| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

A process which led from the amoeba to man appeared to the philosophers to be obviously a progress—though whether the amoeba would agree with this opinion is not known.Bertrand Russell, from "Current Tendencies", delivered as the first of a series of Lowell Lectures in Boston (Mar 1914).

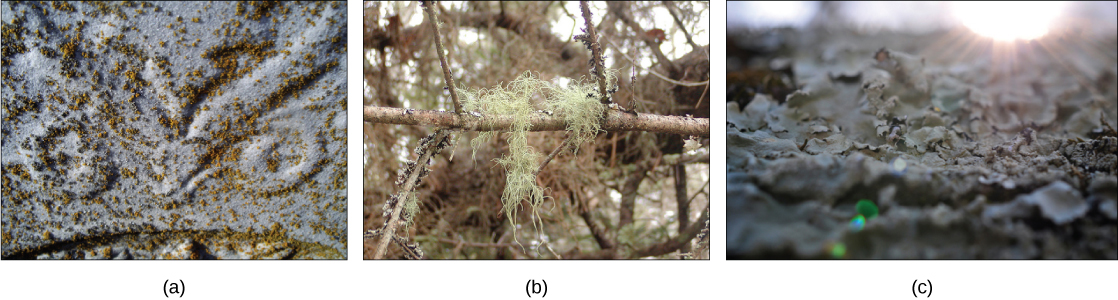

Lichens display a range of colors and textures ( [link] ) and can survive in the most unusual and hostile habitats. They cover rocks, gravestones, tree bark, and the ground in the tundra where plant roots cannot penetrate. Lichens can survive extended periods of drought, when they become completely desiccated, and then rapidly become active once water is available again.

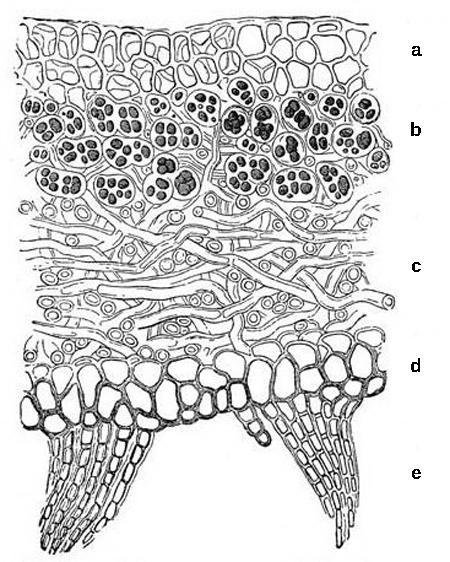

Lichens are an example of a mutualism, in which a fungus (usually a member of the Ascomycota or Basidiomycota phyla) lives in close contact with a photosynthetic organism (a eukaryotic alga or a prokaryotic cyanobacterium) ( [link] ). Generally, neither the fungus nor the photosynthetic organism can survive alone outside of the symbiotic relationship. The body of a lichen, referred to as a thallus, is formed of hyphae wrapped around the photosynthetic partner. The photosynthetic organism provides carbon and energy in the form of carbohydrates. Some cyanobacteria fix nitrogen from the atmosphere, contributing nitrogenous compounds to the association. In return, the fungus supplies minerals and protection from dryness and excessive light by encasing the algae in its mycelium. The fungus also attaches the symbiotic organism to the substrate.

Lichens grow very slowly, expanding a few millimeters per year. Both the fungus and the alga participate in the formation of dispersal units for reproduction. Lichens produce soredia, clusters of algal cells surrounded by mycelia. Soredia are dispersed by wind and water and form new lichens.

Lichens are extremely sensitive to air pollution, especially to abnormal levels of nitrogen and sulfur. The U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service can monitor air quality by measuring the relative abundance and health of the lichen population in an area. Lichens fulfill many ecological roles. Lichens are often early colonizers of bare rock. Caribou and reindeer eat lichens, and they provide cover for small invertebrates that hide in the mycelium. In the production of textiles, weavers used lichens to dye wool for many centuries until the advent of synthetic dyes.

Amoebae are just one of the creatures that are lumped into the Kingdom Protista, and amoebae and philosophers do share a common ancestor, as Russell points out. In the span of the last several decades, the Kingdom Protista has been disassembled and rearranged, as DNA sequence analyses have revealed new genetic (and therefore evolutionary) relationships among these eukaryotes. Moreover, protists species that exhibit similar morphological features may not be closely related, but may have evolved analogous structures because of similar selective pressures — rather than because of recent common ancestry. This phenomenon, called convergent evolution , is one reason why protist classification is so challenging. The emerging classification scheme groups the entire domain Eukarya into six “supergroups” that contain all of the protists as well as animals, plants, and fungi that evolved from a common ancestor ( [link] ). The supergroups are hypothesized to be monophyletic, meaning that all organisms within each supergroup are hypothesized to have evolved from a single common ancestor, and thus all members are more closely related to each other than to organisms outside that group. There is still evidence lacking for the monophyly of some groups.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?