| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

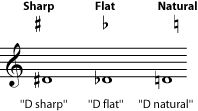

In common notation , any note can be sharp, flat, or natural . A sharp symbol raises the pitch (of a natural note) by one half step ; a flat symbol lowers it by one half step.

Why do we bother with these symbols? There are twelve pitches available within any octave . We could give each of those twelve pitches its own name (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, and L) and its own line or space on a staff. But that would actually be fairly inefficient, because most music is in a particular key . And music that is in a major or minor key will tend to use only seven of those twelve notes. So music is easier to read if it has only lines, spaces, and notes for the seven pitches it is (mostly) going to use, plus a way to write the occasional notes that are not in the key.

This is basically what common notation does. There are only seven note names (A, B, C, D, E, F, G), and each line or space on a staff will correspond with one of those note names. To get all twelve pitches using only the seven note names, we allow any of these notes to be sharp, flat, or natural. Look at the notes on a keyboard.

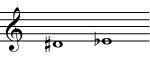

Because most of the natural notes are two half steps apart, there are plenty of pitches that you can only get by naming them with either a flat or a sharp (on the keyboard, the "black key" notes). For example, the note in between D natural and E natural can be named either D sharp or E flat. These two names look very different on the staff, but they are going to sound exactly the same, since you play both of them by pressing the same black key on the piano.

This is an example of enharmonic spelling . Two notes are enharmonic if they sound the same on a piano but are named and written differently.

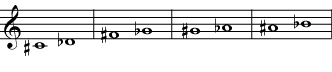

Name the other enharmonic notes that are listed above the black keys on the keyboard in [link] . Write them on a treble clef staff. If you need staff paper, you can print out this PDF file

But these are not the only possible enharmonic notes. Any note can be flat or sharp, so you can have, for example, an E sharp. Looking at the keyboard and remembering that the definition of sharp is "one half step higher than natural", you can see that an E sharp must sound the same as an F natural. Why would you choose to call the note E sharp instead of F natural? Even though they sound the same, E sharp and F natural, as they are actually used in music, are different notes. (They may, in some circumstances, also sound different; see below .) Not only will they look different when written on a staff, but they will have different functions within a key and different relationships with the other notes of a piece of music. So a composer may very well prefer to write an E sharp, because that makes the note's place in the harmonies of a piece more clear to the performer. (Please see Triads , Beyond Triads , and Harmonic Analysis for more on how individual notes fit into chords and harmonic progressions.)

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Music fundamentals 1: pitch and major scales and keys' conversation and receive update notifications?