| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

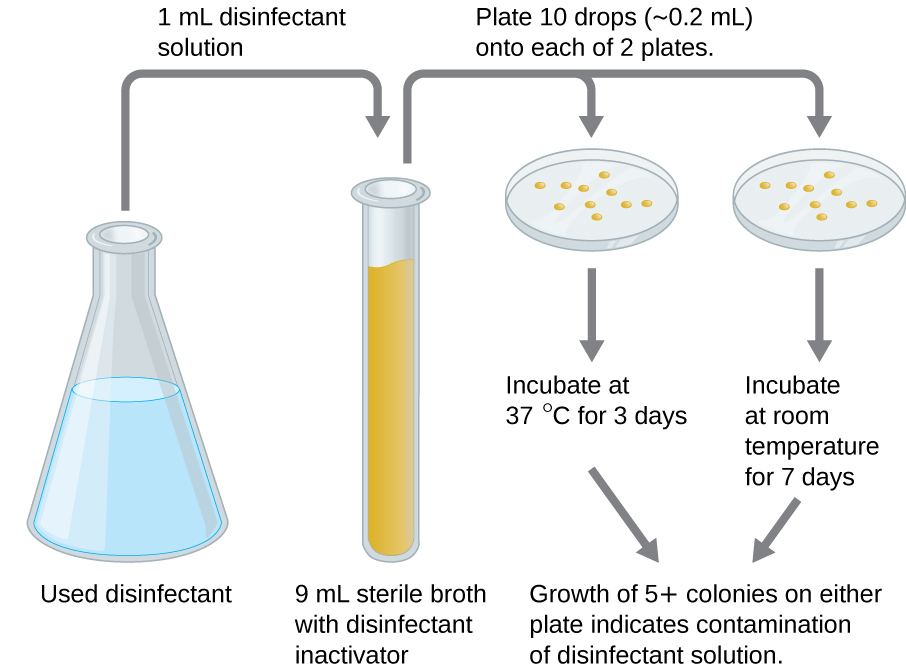

An in-use test can determine whether an actively used solution of disinfectant in a clinical setting is microbially contaminated ( [link] ). A 1-mL sample of the used disinfectant is diluted into 9 mL of sterile broth medium that also contains a compound to inactivate the disinfectant. Ten drops, totaling approximately 0.2 mL of this mixture, are then inoculated onto each of two agar plates. One plate is incubated at 37 °C for 3 days and the other is incubated at room temperature for 7 days. The plates are monitored for growth of microbial colonies. Growth of five or more colonies on either plate suggests that viable microbial cells existed in the disinfectant solution and that it is contaminated. Such in-use tests monitor the effectiveness of disinfectants in the clinical setting.

