| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

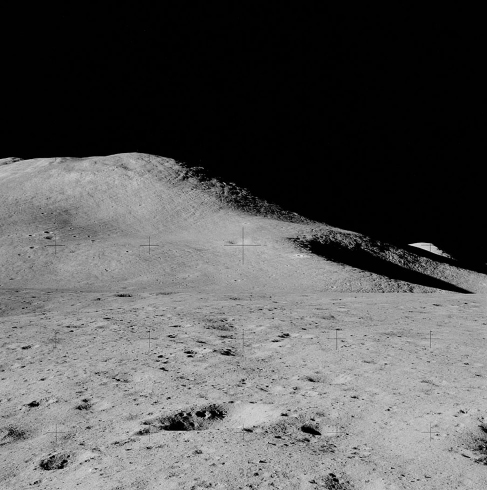

Unlike the mountains on Earth, the Moon’s highlands do not have any sharp folds in their ranges. The highlands have low, rounded profiles that resemble the oldest, most eroded mountains on Earth ( [link] ). Because there is no atmosphere or water on the Moon, there has been no wind, water, or ice to carve them into cliffs and sharp peaks, the way we have seen them shaped on Earth. Their smooth features are attributed to gradual erosion, mostly due to impact cratering from meteorites.

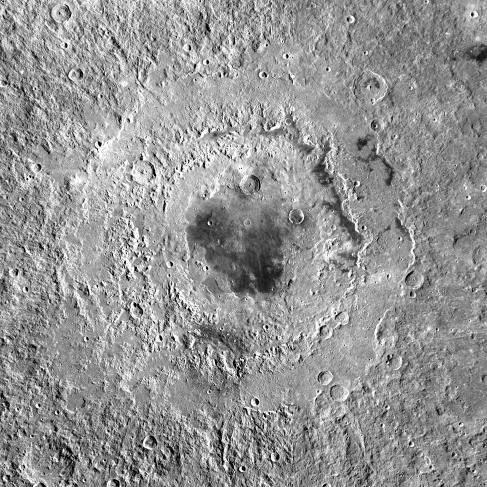

The maria are much less cratered than the highlands, and cover just 17% of the lunar surface, mostly on the side of the Moon that faces Earth ( [link] ).

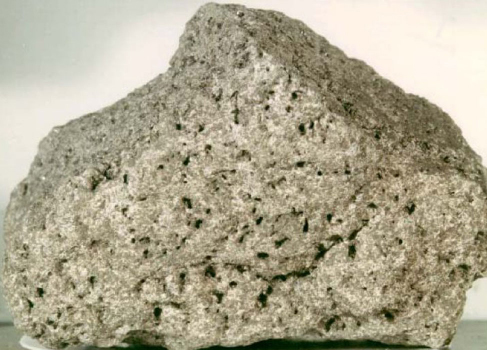

Today, we know that the maria consist mostly of dark-colored basalt (volcanic lava) laid down in volcanic eruptions billions of years ago. Eventually, these lava flows partly filled the huge depressions called impact basins , which had been produced by collisions of large chunks of material with the Moon relatively early in its history. The basalt on the Moon ( [link] ) is very similar in composition to the crust under the oceans of Earth or to the lavas erupted by many terrestrial volcanoes. The youngest of the lunar impact basins is Mare Orientale, shown in [link] .

Volcanic activity may have begun very early in the Moon’s history, although most evidence of the first half billion years is lost. What we do know is that the major mare volcanism, which involved the release of lava from hundreds of kilometers below the surface, ended about 3.3 billion years ago. After that, the Moon’s interior cooled, and volcanic activity was limited to a very few small areas. The primary forces altering the surface come from the outside, not the interior.

“The surface is fine and powdery. I can pick it up loosely with my toe. But I can see the footprints of my boots and the treads in the fine sandy particles.” —Neil Armstrong , Apollo 11 astronaut, immediately after stepping onto the Moon for the first time.

The surface of the Moon is buried under a fine-grained soil of tiny, shattered rock fragments. The dark basaltic dust of the lunar maria was kicked up by every astronaut footstep, and thus eventually worked its way into all of the astronauts’ equipment. The upper layers of the surface are porous, consisting of loosely packed dust into which their boots sank several centimeters ( [link] ). This lunar dust, like so much else on the Moon, is the product of impacts. Each cratering event, large or small, breaks up the rock of the lunar surface and scatters the fragments. Ultimately, billions of years of impacts have reduced much of the surface layer to particles about the size of dust or sand.

In the absence of any air, the lunar surface experiences much greater temperature extremes than the surface of Earth, even though Earth is virtually the same distance from the Sun. Near local noon, when the Sun is highest in the sky, the temperature of the dark lunar soil rises above the boiling point of water. During the long lunar night (which, like the lunar day, lasts two Earth weeks You can see the cycle of day and night on the side of the Moon facing us in the form of the Moon’s phases. It takes about 14 days for the side of the Moon facing us to go from full moon (all lit up) to new moon (all dark). There is more on this in Chapter 4: Earth, Moon, and Sky . ), the temperature drops to about 100 K (–173 °C). The extreme cooling is a result not only of the absence of air but also of the porous nature of the Moon’s dusty soil, which cools more rapidly than solid rock would.

Learn how the moon’s craters and maria were formed by watching a video produced by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) team about the evolution of the Moon, tracing it from its origin about 4.5 billion years ago to the Moon we see today. See a simulation of how the Moon’s craters and maria were formed through periods of impact, volcanic activity, and heavy bombardment.

The Moon, like Earth, was formed about 4.5 billion year ago. The Moon’s heavily cratered highlands are made of rocks more than 4 billion years old. The darker volcanic plains of the maria were erupted primarily between 3.3 and 3.8 billion years ago. Generally, the surface is dominated by impacts, including continuing small impacts that produce its fine-grained soil.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?