| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Anyone who believes in indefinite growth of anything physical on a physically finite planet is either a madman or an economist.Kenneth Boulding, economist (President Kennedy's Environmental Advisor 1966)

In biology, a population is a very specific thing. A population is all the members of a species living within a specific area. Populations are typically dynamic entities. They expand and contract, but, as noted above, they cannot expand infinitely. Populations fluctuate based on a number of factors: seasonal and yearly changes in the environment, natural disasters such as forest fires and volcanic eruptions, competition for resources between and within species, and the amount of habitat (where an organism lives). The statistical study of population dynamics, demography , uses a series of mathematical tools to investigate how populations respond to changes in their biotic and abiotic environments. Many of these tools were originally designed to study human populations. For example, life tables , which detail the life expectancy of individuals within a population, were initially developed by life insurance companies to set insurance rates. In fact, while the term “demographics” is commonly used when discussing humans, all living populations can be studied using this approach.

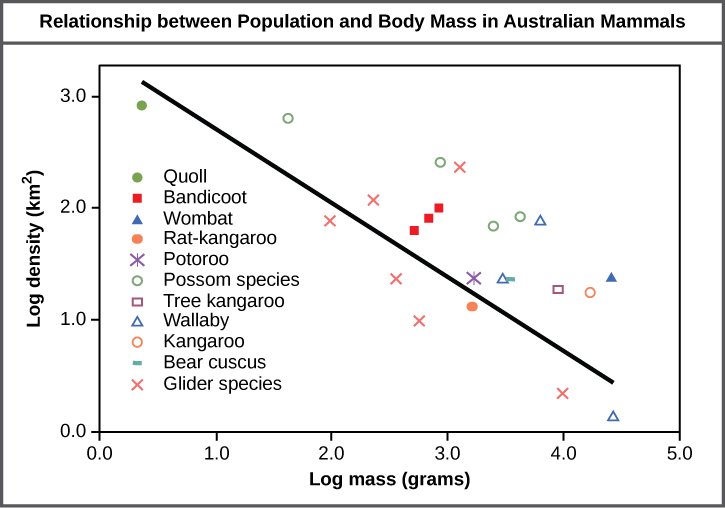

The study of any population usually begins by determining how many individuals of a particular species exist, and how closely associated they are with each other. Within a particular habitat, a population can be characterized by its population size ( N ) , the total number of individuals, and its population density , the number of individuals within a specific area or volume. Population size and density are the two main characteristics used to describe and understand populations. For example, populations with more individuals may be more stable than smaller populations based on their genetic variability, and thus their potential to adapt to the environment. Alternatively, a member of a population with low population density (more spread out in the habitat), might have more difficulty finding a mate to reproduce compared to a population of higher density. As is shown in [link] , smaller organisms tend to be more densely distributed than larger organisms.

The most accurate way to determine population size is to simply count all of the individuals within the habitat. However, this method is often not logistically or economically feasible, especially when studying large habitats. Thus, scientists usually study populations by sampling a representative portion of each habitat and using these data to make inferences about the habitat as a whole. A variety of methods can be used to sample populations to determine their size and density. For immobile organisms such as plants, or for very small and slow-moving organisms, a quadrat may be used ( [link] ). A quadrat is a way of marking off square areas within a habitat, either by staking out an area with sticks and string, or by the use of a wood, plastic, or metal square placed on the ground. After setting the quadrats, researchers then count the number of individuals that lie within their boundaries. Multiple quadrat samples are performed throughout the habitat at several random locations. All of these data can then be used to estimate the population size and population density within the entire habitat. The number and size of quadrat samples depends on the type of organisms under study and other factors, including the density of the organism. For example, if sampling daffodils, a 1 m 2 quadrat might be used whereas with giant redwoods, which are larger and live much further apart from each other, a larger quadrat of 400 m 2 might be employed. This ensures that enough individuals of the species are counted to get an accurate sample that correlates with the habitat, including areas not sampled.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?