| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

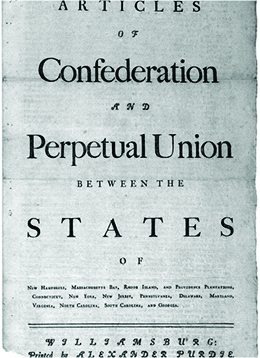

The Articles of Confederation authorized a unicameral legislature, a continuation of the earlier Continental Congress. The people could not vote directly for members of the national Congress; rather, state legislatures decided who would represent the state. In practice, the national Congress was composed of state delegations. There was no president or executive office of any kind, and there was no national judiciary (or Supreme Court) for the United States.

Passage of any law under the Articles of Confederation proved difficult. It took the consensus of nine states for any measure to pass, and amending the Articles required the consent of all the states, also extremely difficult to achieve. Further, any acts put forward by the Congress were non-binding; states had the option to enforce them or not. This meant that while the Congress had power over Indian affairs and foreign policy, individual states could choose whether or not to comply.

The Congress did not have the power to tax citizens of the United States, a fact that would soon have serious consequences for the republic. During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress had sent requisitions for funds to the individual former colonies (now revolutionary states). These states already had an enormous financial burden because they had to pay for militias as well as supply them. In the end, the states failed to provide even half the funding requested by the Congress during the war, which led to a national debt in the tens of millions by 1784.

By the 1780s, some members of the Congress were greatly concerned about the financial health of the republic, and they argued that the national government needed greater power, especially the power to tax. This required amending the Articles of Confederation with the consent of all the states. Those who called for a stronger federal government were known as nationalists. The nationalist group that pushed for the power to tax included Washington’s chief of staff, Alexander Hamilton; Virginia planter James Madison; Pennsylvania’s wealthy merchant Robert Morris (who served under the Confederation government as superintendent of finance in the early 1780s); and Pennsylvania lawyer James Wilson. Two New Yorkers, Gouverneur Morris and James Duane, also joined the effort to address the debt and the weakness of the Confederation government.

These men proposed a 5 percent tax on imports coming into the United States, a measure that would have yielded enough revenue to clear the debt. However, their proposal failed to achieve unanimous support from the states when Rhode Island rejected it. Plans for a national bank also failed to win unanimous support. The lack of support illustrates the Americans’ deep suspicion of a powerful national government, a suspicion that originated from the unilateral and heavy-handed reform efforts that the British Parliament imposed on the colonies in the 1760s and 1770s. Without revenue, the Congress could not pay back American creditors who had lent it money. However, it did manage to make interest payments to foreign creditors in France and the Dutch Republic, fearful that defaulting on those payments would destroy the republic’s credit and leave it unable to secure loans.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?