| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

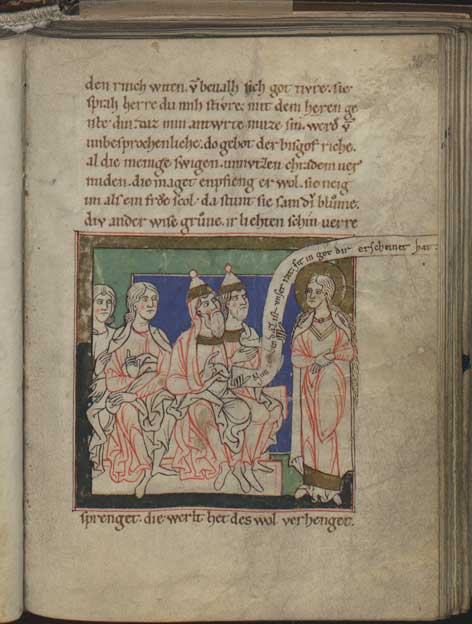

Mary is similarly unwilling. The priest sends for her and commands the crowd to be silent when she appears. The language and the miniature encourage the reader-viewer to feel a part of the crowd whose eyes feast on her and to witness the exchange (Fig. 12; fol. 36r). In the text, the priest tells her that the miracle means “she has no respite or postponement and may no longer argue” [daz wil daz du neheine frist / noh dehein ufscub habest / vnd dih niht lenger entsagest; ll. 2048-50]. The direct words on his banderole order her, “Take Joseph, that is our advice, since God showed him to you” [Nim io[se]ben daz ist unser rat. / sit in got dir erscheinet hat]. Standing very straight, she lifts her chin and grasps her left wrist with her right hand. Iconographically the wrist-grasp gesture has a standard meaning; usually enacted by one person upon another, it signals that the grasper has power of some kind, not necessarily physical, over the other. Employed rather unusually to assert autonomy, here Mary’s gesture functions as a non-verbal equivalent of her speech. In the text she acknowledges the necessity of yielding to God’s will, but nonetheless insists: “My body I give to no one—I remain firm on that” [mins libes ich niemen gan, / da belibe ich staetik an; ll. 2097-98]. Her posture and gesture result from meaningful bodily action that encourages reader-viewers to respond with embodied engagement, that is, to experience in their own bodies, perhaps by means of mirror neurons, her unbending attitude and her determination to retain control over her body.

The sense of witnessing unfolding action in the present, which pervades the visual narrative in this manuscript, seems especially strong in this visual depiction of two forces apparently locked in conflict; it raises a key issue for pictorial narrative, namely the spatialization of time. Art historian Suzanne Lewis offers a brief overview of the problem, pointing out that a traditional view has been that a static picture cannot tell a story, which has to move through time. But more recently, Lewis continues, “the distinction between spatial and temporal arts has become relative, softened and blurred—witness the screen titles in silent films and comic-strip balloons.” Suzanne Lewis, “Narrative,” in A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe , edited by Conrad Rudolph (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008), 86-105, at 87. For an engaging analysis of Latino comic book narrative from the perspective of cognitive science, see Frederick Luis Aldama, Your Brain on Latino Comics. From Gus Arriola to Los Bros Hernandez (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009). According to Lewis, art historian E. H. Gombrich also played a crucial role in developing new theories of pictorial narrative: “. . . it was his probing of the spectator’s cognitive apparatus that enabled us to link narrative meaning and interpretation within a framework of cognitive psychology and cultural conditioning. Once the viewer entered the equation of narrator, story, and receptor, our theoretical understanding of pictorial narrative could be opened to a wider problematic and range of possibilities.” Lewis, 87. Lewis’s note to this passage cites the work of the art historian Karl Clausberg on a medieval German manuscript. Karl Clausberg, “Der Erfurter Codex Aureus, oder: Die Sprache der Bilder,” Städel-Jahrbuch n.f. 8 (1981), 22-56. Clausberg’s work on two manuscripts with banderoles, one of them the illustrated copy of Wernher’s poem, is even more relevant here. In describing what makes these manuscripts unusual, he speaks of “the virtually epidemical appearance of banderoles, which mix in everywhere in the representation of communication and discharge of emotion.” Karl Clausberg, “Spruchbandaussagen zum Stilcharakter—Malende und gemalte Gebärden, direkte und indirekte Rede in den Bildern der Veldeke-Aneide sowie Wernhers Marienliedern,” Städel-Jahrbuch N.F. 13 (1991), 81-110, at 81. His analysis of Wernher’s Maria engages the work of Wilhelm Messerer, who studied the miniatures in the Cracow manuscript from the perspective of word and image interaction, beginning with “the language of the banderoles.” Messerer, 448. Messerer’s perceptive readings focus on the banderoles as forms that convey meaning by rising or falling, wrapping around or passing above a figure or crossing or turning back from the frame. After analyses of other visual elements, such as gestures, drapery, and relationship between figure and frame, he concludes that all of these elements, which do not exist in text, “speak ‘parallel’ to text—admittedly with their own modifications, the way that in polyphonic music a second voice can behave toward the first.” Ibid., 471. It is important to Messerer that the elements he describes in the miniatures form parts of a “language”; he uses the analogy of translation to justify speaking of “the image as a certain equivalent of text, and thereby as language in the full sense” (447).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Emerging disciplines: shaping new fields of scholarly inquiry in and beyond the humanities' conversation and receive update notifications?