| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Browse through the cartoons and commentary at 1896 at Vassar College, a site that contains a wealth of information about the major players and themes of the presidential election of 1896.

As the Populist convention unfolded, the delegates had an important decision to make: either locate another candidate, even though Bryan would have been an excellent choice, or join the Democrats and support Bryan as the best candidate but risk losing their identity as a third political party as a result. The Populist Party chose the latter and endorsed Bryan’s candidacy. However, they also nominated their own vice-presidential candidate, Georgia Senator Tom Watson, as opposed to the Democratic nominee, Arthur Sewall, presumably in an attempt to maintain some semblance of a separate identity.

The race was a heated one, with McKinley running a typical nineteenth-century style “front porch” campaign, during which he espoused the long-held Republican Party principles to visitors who would call on him at his Ohio home. Bryan, to the contrary, delivered speeches all throughout the country, bringing his message to the people that Republicans “shall not crucify mankind on a cross of gold.”

William Jennings Bryan was a politician and speechmaker in the late nineteenth century, and he was particularly well known for his impassioned argument that the country move to a bimetal or silver standard. He received the Democratic presidential nomination in 1896, and, at the nominating convention, he gave his most famous speech. He sought to argue against Republicans who stated that the gold standard was the only way to ensure stability and prosperity for American businesses. In the speech he said:

We say to you that you have made the definition of a business man too limited in its application. The man who is employed for wages is as much a business man as his employer; the attorney in a country town is as much a business man as the corporation counsel in a great metropolis; the merchant at the cross-roads store is as much a business man as the merchant of New York; the farmer who goes forth in the morning and toils all day, who begins in spring and toils all summer, and who by the application of brain and muscle to the natural resources of the country creates wealth, is as much a business man as the man who goes upon the Board of Trade and bets upon the price of grain; . . . We come to speak of this broader class of business men.

This defense of working Americans as critical to the prosperity of the country resonated with his listeners, as did his passionate ending when he stated, “Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests, and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: ‘You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.’”

The speech was an enormous success and played a role in convincing the Populist Party that he was the candidate for them.

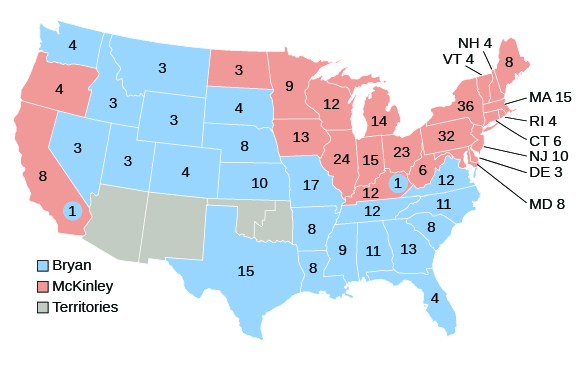

The result was a close election that finally saw a U.S. president win a majority of the popular vote for the first time in twenty-four years. McKinley defeated Bryan by a popular vote of 7.1 million to 6.5 million. Bryan’s showing was impressive by any standard, as his popular vote total exceeded that of any other presidential candidate in American history to that date—winner or loser. He polled nearly one million more votes than did the previous Democratic victor, Grover Cleveland; however, his campaign also served to split the Democratic vote, as some party members remained convinced of the propriety of the gold standard and supported McKinley in the election.

Amid a growing national depression where Americans truly recognized the importance of a strong leader with sound economic policies, McKinley garnered nearly two million more votes than his Republican predecessor Benjamin Harrison. Put simply, the American electorate was energized to elect a strong candidate who could adequately address the country’s economic woes. Voter turnout was the largest in American history to that date; while both candidates benefitted, McKinley did more so than Bryan ( [link] ).

In the aftermath, it is easy to say that it was Bryan’s defeat that all but ended the rise of the Populist Party. Populists had thrown their support to the Democrats who shared similar ideas for the economic rebound of the country and lost. In choosing principle over distinct party identity, the Populists aligned themselves to the growing two-party American political system and would have difficulty maintaining party autonomy afterwards. Future efforts to establish a separate party identity would be met with ridicule by critics who would say that Populists were merely “Democrats in sheep’s clothing.”

But other factors also contributed to the decline of Populism at the close of the century. First, the discovery of vast gold deposits in Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896–1899 (also known as the “Yukon Gold Rush”) shored up the nation’s weakening economy and made it possible to thrive on a gold standard. Second, the impending Spanish-American War, which began in 1898, further fueled the economy and increased demand for American farm products. Still, the Populist spirit remained, although it lost some momentum at the close of the nineteenth century. As will be seen in a subsequent chapter, the reformist zeal took on new forms as the twentieth century unfolded.

As the economy worsened, more Americans suffered; as the federal government continued to offer few solutions, the Populist movement began to grow. Populist groups approached the 1896 election anticipating that the mass of struggling Americans would support their movement for change. When Democrats chose William Jennings Bryan for their candidate, however, they chose a politician who largely fit the mold of the Populist platform—from his birthplace of Nebraska to his advocacy of the silver standard that most farmers desired. Throwing their support behind Bryan as well, Populists hoped to see a candidate in the White House who would embody the Populist goals, if not the party name. When Bryan lost to Republican William McKinley, the Populist Party lost much of its momentum. As the country climbed out of the depression, the interest in a third party faded away, although the reformist movement remained intact.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?