| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Maria, a 20-year-old anthropology student from Texas, recently became ill in the African nation of Botswana, where she was conducting research as part of a study-abroad program. Maria’s research was focused on traditional African methods of tanning hides for the production of leather. Over a period of three weeks, she visited a tannery daily for several hours to observe and participate in the tanning process. One day, after returning from the tannery, Maria developed a fever, chills, and a headache, along with chest pain, muscle aches, nausea, and other flu-like symptoms. Initially, she was not concerned, but when her fever spiked and she began to cough up blood, her African host family became alarmed and rushed her to the hospital, where her condition continued to worsen.

After learning about her recent work at the tannery, the physician suspected that Maria had been exposed to anthrax . He ordered a chest X-ray, a blood sample, and a spinal tap, and immediately started her on a course of intravenous penicillin. Unfortunately, lab tests confirmed the physician’s presumptive diagnosis. Maria’s chest X-ray exhibited pleural effusion, the accumulation of fluid in the space between the pleural membranes, and a Gram stain of her blood revealed the presence of gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria in short chains, consistent with Bacillus anthracis . Blood and bacteria were also shown to be present in her cerebrospinal fluid, indicating that the infection had progressed to meningitis. Despite supportive treatment and aggressive antibiotic therapy, Maria slipped into an unresponsive state and died three days later.

Anthrax is a disease caused by the introduction of endospores from the gram-positive bacterium B. anthracis into the body. Once infected, patients typically develop meningitis, often with fatal results. In Maria’s case, she inhaled the endospores while handling the hides of animals that had been infected.

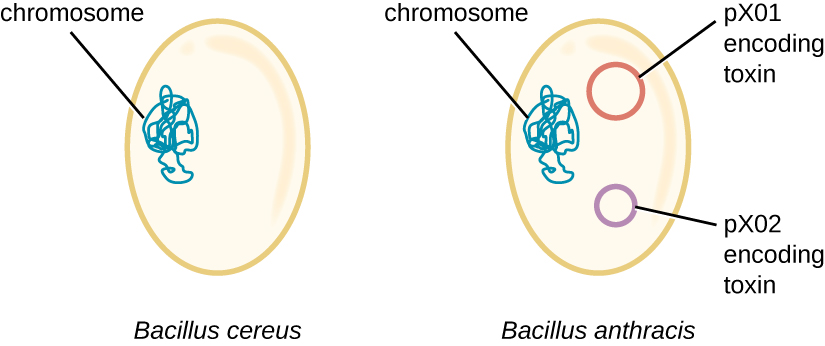

The genome of B. anthracis illustrates how small structural differences can lead to major differences in virulence. In 2003, the genomes of B. anthracis and Bacillus cereus , a similar but less pathogenic bacterium of the same genus, were sequenced and compared. N. Ivanova et al. “Genome Sequence of Bacillus cereus and Comparative Analysis with Bacillus anthracis.” Nature 423 no. 6935 (2003):87–91. Researchers discovered that the 16S rRNA gene sequences of these bacteria are more than 99% identical, meaning that they are actually members of the same species despite their traditional classification as separate species. Although their chromosomal sequences also revealed a great deal of similarity, several virulence factors of B. anthracis were found to be encoded on two large plasmids not found in B. cereus . The plasmid pX01 encodes a three-part toxin that suppresses the host immune system, whereas the plasmid pX02 encodes a capsular polysaccharide that further protects the bacterium from the host immune system ( [link] ). Since B. cereus lacks these plasmids, it does not produce these virulence factors, and although it is still pathogenic, it is typically associated with mild cases of diarrhea from which the body can quickly recover. Unfortunately for Maria, the presence of these toxin-encoding plasmids in B. anthracis gives it its lethal virulence.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Microbiology' conversation and receive update notifications?