| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

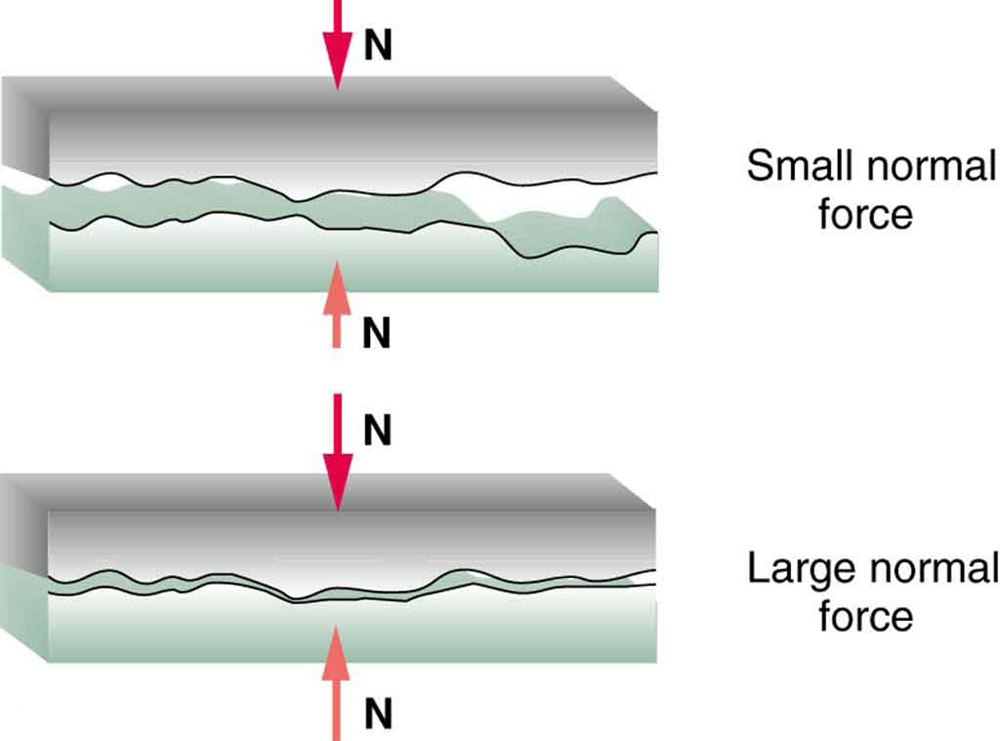

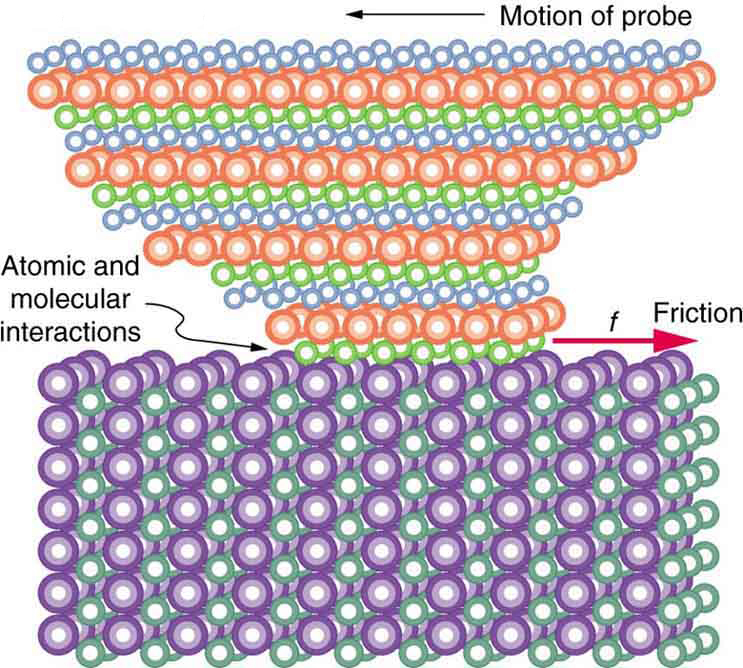

But the atomic-scale view promises to explain far more than the simpler features of friction. The mechanism for how heat is generated is now being determined. In other words, why do surfaces get warmer when rubbed? Essentially, atoms are linked with one another to form lattices. When surfaces rub, the surface atoms adhere and cause atomic lattices to vibrate—essentially creating sound waves that penetrate the material. The sound waves diminish with distance and their energy is converted into heat. Chemical reactions that are related to frictional wear can also occur between atoms and molecules on the surfaces. [link] shows how the tip of a probe drawn across another material is deformed by atomic-scale friction. The force needed to drag the tip can be measured and is found to be related to shear stress, which will be discussed later in this chapter. The variation in shear stress is remarkable (more than a factor of ) and difficult to predict theoretically, but shear stress is yielding a fundamental understanding of a large-scale phenomenon known since ancient times—friction.

The glue on a piece of tape can exert forces. Can these forces be a type of simple friction? Explain, considering especially that tape can stick to vertical walls and even to ceilings.

A physics major is cooking breakfast when he notices that the frictional force between his steel spatula and his Teflon frying pan is only 0.200 N. Knowing the coefficient of kinetic friction between the two materials, he quickly calculates the normal force. What is it?

Suppose you have a 120-kg wooden crate resting on a wood floor. (a) What maximum force can you exert horizontally on the crate without moving it? (b) If you continue to exert this force once the crate starts to slip, what will the magnitude of its acceleration then be?

(a) 588 N

(b)

Show that the acceleration of any object down an incline where friction behaves simply (that is, where ) is Note that the acceleration is independent of mass and reduces to the expression found in the previous problem when friction becomes negligibly small

Calculate the deceleration of a snow boarder going up a , slope assuming the coefficient of friction for waxed wood on wet snow. The result of [link] may be useful, but be careful to consider the fact that the snow boarder is going uphill. Explicitly show how you follow the steps in Problem-Solving Strategies .

(a) Calculate the acceleration of a skier heading down a slope, assuming the coefficient of friction for waxed wood on wet snow. (b) Find the angle of the slope down which this skier could coast at a constant velocity. You can neglect air resistance in both parts, and you will find the result of [link] to be useful. Explicitly show how you follow the steps in the Problem-Solving Strategies .

Calculate the maximum acceleration of a car that is heading up a slope (one that makes an angle of with the horizontal) under the following road conditions. Assume that only half the weight of the car is supported by the two drive wheels and that the coefficient of static friction is involved—that is, the tires are not allowed to slip during the acceleration. (Ignore rolling.) (a) On dry concrete. (b) On wet concrete. (c) On ice, assuming that , the same as for shoes on ice.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Repeat [link] for a car with four-wheel drive.

A contestant in a winter sporting event pushes a 45.0-kg block of ice across a frozen lake as shown in [link] (a). (a) Calculate the minimum force he must exert to get the block moving. (b) What is the magnitude of its acceleration once it starts to move, if that force is maintained?

(a)

(b)

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Newton's laws' conversation and receive update notifications?