| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Finally, Elazar argues that in individualistic states, electoral competition does not seek to identify the candidate with the best ideas. Instead it pits against each other political parties that are well organized and compete directly for votes. Voters are loyal to the candidates who hold the same party affiliation they do. As a result, unlike the case in moralistic cultures, voters do not pay much attention to the personalities of the candidates when deciding how to vote and are less tolerant of third-party candidates.

Given the prominence of slavery in its formation, a traditionalistic political culture , in Elazar’s argument, sees the government as necessary to maintaining the existing social order, the status quo. Only elites belong in the political enterprise, and as a result, new public policies will be advanced only if they reinforce the beliefs and interests of those in power.

Elazar associates traditionalistic political culture with the southern portion of the United States, where it developed in the upper regions of Virginia and Kentucky before spreading to the Deep South and the Southwest. Like the individualistic culture, the traditionalistic culture believes in the importance of the individual. But instead of profiting from corporate ventures, settlers in traditionalistic states tied their economic fortunes to the necessity of slavery on plantations throughout the South.

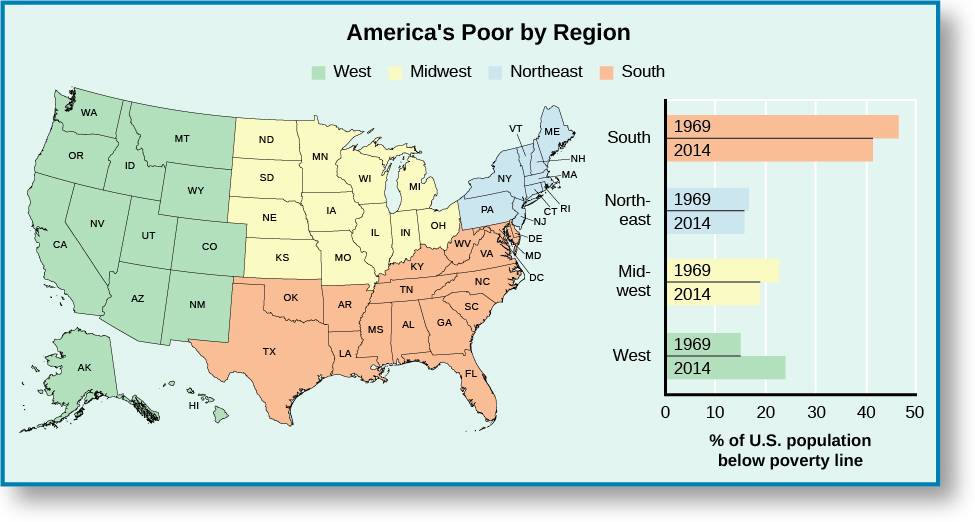

When elected officials do not prioritize public policies that benefit them, those on the social and economic fringes of society can be plagued by poverty and pervasive health problems. For example, although

[link] shows that poverty is a problem across the entire United States, the South has the highest incidence. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the South also leads the nation in self-reported obesity, closely followed by the Midwest.

While moralistic cultures expect and encourage political participation by all citizens, traditionalistic cultures are more likely to see it as a privilege reserved for only those who meet the qualifications. As a result, voter participation will generally be lower in a traditionalistic culture, and there will be more barriers to participation (e.g., a requirement to produce a photo ID at the voting booth). Conservatives argue that these laws reduce or eliminate fraud on the part of voters, while liberals believe they disproportionally disenfranchise the poor and minorities and constitute a modern-day poll tax.

Visit the National Conference of State Legislatures for an overview of Voter Identification Requirements by state.

Finally, under a traditionalistic political culture, Elazar argues that party competition will tend to occur between factions within a dominant party. Historically, the Democratic Party dominated the political structure in the South before realignment during the civil rights era. Today, depending on the office being sought, the parties are more likely to compete for voters.

Several critiques have come to light since

Elazar first introduced his theory of state political culture fifty years ago. The original theory rested on the assumption that new cultures could arise with the influx of settlers from different parts of the world; however, since immigration patterns have changed over time, it could be argued that the three cultures no longer match the country’s current reality. Today’s immigrants are less likely to come from European countries and are more likely to originate in Latin American and Asian countries.

It is also true that people migrate for more reasons than simple economics. They may be motivated by social issues such as widespread unemployment, urban decay, or low-quality health care of schools. Such trends may aggravate existing differences, for example the difference between urban and rural lifestyles (e.g., the city of Atlanta vs. other parts of Georgia), which are not accounted for in Elazar’s classification. Finally, unlike economic or demographic characteristics that lend themselves to more precise measurement, culture is a comprehensive concept that can be difficult to quantify. This can limit its explanatory power in political science research.

Daniel Elazar’s theory argues, based on the cultural values of early immigrants who settled in different regions of the country, the United States is made up of three component cultures: individualistic, moralistic, and traditionalistic. Each culture views aspects of government and politics differently, particularly the nature and purpose of political competition and the role of citizen participation. Critics of the theory say the arrival of recent immigrants from other parts of the globe, the divide between urban and rural lifestyles in a particular state, and new patterns of diffusion and settlement across states and regions mean the theory is no longer an entirely accurate description of reality.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'American government' conversation and receive update notifications?