| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

If you look at the Moon through a telescope, you can see that it is covered by impact craters of all sizes. The most conspicuous of the Moon’s surface features—those that can be seen with the unaided eye and that make up the feature often called “the man in the Moon”—are vast splotches of darker lava flows.

Centuries ago, early lunar observers thought that the Moon had continents and oceans and that it was a possible abode of life. They called the dark areas “seas” ( maria in Latin, or mare in the singular, pronounced “mah ray”). Their names, Mare Nubium (Sea of Clouds), Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility), and so on, are still in use today. In contrast, the “land” areas between the seas are not named. Thousands of individual craters have been named, however, mostly for great scientists and philosophers ( [link] ). Among the most prominent craters are those named for Plato, Copernicus, Tycho, and Kepler. Galileo only has a small crater, however, reflecting his low standing among the Vatican scientists who made some of the first lunar maps.

We know today that the resemblance of lunar features to terrestrial ones is superficial. Even when they look somewhat similar, the origins of lunar features such as craters and mountains are very different from their terrestrial counterparts. The Moon’s relative lack of internal activity, together with the absence of air and water, make most of its geological history unlike anything we know on Earth.

To trace the detailed history of the Moon or of any planet, we must be able to estimate the ages of individual rocks. Once lunar samples were brought back by the Apollo astronauts, the radioactive dating techniques that had been developed for Earth were applied to them. The solidification ages of the samples ranged from about 3.3 to 4.4 billion years old, substantially older than most of the rocks on Earth. For comparison, as we saw in the chapter on Earth, Moon, and Sky , both Earth and the Moon were formed between 4.5 and 4.6 billion years ago.

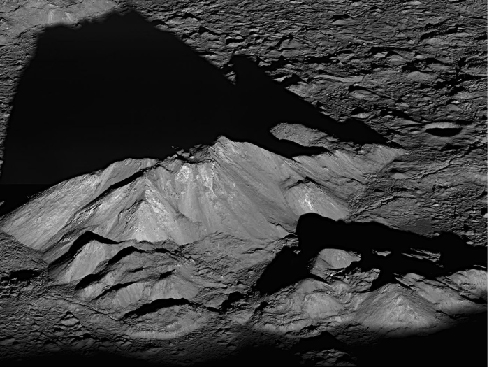

Most of the crust of the Moon (83%) consists of silicate rocks called anorthosites ; these regions are known as the lunar highlands . They are made of relatively low-density rock that solidified on the cooling Moon like slag floating on the top of a smelter. Because they formed so early in lunar history (between 4.1 and 4.4 billion years ago), the highlands are also extremely heavily cratered, bearing the scars of all those billions of years of impacts by interplanetary debris ( [link] ).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?