| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In his 1865 publication, Mendel reported the results of his crosses involving seven different characteristics, each with two contrasting traits. A trait is defined as a variation in the physical appearance of a heritable characteristic. The characteristics included plant height, seed texture, seed color, flower color, pea pod size, pea pod color, and flower position. For the characteristic of flower color, for example, the two contrasting traits were white versus violet. To fully examine each characteristic, Mendel generated large numbers of F 1 and F 2 plants, reporting results from 19,959 F 2 plants alone. His findings were consistent.

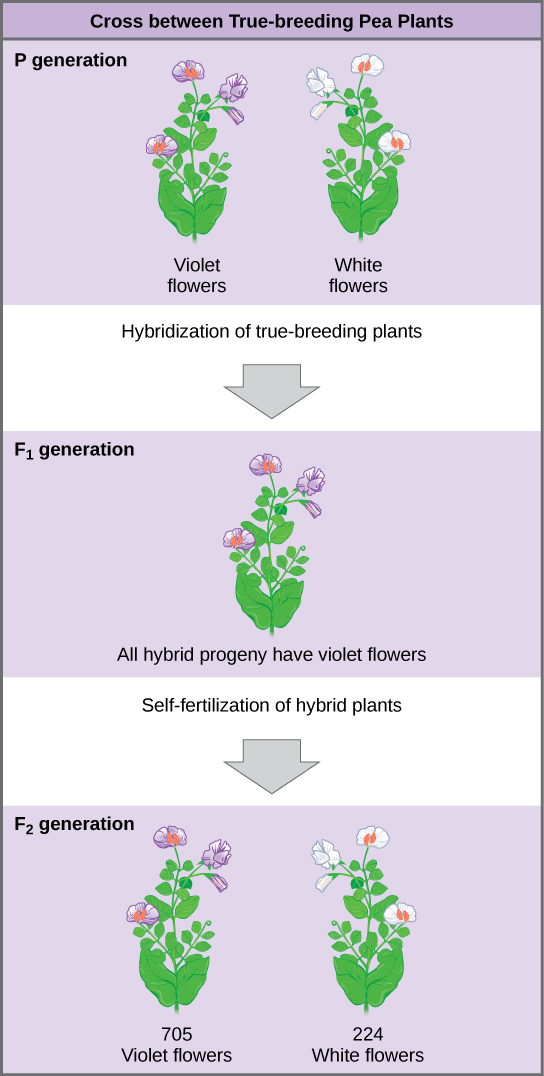

What results did Mendel find in his crosses for flower color? First, Mendel confirmed that he had plants that bred true for white or violet flower color. Regardless of how many generations Mendel examined, all self-crossed offspring of parents with white flowers had white flowers, and all self-crossed offspring of parents with violet flowers had violet flowers. In addition, Mendel confirmed that, other than flower color, the pea plants were physically identical.

Once these validations were complete, Mendel crossed plants with violet flowers to plants with white flowers. Mendel found that 100 percent of the F 1 hybrid generation had violet flowers. Conventional wisdom at that time would have predicted the hybrid flowers to be pale violet or for hybrid plants to have equal numbers of white and violet flowers. In other words, the contrasting parental traits were expected to blend in the offspring. Instead, Mendel’s results demonstrated that the white flower trait in the F 1 generation had completely disappeared.

Importantly, Mendel did not stop his experimentation there. He allowed the F 1 plants to self-fertilize and found that, of F 2 -generation plants, 705 had violet flowers and 224 had white flowers. This was a ratio of 3.15 violet flowers per one white flower, or approximately 3:1. When Mendel transferred pollen from a plant with violet flowers to the stigma of a plant with white flowers and vice versa, he obtained about the same ratio regardless of which parent, male or female, contributed which trait. For the other six characteristics Mendel examined, the F 1 and F 2 generations behaved in the same way as they had for flower color. One of the two traits would disappear completely from the F 1 generation only to reappear in the F 2 generation at a ratio of approximately 3:1 ( [link] ).

