| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Hannah Ingraham was eleven years old in 1783, when her Loyalist family removed from New York to Ste. Anne’s Point in the colony of Nova Scotia. Later in life, she compiled her memories of that time.

[Father] said we were to go to Nova Scotia, that a ship was ready to take us there, so we made all haste to get ready. . . . Then on Tuesday, suddenly the house was surrounded by rebels and father was taken prisoner and carried away. . . . When morning came, they said he was free to go.

We had five wagon loads carried down the Hudson in a sloop and then we went on board the transport that was to bring us to Saint John. I was just eleven years old when we left our farm to come here. It was the last transport of the season and had on board all those who could not come sooner. The first transports had come in May so the people had all the summer before them to get settled. . . .

We lived in a tent at St. Anne’s until father got a house ready. . . . There was no floor laid, no windows, no chimney, no door, but we had a roof at least. A good fire was blazing and mother had a big loaf of bread and she boiled a kettle of water and put a good piece of butter in a pewter bowl. We toasted the bread and all sat around the bowl and ate our breakfast that morning and mother said: “Thank God we are no longer in dread of having shots fired through our house. This is the sweetest meal I ever tasted for many a day.”

What do these excerpts tell you about life as a Loyalist in New York or as a transplant to Canada?

While some slaves who fought for the Patriot cause received their freedom, revolutionary leaders—unlike the British—did not grant such slaves their freedom as a matter of course. Washington, the owner of more than two hundred slaves during the Revolution, refused to let slaves serve in the army, although he did allow free blacks. (In his will, Washington did free his slaves.) In the new United States, the Revolution largely reinforced a racial identity based on skin color. Whiteness, now a national identity, denoted freedom and stood as the key to power. Blackness, more than ever before, denoted servile status. Indeed, despite their class and ethnic differences, white revolutionaries stood mostly united in their hostility to both blacks and Indians.

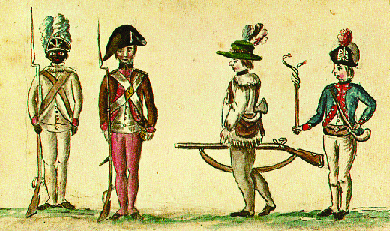

In the Revolutionary War, some blacks, both free and enslaved, chose to fight for the Americans ( [link] ). Others chose to fight for the British, who offered them freedom for joining their cause. Read the excerpts below for the perspective of a black veteran from each side of the conflict.

Boyrereau Brinch was captured in Africa at age sixteen and brought to America as a slave. He joined the Patriot forces and was honorably discharged and emancipated after the war. He told his story to Benjamin Prentiss, who published it as The Blind African Slave in 1810.

Finally, I was in the battles at Cambridge, White Plains, Monmouth, Princeton, Newark, Frog’s Point, Horseneck where I had a ball pass through my knapsack. All which battels [sic] the reader can obtain a more perfect account of in history, than I can give. At last we returned to West Point and were discharged [1783], as the war was over. Thus was I, a slave for five years fighting for liberty. After we were disbanded, I returned to my old master at Woodbury [Connecticut], with whom I lived one year, my services in the American war, having emancipated me from further slavery, and from being bartered or sold. . . . Here I enjoyed the pleasures of a freeman; my food was sweet, my labor pleasure: and one bright gleam of life seemed to shine upon me.

Boston King was a Charleston-born slave who escaped his master and joined the Loyalists. He made his way to Nova Scotia and later Sierra Leone, where he published his memoirs in 1792. The excerpt below describes his experience in New York after the war.

When I arrived at New-York, my friends rejoiced to see me once more restored to liberty, and joined me in praising the Lord for his mercy and goodness. . . . [In 1783] the horrors and devastation of war happily terminated, and peace was restored between America and Great Britain, which diffused universal joy among all parties, except us, who had escaped from slavery and taken refuge in the English army; for a report prevailed at New-York, that all the slaves, in number 2000, were to be delivered up to their masters, altho’ some of them had been three or four years among the English. This dreadful rumour filled us all with inexpressible anguish and terror, especially when we saw our old masters coming from Virginia, North-Carolina, and other parts, and seizing upon their slaves in the streets of New-York, or even dragging them out of their beds. Many of the slaves had very cruel masters, so that the thoughts of returning home with them embittered life to us. For some days we lost our appetite for food, and sleep departed from our eyes. The English had compassion upon us in the day of distress, and issued out a Proclamation, importing, That all slaves should be free, who had taken refuge in the British lines, and claimed the sanction and privileges of the Proclamations respecting the security and protection of Negroes. In consequence of this, each of us received a certificate from the commanding officer at New-York, which dispelled all our fears, and filled us with joy and gratitude.

What do these two narratives have in common, and how are they different? How do the two men describe freedom?

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?