| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The Maryland and South Carolina constitutions provide examples of efforts to limit the power of a democratic majority. Maryland’s, written in 1776, restricted office holding to the wealthy planter class. A man had to own at least £5,000 worth of personal property to be the governor of Maryland, and possess an estate worth £1,000 to be a state senator. This latter qualification excluded over 90 percent of the white males in Maryland from political office. The 1778 South Carolina constitution also sought to protect the interests of the wealthy. Governors and lieutenant governors of the state had to have “a settled plantation or freehold in their and each of their own right of the value of at least ten thousand pounds currency, clear of debt.” This provision limited high office in the state to its wealthiest inhabitants. Similarly, South Carolina state senators had to own estates valued at £2,000.

John Adams wrote much of the 1780 Massachusetts constitution, which reflected his fear of too much democracy. It therefore created two legislative chambers, an upper and lower house, and a strong governor with broad veto powers. Like South Carolina, Massachusetts put in place office-holding requirements: To be governor under the new constitution, a candidate had to own an estate worth at least £1,000. To serve in the state senate, a man had to own an estate worth at least £300 and have at least £600 in total wealth. To vote, he had to be worth at least sixty pounds. To further keep democracy in check, judges were appointed, not elected. One final limit was the establishment of the state capitol in the commercial center of Boston, which made it difficult for farmers from the western part of the state to attend legislative sessions.

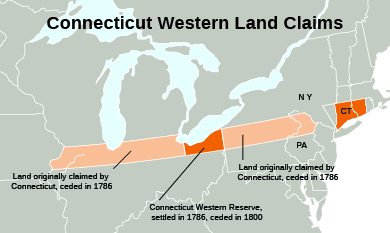

Most revolutionaries pledged their greatest loyalty to their individual states. Recalling the experience of British reform efforts imposed in the 1760s and 1770s, they feared a strong national government and took some time to adopt the Articles of Confederation , the first national constitution. In June 1776, the Continental Congress prepared to announce independence and began to think about the creation of a new government to replace royal authority. Reaching agreement on the Articles of Confederation proved difficult as members of the Continental Congress argued over western land claims. Connecticut, for example, used its colonial charter to assert its claim to western lands in Pennsylvania and the Ohio Territory ( [link] ).

Members of the Continental Congress also debated what type of representation would be best and tried to figure out how to pay the expenses of the new government. In lieu of creating a new federal government, the Articles of Confederation created a “league of friendship” between the states. Congress readied the Articles in 1777 but did not officially approve them until 1781 ( [link] ). The delay of four years illustrates the difficulty of getting the thirteen states to agree on a plan of national government. Citizens viewed their respective states as sovereign republics and guarded their prerogatives against other states.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?