| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Western composers often consistently choose minor keys over major keys (or vice versa) to convey certain moods (minor for melancholy, for example, and major for serene). One interesting aspect of Greek modes is that different modes were considered to have very different effects, not only on a person's mood, but even on character and morality. This may also be another clue that ancient modes may have had more variety of tuning and pitch than modern keys do.

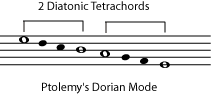

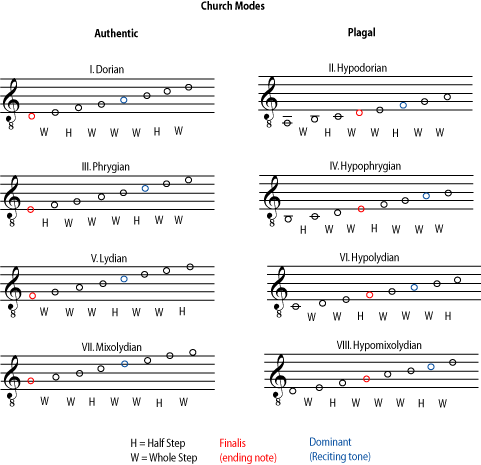

Sacred music in the middle ages in Western Europe - Gregorian chant, for example - was also modal, and the medieval church modes were also considered to have different effects on the listener. (As of this writing the site Ricercares by Vincenzo Galilei had a list of the "ethos" or mood associated with each medieval mode.) The names of the church modes were even borrowed from the names of the Greek modes, although the two systems don't really correspond to each other, or usemay have sounded more like some of the traditional raga-based Mediterranean and Middle Eastern musics (see below ) than like medieval Western-European church music, and to avoid confusion some people prefer to name the church modes using Roman numerals.

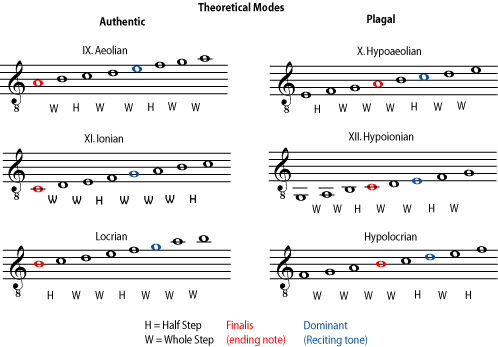

A mode can be found by playing all the "white key" notes on a piano for one octave. From D to D, for example is Dorian; from F to F is Lydian. Notice that no church modes began on A, B, or C. This is because a B flat was allowed, and the modes beginning on D, E, and F, when they use a B flat, have the same note patterns and relationships as would modes beginning on A, B, and C. After the middle ages, modes beginning on A, B, and C were named, but they are still not considered church modes. Notice that the Aeolian (or the Dorian using a B flat) is the same as an A (or D) natural minor scale and the Ionian (or the Lydian using a B flat) is the same as a C (or F) major scale.

Each of these modes can easily be found by playing its one octave range, or

ambitus , on the "white key" notes on a piano. But the Dorian mode, for example, didn't have to start on the pitch we call a D. The important thing was the pattern of half steps and whole steps within that octave, and their relationship to the notes that acted as the modal equivalent of

tonal centers , the

In our modern tonal system, any note may be sharp, flat, or natural , but in this modal system, only the B was allowed to vary. The symbols used to indicate whether the B was "hard" (our B natural) or "soft" (our B flat) eventually evolved into our symbols for sharps, flats, and naturals. All of this may seem very arbitrary, but it's important to remember that medieval mode theory, just like our modern music theory, was not trying to invent a logical system of music. It was trying to explain, describe, and systematize musical practices that were already flourishing because people liked the way they sounded.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Understanding basic music theory' conversation and receive update notifications?