| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Enzymes are subject to influences by local environmental conditions such as pH, substrate concentration, and temperature. Although increasing the environmental temperature generally increases reaction rates, enzyme catalyzed or otherwise, increasing or decreasing the temperature outside of an optimal range can affect chemical bonds within the active site, making them less well suited to bind substrates. High temperatures will eventually cause enzymes, like other biological molecules, to denature, losing their three-dimensional structure and function. Enzymes are also suited to function best within a certain pH range, and, as with temperature, extreme environmental pH values (acidic or basic) can cause enzymes to denature. Active-site amino-acid side chains have their own acidic or basic properties that are optimal for catalysis and, therefore, are sensitive to changes in pH.

Another factor that influences enzyme activity is substrate concentration: Enzyme activity is increased at higher concentrations of substrate until it reaches a saturation point at which the enzyme can bind no additional substrate. Overall, enzymes are optimized to work best under the environmental conditions in which the organisms that produce them live. For example, while microbes that inhabit hot springs have enzymes that work best at high temperatures, human pathogens have enzymes that work best at 37°C. Similarly, while enzymes produced by most organisms work best at a neutral pH, microbes growing in acidic environments make enzymes optimized to low pH conditions, allowing for their growth at those conditions.

Many enzyme s do not work optimally, or even at all, unless bound to other specific nonprotein helper molecules, either temporarily through ionic or hydrogen bonds or permanently through stronger covalent bonds. Binding to these molecules promotes optimal conformation and function for their respective enzymes. Two types of helper molecules are cofactor s and coenzyme s. Cofactors are inorganic ions such as iron (Fe 2+ ) and magnesium (Mg 2+ ) that help stabilize enzyme conformation and function. One example of an enzyme that requires a metal ion as a cofactor is the enzyme that builds DNA molecules, DNA polymerase, which requires a bound zinc ion (Zn 2+ ) to function.

Coenzymes are organic helper molecules that are required for enzyme action. Like enzymes, they are not consumed and, hence, are reusable. The most common sources of coenzymes are dietary vitamins. Some vitamins are precursors to coenzymes and others act directly as coenzymes.

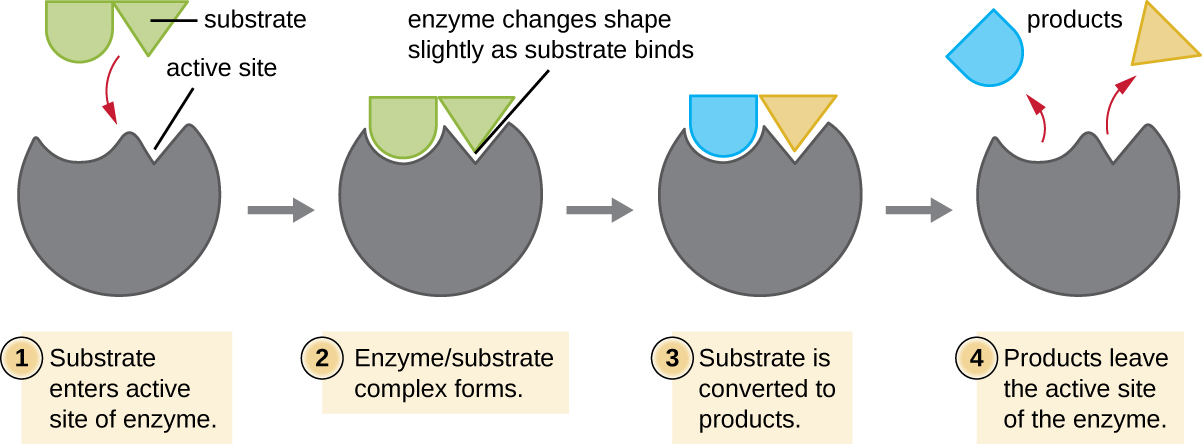

Some cofactors and coenzymes, like coenzyme A (CoA) , often bind to the enzyme’s active site , aiding in the chemistry of the transition of a substrate to a product ( [link] ). In such cases, an enzyme lacking a necessary cofactor or coenzyme is called an apoenzyme and is inactive. Conversely, an enzyme with the necessary associated cofactor or coenzyme is called a holoenzyme and is active. NADH and ATP are also both examples of commonly used coenzymes that provide high-energy electrons or phosphate group s, respectively, which bind to enzymes, thereby activating them.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?