| The Results of Mendel’s Garden Pea Hybridizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Contrasting P Traits | F 1 Offspring Traits | F 2 Offspring Traits | F 2 Trait Ratios |

| Flower color | Violet vs. white | 100 percent violet |

|

3.15:1 |

| Flower position | Axial vs. terminal | 100 percent axial |

|

3.14:1 |

| Plant height | Tall vs. dwarf | 100 percent tall |

|

2.84:1 |

| Seed texture | Round vs. wrinkled | 100 percent round |

|

2.96:1 |

| Seed color | Yellow vs. green | 100 percent yellow |

|

3.01:1 |

| Pea pod texture | Inflated vs. constricted | 100 percent inflated |

|

2.95:1 |

| Pea pod color | Green vs. yellow | 100 percent green |

|

2.82:1 |

Upon compiling his results for many thousands of plants, Mendel concluded that the characteristics could be divided into expressed and latent traits. He called these, respectively, dominant and recessive traits. Dominant traits are those that are inherited unchanged in a hybridization. Recessive traits become latent, or disappear, in the offspring of a hybridization. The recessive trait does, however, reappear in the progeny of the hybrid offspring. An example of a dominant trait is the violet-flower trait. For this same characteristic (flower color), white-colored flowers are a recessive trait. The fact that the recessive trait reappeared in the F 2 generation meant that the traits remained separate (not blended) in the plants of the F 1 generation. Mendel also proposed that plants possessed two copies of the trait for the flower-color characteristic, and that each parent transmitted one of its two copies to its offspring, where they came together. Moreover, the physical observation of a dominant trait could mean that the genetic composition of the organism included two dominant versions of the characteristic or that it included one dominant and one recessive version. Conversely, the observation of a recessive trait meant that the organism lacked any dominant versions of this characteristic.

So why did Mendel repeatedly obtain 3:1 ratios in his crosses? To understand how Mendel deduced the basic mechanisms of inheritance that lead to such ratios, we must first review the laws of probability.

Probabilities are mathematical measures of likelihood. The empirical probability of an event is calculated by dividing the number of times the event occurs by the total number of opportunities for the event to occur. It is also possible to calculate theoretical probabilities by dividing the number of times that an event is expected to occur by the number of times that it could occur. Empirical probabilities come from observations, like those of Mendel. Theoretical probabilities come from knowing how the events are produced and assuming that the probabilities of individual outcomes are equal. A probability of one for some event indicates that it is guaranteed to occur, whereas a probability of zero indicates that it is guaranteed not to occur. An example of a genetic event is a round seed produced by a pea plant. In his experiment, Mendel demonstrated that the probability of the event “round seed” occurring was one in the F 1 offspring of true-breeding parents, one of which has round seeds and one of which has wrinkled seeds. When the F 1 plants were subsequently self-crossed, the probability of any given F 2 offspring having round seeds was now three out of four. In other words, in a large population of F 2 offspring chosen at random, 75 percent were expected to have round seeds, whereas 25 percent were expected to have wrinkled seeds. Using large numbers of crosses, Mendel was able to calculate probabilities and use these to predict the outcomes of other crosses.

Working with garden pea plants, Mendel found that crosses between parents that differed by one trait produced F 1 offspring that all expressed the traits of one parent. Observable traits are referred to as dominant, and non-expressed traits are described as recessive. When the offspring in Mendel’s experiment were self-crossed, the F 2 offspring exhibited the dominant trait or the recessive trait in a 3:1 ratio, confirming that the recessive trait had been transmitted faithfully from the original P 0 parent. Reciprocal crosses generated identical F 1 and F 2 offspring ratios. By examining sample sizes, Mendel showed that his crosses behaved reproducibly according to the laws of probability, and that the traits were inherited as independent events.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'General biology part i - mixed majors' conversation and receive update notifications?