| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

As world leaders debated the terms of the peace, the American public faced its own challenges at the conclusion of the First World War. Several unrelated factors intersected to create a chaotic and difficult time, just as massive numbers of troops rapidly demobilized and came home. Racial tensions, a terrifying flu epidemic, anticommunist hysteria, and economic uncertainty all combined to leave many Americans wondering what, exactly, they had won in the war. Adding to these problems was the absence of President Wilson, who remained in Paris for six months, leaving the country leaderless. The result of these factors was that, rather than a celebratory transition from wartime to peace and prosperity, and ultimately the Jazz Age of the 1920s, 1919 was a tumultuous year that threatened to tear the country apart.

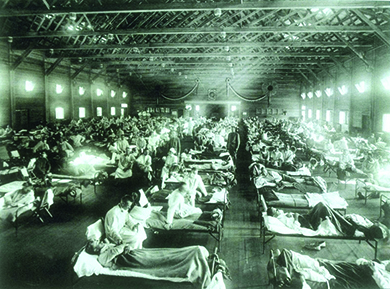

After the war ended, U.S. troops were demobilized and rapidly sent home. One unanticipated and unwanted effect of their return was the emergence of a new strain of influenza that medical professionals had never before encountered. Within months of the war’s end, over twenty million Americans fell ill from the flu ( [link] ). Eventually, 675,000 Americans died before the disease mysteriously ran its course in the spring of 1919. Worldwide, recent estimates suggest that 500 million people suffered from this flu strain, with as many as fifty million people dying. Throughout the United States, from the fall of 1918 to the spring of 1919, fear of the flu gripped the country. Americans avoided public gatherings, children wore surgical masks to school, and undertakers ran out of coffins and burial plots in cemeteries. Hysteria grew as well, and instead of welcoming soldiers home with a postwar celebration, people hunkered down and hoped to avoid contagion.

Another element that greatly influenced the challenges of immediate postwar life was economic upheaval. As discussed above, wartime production had led to steady inflation; the rising cost of living meant that few Americans could comfortably afford to live off their wages. When the government’s wartime control over the economy ended, businesses slowly recalibrated from the wartime production of guns and ships to the peacetime production of toasters and cars. Public demand quickly outpaced the slow production, leading to notable shortages of domestic goods. As a result, inflation skyrocketed in 1919. By the end of the year, the cost of living in the United States was nearly double what it had been in 1916. Workers, facing a shortage in wages to buy more expensive goods, and no longer bound by the no-strike pledge they made for the National War Labor Board, initiated a series of strikes for better hours and wages. In 1919 alone, more than four million workers participated in a total of nearly three thousand strikes: both records within all of American history.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?