| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

History quickly repeated itself. In 1975, the tau ( ) was discovered, and a third family of leptons emerged as seen in [link] ). Theorists quickly proposed two more quark flavors called top ( t ) or truth and bottom ( b ) or beauty to keep the number of quarks the same as the number of leptons. And in 1976, the upsilon ( ) meson was discovered and shown to be composed of a bottom and an antibottom quark or , quite analogous to the being as seen in [link] . Being a single flavor, these mesons are sometimes called bare charm and bare bottom and reveal the characteristics of their quarks most clearly. Other mesons containing bottom quarks have since been observed. In 1995, two groups at Fermilab confirmed the top quark’s existence, completing the picture of six quarks listed in [link] . Each successive quark discovery—first , then , and finally —has required higher energy because each has higher mass. Quark masses in [link] are only approximately known, because they are not directly observed. They must be inferred from the masses of the particles they combine to form.

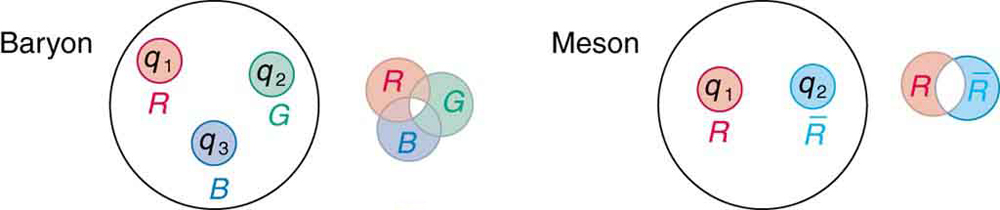

As mentioned and shown in [link] , quarks carry another quantum number, which we call color . Of course, it is not the color we sense with visible light, but its properties are analogous to those of three primary and three secondary colors. Specifically, a quark can have one of three color values we call red ( ), green ( ), and blue ( ) in analogy to those primary visible colors. Antiquarks have three values we call antired or cyan , antigreen or magenta , and antiblue or yellow in analogy to those secondary visible colors. The reason for these names is that when certain visual colors are combined, the eye sees white. The analogy of the colors combining to white is used to explain why baryons are made of three quarks, why mesons are a quark and an antiquark, and why we cannot isolate a single quark. The force between the quarks is such that their combined colors produce white. This is illustrated in [link] . A baryon must have one of each primary color or RGB, which produces white. A meson must have a primary color and its anticolor, also producing white.

Why must hadrons be white? The color scheme is intentionally devised to explain why baryons have three quarks and mesons have a quark and an antiquark. Quark color is thought to be similar to charge, but with more values. An ion, by analogy, exerts much stronger forces than a neutral molecule. When the color of a combination of quarks is white, it is like a neutral atom. The forces a white particle exerts are like the polarization forces in molecules, but in hadrons these leftovers are the strong nuclear force. When a combination of quarks has color other than white, it exerts extremely large forces—even larger than the strong force—and perhaps cannot be stable or permanently separated. This is part of the theory of quark confinement , which explains how quarks can exist and yet never be isolated or directly observed. Finally, an extra quantum number with three values (like those we assign to color) is necessary for quarks to obey the Pauli exclusion principle. Particles such as the , which is composed of three strange quarks, , and the , which is three up quarks, uuu , can exist because the quarks have different colors and do not have the same quantum numbers. Color is consistent with all observations and is now widely accepted. Quark theory including color is called quantum chromodynamics (QCD), also named by Gell-Mann.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics' conversation and receive update notifications?