| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

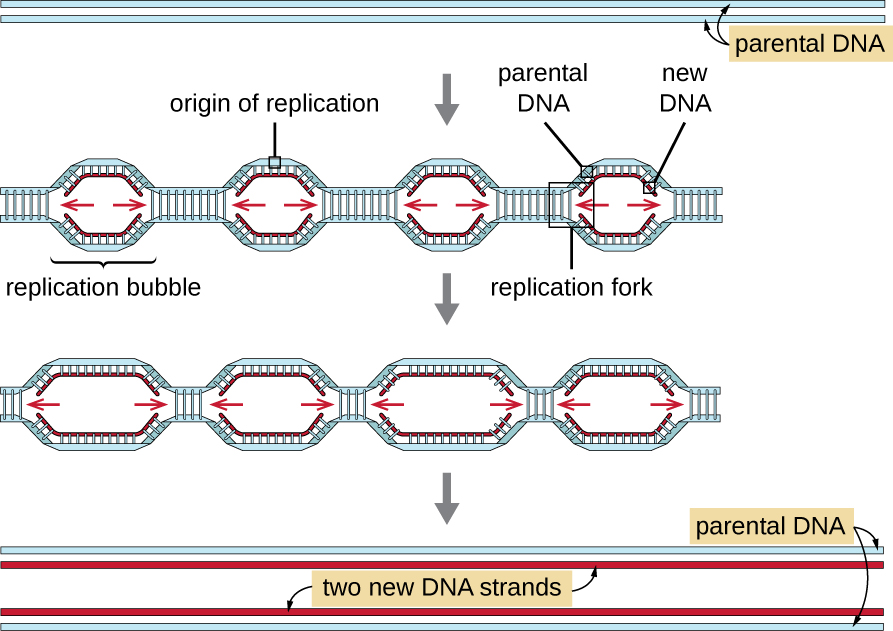

Eukaryotic genomes are much more complex and larger than prokaryotic genomes and are typically composed of multiple linear chromosomes ( [link] ). The human genome , for example, has 3 billion base pairs per haploid set of chromosomes, and 6 billion base pairs are inserted during replication. There are multiple origins of replication on each eukaryotic chromosome ( [link] ); the human genome has 30,000 to 50,000 origins of replication. The rate of replication is approximately 100 nucleotides per second—10 times slower than prokaryotic replication.

The essential steps of replication in eukaryotes are the same as in prokaryotes. Before replication can start, the DNA has to be made available as a template. Eukaryotic DNA is highly supercoiled and packaged, which is facilitated by many proteins, including histone s (see Structure and Function of Cellular Genomes ). At the origin of replication , a prereplication complex composed of several proteins, including helicase , forms and recruits other enzymes involved in the initiation of replication, including topoisomerase to relax supercoiling, single-stranded binding protein, RNA primase , and DNA polymerase . Following initiation of replication, in a process similar to that found in prokaryotes, elongation is facilitated by eukaryotic DNA polymerases. The leading strand is continuously synthesized by the eukaryotic polymerase enzyme pol δ, while the lagging strand is synthesized by pol ε. A sliding clamp protein holds the DNA polymerase in place so that it does not fall off the DNA. The enzyme ribonuclease H ( RNase H ), instead of a DNA polymerase as in bacteria, removes the RNA primer, which is then replaced with DNA nucleotides. The gaps that remain are sealed by DNA ligase .

Because eukaryotic chromosomes are linear, one might expect that their replication would be more straightforward. As in prokaryotes, the eukaryotic DNA polymerase can add nucleotides only in the 5’ to 3’ direction. In the leading strand, synthesis continues until it reaches either the end of the chromosome or another replication fork progressing in the opposite direction. On the lagging strand, DNA is synthesized in short stretches, each of which is initiated by a separate primer. When the replication fork reaches the end of the linear chromosome, there is no place to make a primer for the DNA fragment to be copied at the end of the chromosome. These ends thus remain unpaired and, over time, they may get progressively shorter as cells continue to divide.

The ends of the linear chromosomes are known as telomere s and consist of noncoding repetitive sequences. The telomeres protect coding sequences from being lost as cells continue to divide. In humans, a six base-pair sequence, TTAGGG, is repeated 100 to 1000 times to form the telomere. The discovery of the enzyme telomerase ( [link] ) clarified our understanding of how chromosome ends are maintained. Telomerase contains a catalytic part and a built-in RNA template. It attaches to the end of the chromosome, and complementary bases to the RNA template are added on the 3’ end of the DNA strand. Once the 3’ end of the lagging strand template is sufficiently elongated, DNA polymerase can add the nucleotides complementary to the ends of the chromosomes. In this way, the ends of the chromosomes are replicated. In humans, telomerase is typically active in germ cells and adult stem cells; it is not active in adult somatic cells and may be associated with the aging of these cells. Eukaryotic microbes including fungi and protozoans also produce telomerase to maintain chromosomal integrity. For her discovery of telomerase and its action, Elizabeth Blackburn (1948–) received the Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology in 2009.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?