| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Find a lightbulb with a filament. Look carefully at the filament and describe its structure. To what points is the filament connected?

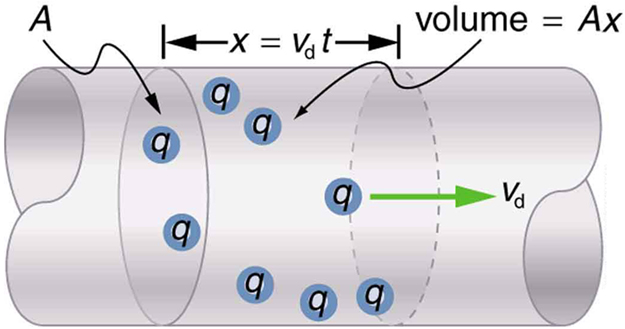

We can obtain an expression for the relationship between current and drift velocity by considering the number of free charges in a segment of wire, as illustrated in [link] . The number of free charges per unit volume is given the symbol and depends on the material. The shaded segment has a volume , so that the number of free charges in it is . The charge in this segment is thus , where is the amount of charge on each carrier. (Recall that for electrons, is .) Current is charge moved per unit time; thus, if all the original charges move out of this segment in time , the current is

Note that is the magnitude of the drift velocity, , since the charges move an average distance in a time . Rearranging terms gives

where is the current through a wire of cross-sectional area made of a material with a free charge density . The carriers of the current each have charge and move with a drift velocity of magnitude .

Note that simple drift velocity is not the entire story. The speed of an electron is much greater than its drift velocity. In addition, not all of the electrons in a conductor can move freely, and those that do might move somewhat faster or slower than the drift velocity. So what do we mean by free electrons? Atoms in a metallic conductor are packed in the form of a lattice structure. Some electrons are far enough away from the atomic nuclei that they do not experience the attraction of the nuclei as much as the inner electrons do. These are the free electrons. They are not bound to a single atom but can instead move freely among the atoms in a “sea” of electrons. These free electrons respond by accelerating when an electric field is applied. Of course as they move they collide with the atoms in the lattice and other electrons, generating thermal energy, and the conductor gets warmer. In an insulator, the organization of the atoms and the structure do not allow for such free electrons.

Calculate the drift velocity of electrons in a 12-gauge copper wire (which has a diameter of 2.053 mm) carrying a 20.0-A current, given that there is one free electron per copper atom. (Household wiring often contains 12-gauge copper wire, and the maximum current allowed in such wire is usually 20 A.) The density of copper is .

Strategy

We can calculate the drift velocity using the equation . The current is given, and is the charge of an electron. We can calculate the area of a cross-section of the wire using the formula where is one-half the given diameter, 2.053 mm. We are given the density of copper, and the periodic table shows that the atomic mass of copper is 63.54 g/mol. We can use these two quantities along with Avogadro’s number, to determine the number of free electrons per cubic meter.

Solution

First, calculate the density of free electrons in copper. There is one free electron per copper atom. Therefore, is the same as the number of copper atoms per . We can now find as follows:

The cross-sectional area of the wire is

Rearranging to isolate drift velocity gives

Discussion

The minus sign indicates that the negative charges are moving in the direction opposite to conventional current. The small value for drift velocity (on the order of ) confirms that the signal moves on the order of times faster (about ) than the charges that carry it.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics ii' conversation and receive update notifications?