| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

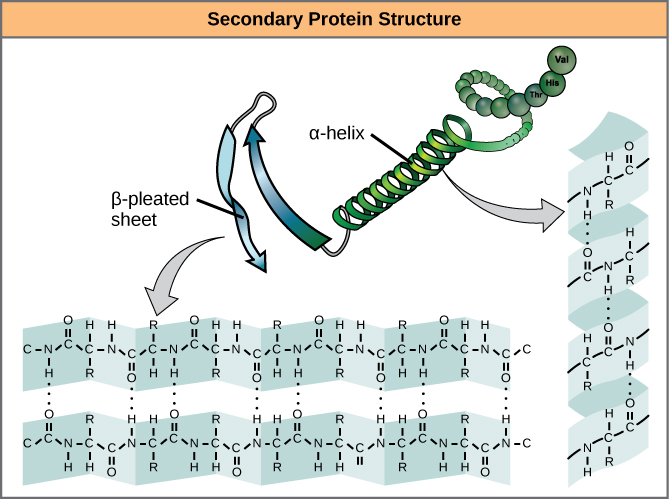

The local folding of the polypeptide in some regions gives rise to the secondary structure of the protein. The most common are the α -helix and β -pleated sheet structures ( [link] ). Both structures are the α -helix structure—the helix held in shape by hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bonds form between the oxygen atom in the carbonyl group in one amino acid and another amino acid that is four amino acids farther along the chain.

Every helical turn in an alpha helix has 3.6 amino acid residues. The R groups (the variant groups) of the polypeptide protrude out from the α -helix chain. In the β -pleated sheet, the “pleats” are formed by hydrogen bonding between atoms on the backbone of the polypeptide chain. The R groups are attached to the carbons and extend above and below the folds of the pleat. The pleated segments align parallel or antiparallel to each other, and hydrogen bonds form between the partially positive nitrogen atom in the amino group and the partially negative oxygen atom in the carbonyl group of the peptide backbone. The α -helix and β -pleated sheet structures are found in most globular and fibrous proteins and they play an important structural role.

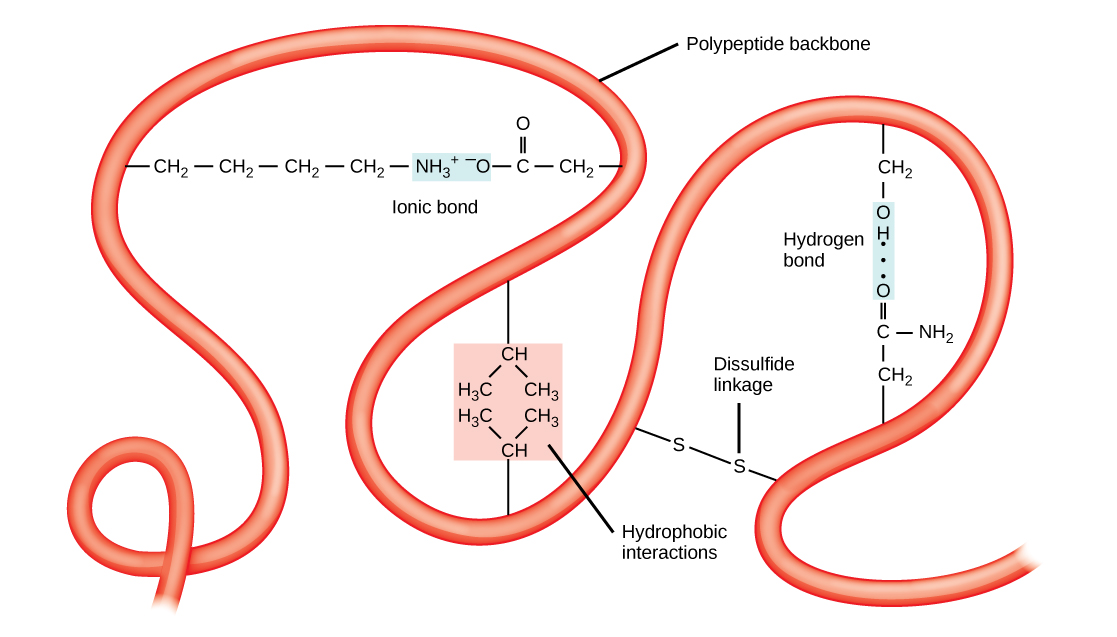

The unique three-dimensional structure of a polypeptide is its tertiary structure ( [link] ). This structure is in part due to chemical interactions at work on the polypeptide chain. Primarily, the interactions among R groups creates the complex three-dimensional tertiary structure of a protein. The nature of the R groups found in the amino acids involved can counteract the formation of the hydrogen bonds described for standard secondary structures. For example, R groups with like charges are repelled by each other and those with unlike charges are attracted to each other (ionic bonds). When protein folding takes place, the hydrophobic R groups of nonpolar amino acids lay in the interior of the protein, whereas the hydrophilic R groups lay on the outside. The former types of interactions are also known as hydrophobic interactions. Interaction between cysteine side chains forms disulfide linkages in the presence of oxygen, the only covalent bond forming during protein folding.

All of these interactions, weak and strong, determine the final three-dimensional shape of the protein. When a protein loses its three-dimensional shape, it may no longer be functional.

In nature, some proteins are formed from several polypeptides, also known as subunits, and the interaction of these subunits forms the quaternary structure . Weak interactions between the subunits help to stabilize the overall structure. For example, insulin (a globular protein) has a combination of hydrogen bonds and disulfide bonds that cause it to be mostly clumped into a ball shape. Insulin starts out as a single polypeptide and loses some internal sequences in the presence of post-translational modification after the formation of the disulfide linkages that hold the remaining chains together. Silk (a fibrous protein), however, has a β -pleated sheet structure that is the result of hydrogen bonding between different chains.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Biological macromolecules (gpc)' conversation and receive update notifications?