| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Our auditory system converts pressure waves into meaningful sounds. This translates into our ability to hear the sounds of nature, to appreciate the beauty of music, and to communicate with one another through spoken language. This section will provide an overview of the basic anatomy and function of the auditory system. It will include a discussion of how the sensory stimulus is translated into neural impulses, where in the brain that information is processed, how we perceive pitch, and how we know where sound is coming from.

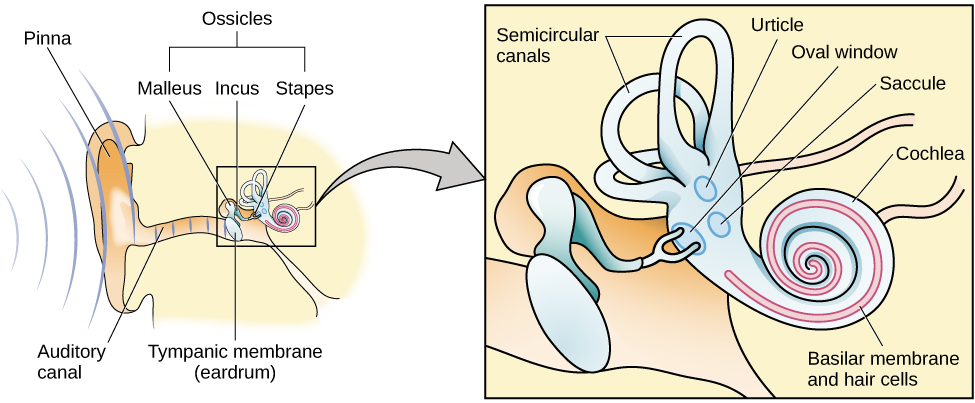

The ear can be separated into multiple sections. The outer ear includes the pinna , which is the visible part of the ear that protrudes from our heads, the auditory canal, and the tympanic membrane , or eardrum. The middle ear contains three tiny bones known as the ossicles , which are named the malleus (or hammer), incus (or anvil), and the stapes (or stirrup). The inner ear contains the semi-circular canals, which are involved in balance and movement (the vestibular sense), and the cochlea. The cochlea is a fluid-filled, snail-shaped structure that contains the sensory receptor cells (hair cells) of the auditory system ( [link] ).

Sound waves travel along the auditory canal and strike the tympanic membrane, causing it to vibrate. This vibration results in movement of the three ossicles. As the ossicles move, the stapes presses into a thin membrane of the cochlea known as the oval window. As the stapes presses into the oval window, the fluid inside the cochlea begins to move, which in turn stimulates hair cells , which are auditory receptor cells of the inner ear embedded in the basilar membrane. The basilar membrane is a thin strip of tissue within the cochlea.

The activation of hair cells is a mechanical process: the stimulation of the hair cell ultimately leads to activation of the cell. As hair cells become activated, they generate neural impulses that travel along the auditory nerve to the brain. Auditory information is shuttled to the inferior colliculus, the medial geniculate nucleus of the thalamus, and finally to the auditory cortex in the temporal lobe of the brain for processing. Like the visual system, there is also evidence suggesting that information about auditory recognition and localization is processed in parallel streams (Rauschecker&Tian, 2000; Renier et al., 2009).

Different frequencies of sound waves are associated with differences in our perception of the pitch of those sounds. Low-frequency sounds are lower pitched, and high-frequency sounds are higher pitched. How does the auditory system differentiate among various pitches?

Several theories have been proposed to account for pitch perception. We’ll discuss two of them here: temporal theory and place theory. The temporal theory of pitch perception asserts that frequency is coded by the activity level of a sensory neuron. This would mean that a given hair cell would fire action potentials related to the frequency of the sound wave. While this is a very intuitive explanation, we detect such a broad range of frequencies (20–20,000 Hz) that the frequency of action potentials fired by hair cells cannot account for the entire range. Because of properties related to sodium channels on the neuronal membrane that are involved in action potentials, there is a point at which a cell cannot fire any faster (Shamma, 2001).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Chapter 5: sensation and perception sw' conversation and receive update notifications?