| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The eye is perhaps the most interesting of all optical instruments. The eye is remarkable in how it forms images and in the richness of detail and color it can detect. However, our eyes commonly need some correction, to reach what is called “normal” vision, but should be called ideal rather than normal. Image formation by our eyes and common vision correction are easy to analyze with the optics discussed in Geometric Optics .

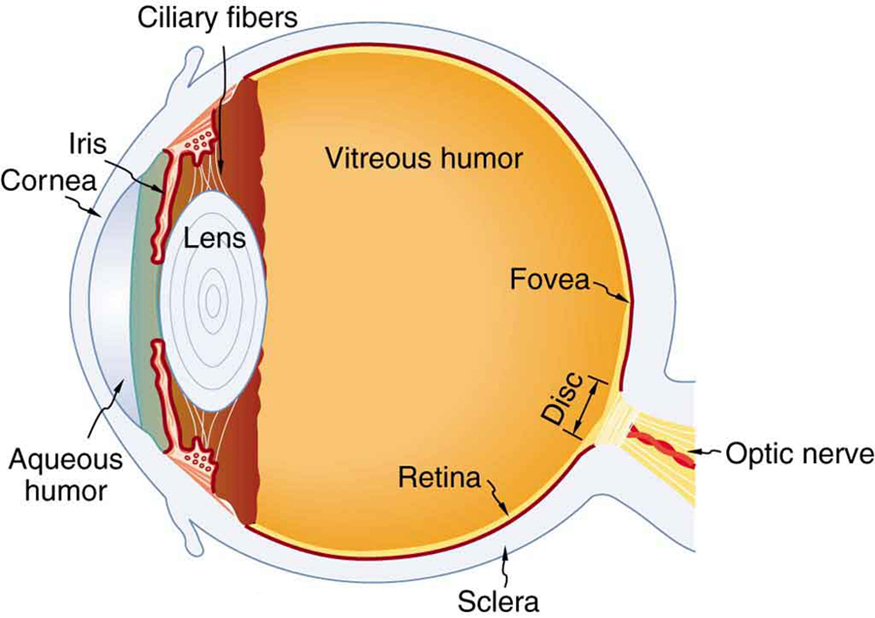

[link] shows the basic anatomy of the eye. The cornea and lens form a system that, to a good approximation, acts as a single thin lens. For clear vision, a real image must be projected onto the light-sensitive retina, which lies at a fixed distance from the lens. The lens of the eye adjusts its power to produce an image on the retina for objects at different distances. The center of the image falls on the fovea, which has the greatest density of light receptors and the greatest acuity (sharpness) in the visual field. The variable opening (or pupil) of the eye along with chemical adaptation allows the eye to detect light intensities from the lowest observable to times greater (without damage). This is an incredible range of detection. Our eyes perform a vast number of functions, such as sense direction, movement, sophisticated colors, and distance. Processing of visual nerve impulses begins with interconnections in the retina and continues in the brain. The optic nerve conveys signals received by the eye to the brain.

Refractive indices are crucial to image formation using lenses. [link] shows refractive indices relevant to the eye. The biggest change in the refractive index, and bending of rays, occurs at the cornea rather than the lens. The ray diagram in [link] shows image formation by the cornea and lens of the eye. The rays bend according to the refractive indices provided in [link] . The cornea provides about two-thirds of the power of the eye, owing to the fact that speed of light changes considerably while traveling from air into cornea. The lens provides the remaining power needed to produce an image on the retina. The cornea and lens can be treated as a single thin lens, even though the light rays pass through several layers of material (such as cornea, aqueous humor, several layers in the lens, and vitreous humor), changing direction at each interface. The image formed is much like the one produced by a single convex lens. This is a case 1 image. Images formed in the eye are inverted but the brain inverts them once more to make them seem upright.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Physics for the modern world' conversation and receive update notifications?