| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Mendel’s seminal work was accomplished using the garden pea, Pisum sativum , to study inheritance. This species naturally self-fertilizes, such that pollen encounters ova within individual flowers. The flower petals remain sealed tightly until after pollination, preventing pollination from other plants. The result is highly inbred, or “true-breeding,” pea plants. These are plants that always produce offspring that look like the parent. By experimenting with true-breeding pea plants, Mendel avoided the appearance of unexpected traits in offspring that might occur if the plants were not true breeding. The garden pea also grows to maturity within one season, meaning that several generations could be evaluated over a relatively short time. Finally, large quantities of garden peas could be cultivated simultaneously, allowing Mendel to conclude that his results did not come about simply by chance.

Mendel performed hybridizations , which involve mating two true-breeding individuals that have different traits. In the pea, which is naturally self-pollinating, this is done by manually transferring pollen from the anther of a mature pea plant of one variety to the stigma of a separate mature pea plant of the second variety. In plants, pollen carries the male gametes (sperm) to the stigma, a sticky organ that traps pollen and allows the sperm to move down the pistil to the female gametes (ova) below. To prevent the pea plant that was receiving pollen from self-fertilizing and confounding his results, Mendel painstakingly removed all of the anthers from the plant’s flowers before they had a chance to mature.

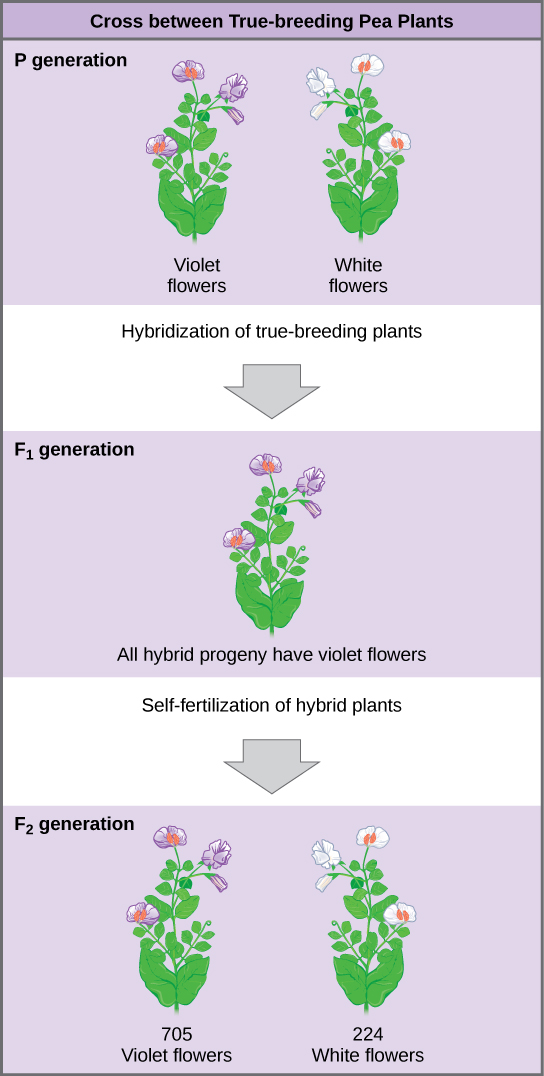

Plants used in first-generation crosses were called P 0 , or parental generation one, plants ( [link] ). Mendel collected the seeds belonging to the P 0 plants that resulted from each cross and grew them the following season. These offspring were called the F 1 , or the first filial ( filial = offspring, daughter or son), generation. Once Mendel examined the characteristics in the F 1 generation of plants, he allowed them to self-fertilize naturally. He then collected and grew the seeds from the F 1 plants to produce the F 2 , or second filial, generation. Mendel’s experiments extended beyond the F 2 generation to the F 3 and F 4 generations, and so on, but it was the ratio of characteristics in the P 0 −F 1 −F 2 generations that were the most intriguing and became the basis for Mendel’s postulates.

In his 1865 publication, Mendel reported the results of his crosses involving seven different characteristics, each with two contrasting traits. A trait is defined as a variation in the physical appearance of a heritable characteristic. The characteristics included plant height, seed texture, seed color, flower color, pea pod size, pea pod color, and flower position. For the characteristic of flower color, for example, the two contrasting traits were white versus violet. To fully examine each characteristic, Mendel generated large numbers of F 1 and F 2 plants, reporting results from 19,959 F 2 plants alone. His findings were consistent.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Mendelian genetics (gpc)' conversation and receive update notifications?