| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

When the United States eliminates trade barriers in one area, consumers spend the money they save on that product elsewhere in the economy—so there is no overall loss of jobs for the economy as a whole. Of course, workers in some of the poorest countries of the world who would otherwise have jobs producing textiles, would gain considerably if the United States reduced its barriers to trade in textiles. That said, there are good reasons to be wary about reducing barriers to trade. The 2012 and 2013 Bangladeshi fires in textile factories, which resulted in a horrific loss of life, present complications that our simplified analysis in the chapter will not capture.

Realizing the compromises between nations that come about due to trade policy, many countries came together in 1947 to form the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). (We’ll cover the GATT in more detail later in the chapter.) This agreement has since been superseded by the World Trade Organization (WTO) , whose membership includes about 150 nations and most of the economies of the world. It is the primary international mechanism through which nations negotiate their trade rules—including rules about tariffs, quotas, and nontariff barriers. The next section examines the results of such protectionism and develops a simple model to show the impact of trade policy.

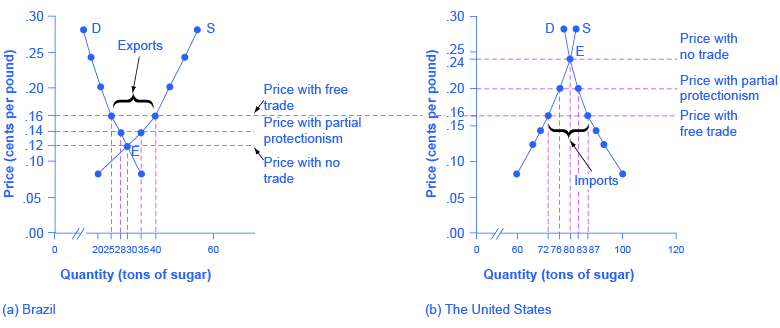

To the non-economist, restricting imports may appear to be nothing more than taking sales from foreign producers and giving them to domestic producers. Other factors are at work, however, because firms do not operate in a vacuum. Instead, firms sell their products either to consumers or to other firms (if they are business suppliers), who are also affected by the trade barriers. A demand and supply analysis of protectionism shows that it is not just a matter of domestic gains and foreign losses, but a policy that imposes substantial domestic costs as well.

Consider two countries, Brazil and the United States, who produce sugar. Each country has a domestic supply and demand for sugar, as detailed in [link] and illustrated in [link] . In Brazil, without trade, the equilibrium price of sugar is 12 cents per pound and the equilibrium output is 30 tons. When there is no trade in the United States, the equilibrium price of sugar is 24 cents per pound and the equilibrium quantity is 80 tons. These equilibrium points are labeled with the point E.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Macroeconomics' conversation and receive update notifications?