ) encounters an electron, mutual annihilation occurs, producing two rays. These rays have identical 0.511-MeV energies (the energy comes from the destruction of an electron or positron mass) and they move directly away from one another, allowing detectors to determine their point of origin accurately, as shown in [link] . The system is called positron emission tomography (PET) . It requires detectors on opposite sides to simultaneously (i.e., at the same time) detect photons of 0.511-MeV energy and utilizes computer imaging techniques similar to those in SPECT and CT scans. Examples of -emitting isotopes used in PET are , , , and , as seen in [link] . This list includes C, N, and O, and so they have the advantage of being able to function as tags for natural body compounds. Its resolution of 0.5 cm is better than that of SPECT; the accuracy and sensitivity of PET scans make them useful for examining the brain’s anatomy and function. The brain’s use of oxygen and water can be monitored with . PET is used extensively for diagnosing brain disorders. It can note decreased metabolism in certain regions prior to a confirmation of Alzheimer’s disease. PET can locate regions in the brain that become active when a person carries out specific activities, such as speaking, closing their eyes, and so on.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Basic physics for medical imaging' conversation and receive update notifications?