| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

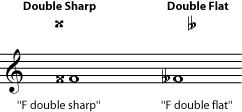

In fact, this need (to make each note's place in the harmony very clear) is so important that double sharps and double flats have been invented to help do it. A double sharp is two half steps (one whole step ) higher than the natural note. A double flat is two half steps lower than the natural note. Double sharps and flats are fairly rare, and triple and quadruple flats even rarer, but all are allowed.

Give at least one enharmonic spelling for the following notes. Try to give more than one. (Look at the keyboard again if you need to.)

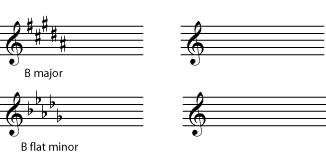

Keys and scales can also be enharmonic. Major keys, for example, always follow the same pattern of half steps and whole steps. (See Major Keys and Scales . Minor keys also all follow the same pattern, different from the major scale pattern; see Minor Keys .) So whether you start a major scale on an E flat, or start it on a D sharp, you will be following the same pattern, playing the same piano keys as you go up the scale. But the notes of the two scales will have different names, the scales will look very different when written, and musicians may think of them as being different. For example, most instrumentalists would find it easier to play in E flat than in D sharp. In some cases, an E flat major scale may even sound slightly different from a D sharp major scale. (See below .)

Since the scales are the same, D sharp major and E flat major are also enharmonic keys . Again, their key signatures will look very different, but music in D sharp will not be any higher or lower than music in E flat.

Give an enharmonic name and key signature for the keys given in [link] . (If you are not well-versed in key signatures yet, pick the easiest enharmonic spelling for the key name, and the easiest enharmonic spelling for every note in the key signature. Writing out the scales may help, too.)

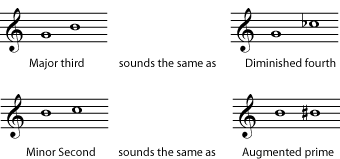

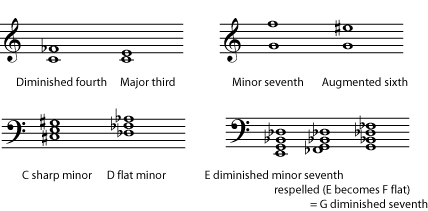

Chords and intervals also can have enharmonic spellings. Again, it is important to name a chord or interval as it has been spelled, in order to understand how it fits into the rest of the music. A C sharp major chord means something different in the key of D than a D flat major chord does. And an interval of a diminished fourth means something different than an interval of a major third, even though they would be played using the same keys on a piano. (For practice naming intervals, see Interval . For practice naming chords, see Naming Triads and Beyond Triads . For an introduction to how chords function in a harmony, see Beginning Harmonic Analysis .)

All of the above discussion assumes that all notes are tuned in equal temperament . Equal temperament has become the "official" tuning system for Western music . It is easy to use in pianos and other instruments that are difficult to retune (organ, harp, and xylophone, to name just a few), precisely because enharmonic notes sound exactly the same. But voices and instruments that can fine-tune quickly (for example violins, clarinets, and trombones) often move away from equal temperament. They sometimes drift, consciously or unconsciously, towards just intonation , which is more closely based on the harmonic series . When this happens, enharmonically spelled notes, scales, intervals, and chords, may not only be theoretically different. They may also actually be slightly different pitches. The differences between, say, a D sharp and an E flat, when this happens, are very small, but may be large enough to be noticeable. Many Non-western music traditions also do not use equal temperament. Sharps and flats used to notate music in these traditions should not be assumed to mean a change in pitch equal to an equal-temperament half-step . For definitions and discussions of equal temperament, just intonation, and other tuning systems, please see Tuning Systems .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Music fundamentals 1: pitch and major scales and keys' conversation and receive update notifications?