| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

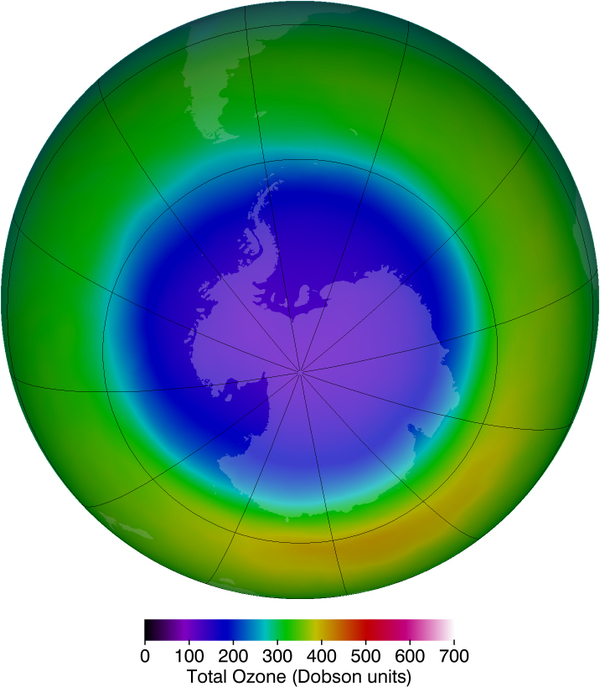

Besides the adverse effects of ultraviolet radiation, there are also benefits of exposure in nature and uses in technology. Vitamin D production in the skin (epidermis) results from exposure to UVB radiation, generally from sunlight. A number of studies indicate lack of vitamin D can result in the development of a range of cancers (prostate, breast, colon), so a certain amount of UV exposure is helpful. Lack of vitamin D is also linked to osteoporosis. Exposures (with no sunscreen) of 10 minutes a day to arms, face, and legs might be sufficient to provide the accepted dietary level. However, in the winter time north of about latitude, most UVB gets blocked by the atmosphere.

UV radiation is used in the treatment of infantile jaundice and in some skin conditions. It is also used in sterilizing workspaces and tools, and killing germs in a wide range of applications. It is also used as an analytical tool to identify substances.

When exposed to ultraviolet, some substances, such as minerals, glow in characteristic visible wavelengths, a process called fluorescence. So-called black lights emit ultraviolet to cause posters and clothing to fluoresce in the visible. Ultraviolet is also used in special microscopes to detect details smaller than those observable with longer-wavelength visible-light microscopes.

In the 1850s, scientists (such as Faraday) began experimenting with high-voltage electrical discharges in tubes filled with rarefied gases. It was later found that these discharges created an invisible, penetrating form of very high frequency electromagnetic radiation. This radiation was called an X-ray , because its identity and nature were unknown.

X-rays can be created in a high-voltage discharge. They are emitted in the material struck by electrons in the discharge current. There are two mechanisms by which the electrons create X-rays.

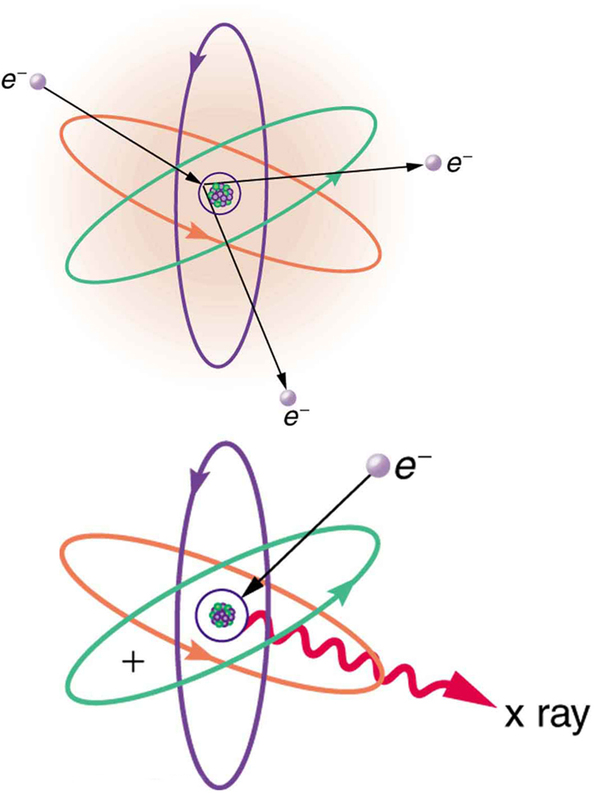

The first method is illustrated in [link] . An electron is accelerated in an evacuated tube by a high positive voltage. The electron strikes a metal plate (e.g., copper) and produces X-rays. Since this is a high-voltage discharge, the electron gains sufficient energy to ionize the atom.

In the case shown, an inner-shell electron (one in an orbit relatively close to and tightly bound to the nucleus) is ejected. A short time later, another electron is captured and falls into the orbit in a single great plunge. The energy released by this fall is given to an EM wave known as an X-ray. Since the orbits of the atom are unique to the type of atom, the energy of the X-ray is characteristic of the atom, hence the name characteristic X-ray.

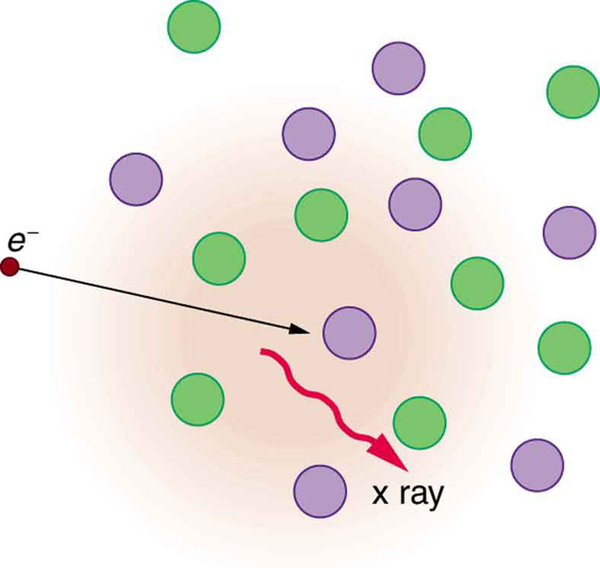

The second method by which an energetic electron creates an X-ray when it strikes a material is illustrated in [link] . The electron interacts with charges in the material as it penetrates. These collisions transfer kinetic energy from the electron to the electrons and atoms in the material.

A loss of kinetic energy implies an acceleration, in this case decreasing the electron’s velocity. Whenever a charge is accelerated, it radiates EM waves. Given the high energy of the electron, these EM waves can have high energy. We call them X-rays. Since the process is random, a broad spectrum of X-ray energy is emitted that is more characteristic of the electron energy than the type of material the electron encounters. Such EM radiation is called “bremsstrahlung” (German for “braking radiation”).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Concepts of physics with linear momentum' conversation and receive update notifications?