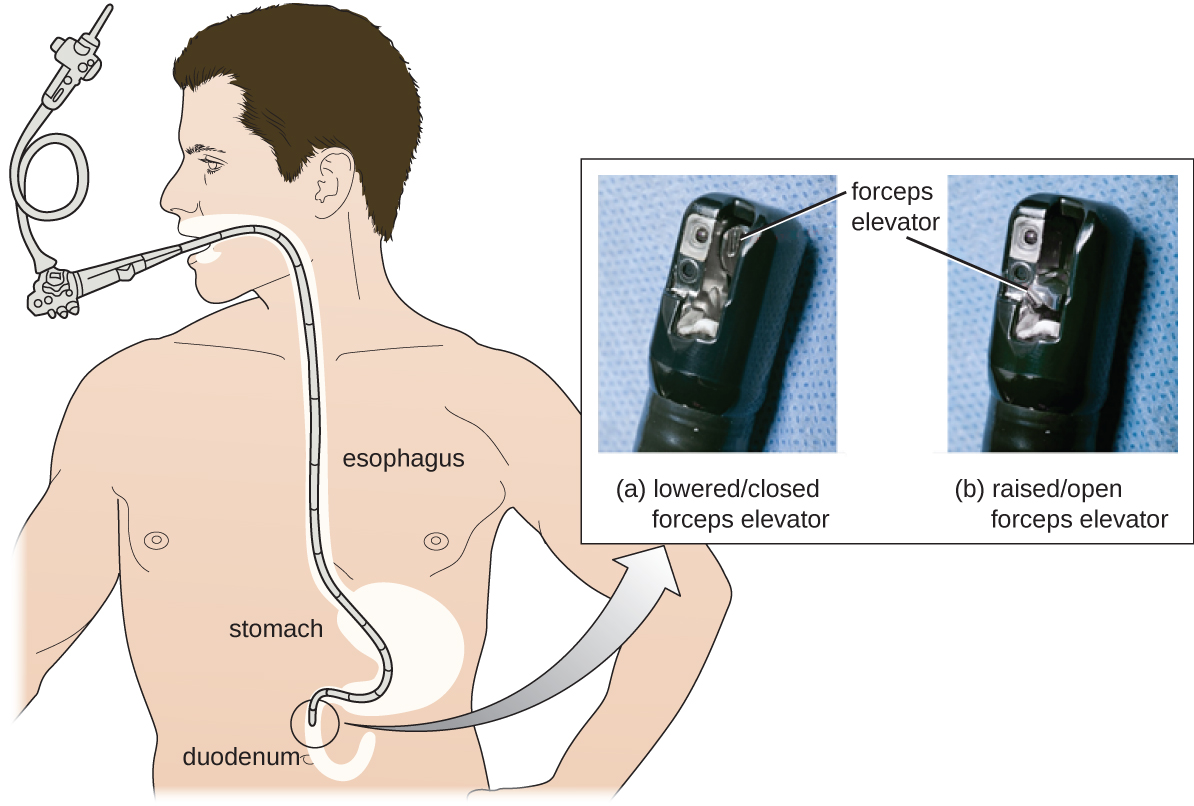

Despite antibiotic treatment, Roberta’s symptoms worsened. She developed pyelonephritis , a severe kidney infection, and was rehospitalized in the intensive care unit (ICU). Her condition continued to deteriorate, and she developed symptoms of septic shock . At this point, her physician ordered a culture from her urine to determine the exact cause of her infection, as well as a drug sensitivity test to determine what antibiotics would be effective against the causative bacterium. The results of this test indicated resistance to a wide range of antibiotics, including the carbapenems, a class of antibiotics that are used as the last resort for many types of bacterial infections. This was an alarming outcome, suggesting that Roberta’s infection was caused by a so-called superbug : a bacterial strain that has developed resistance to the majority of commonly used antibiotics. In this case, the causative agent belonged to the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) , a drug-resistant family of bacteria normally found in the digestive system ( [link] ). When CRE is introduced to other body systems, as might occur through improperly cleaned surgical instruments, catheters, or endoscopes, aggressive infections can occur.

CRE infections are notoriously difficult to treat, with a 40%–50% fatality rate. To treat her kidney infection and septic shock, Roberta was treated with dialysis, intravenous fluids, and medications to maintain blood pressure and prevent blood clotting. She was also started on aggressive treatment with intravenous administration of a new drug called tigecycline , which has been successful in treating infections caused by drug-resistant bacteria.

After several weeks in the ICU, Roberta recovered from her CRE infection. However, public health officials soon noticed that Roberta’s case was not isolated. Several patients who underwent similar procedures at the same hospital also developed CRE infections, some dying as a result. Ultimately, the source of the infection was traced to the duodenoscopes used in the procedures. Despite the hospital staff meticulously following manufacturer protocols for disinfection, bacteria, including CRE, remained within the instruments and were introduced to patients during procedures.

Go back to the previous Clinical Focus box.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections due to contaminated endoscopes have become a high-profile problem in recent years. Several CRE outbreaks have been traced to endoscopes, including a case at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in early 2015 in which 179 patients may have been exposed to a contaminated endoscope. Seven of the patients developed infections, and two later died. Several lawsuits have been filed against Olympus, the manufacturer of the endoscopes. Some claim that Olympus did not obtain FDA approval for design changes that may have led to contamination, and others claim that the manufacturer knowingly withheld information from hospitals concerning defects in the endoscopes.

Lawsuits like these raise difficult-to-answer questions about liability. Invasive procedures are inherently risky, but negative outcomes can be minimized by strict adherence to established protocols. Who is responsible, however, when negative outcomes occur due to flawed protocols or faulty equipment? Can hospitals or health-care workers be held liable if they have strictly followed a flawed procedure? Should manufacturers be held liable—and perhaps be driven out of business—if their lifesaving equipment fails or is found defective? What is the government’s role in ensuring that use and maintenance of medical equipment and protocols are fail-safe?

Protocols for cleaning or sterilizing medical equipment are often developed by government agencies like the FDA, and other groups, like the AOAC, a nonprofit scientific organization that establishes many protocols for standard use globally. These procedures and protocols are then adopted by medical device and equipment manufacturers. Ultimately, the end-users (hospitals and their staff) are responsible for following these procedures and can be held liable if a breach occurs and patients become ill from improperly cleaned equipment.

Unfortunately, protocols are not infallible, and sometimes it takes negative outcomes to reveal their flaws. In 2008, the FDA had approved a disinfection protocol for endoscopes, using glutaraldehyde (at a lower concentration when mixed with phenol), o-phthalaldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, peracetic acid, and a mix of hydrogen peroxide with peracetic acid. However, subsequent CRE outbreaks from endoscope use showed that this protocol alone was inadequate.

As a result of CRE outbreaks, hospitals, manufacturers, and the FDA are investigating solutions. Many hospitals are instituting more rigorous cleaning procedures than those mandated by the FDA. Manufacturers are looking for ways to redesign duodenoscopes to minimize hard-to-reach crevices where bacteria can escape disinfectants, and the FDA is updating its protocols. In February 2015, the FDA added new recommendations for careful hand cleaning of the duodenoscope elevator mechanism (the location where microbes are most likely to escape disinfection), and issued more careful documentation about quality control of disinfection protocols ( [link] ).

There is no guarantee that new procedures, protocols, or equipment will completely eliminate the risk for infection associated with endoscopes. Yet these devices are used successfully in 500,000–650,000 procedures annually in the United States, many of them lifesaving. At what point do the risks outweigh the benefits of these devices, and who should be held responsible when negative outcomes occur?

If a chemical disinfectant is more effective than phenol, then its phenol coefficient would be ________ than 1.0.

greater

If used for extended periods of time, ________ germicides may lead to sterility.

high-level

In the disk-diffusion assay, a large zone of inhibition around a disk to which a chemical disinfectant has been applied indicates ________ of the test microbe to the chemical disinfectant.

susceptibility or sensitivity

Why were chemical disinfectants once commonly compared with phenol?

Why is length of exposure to a chemical disinfectant important for its activity?

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?