| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

View this animation from Rockefeller University to see how dendritic cells act as sentinels in the body’s immune system.

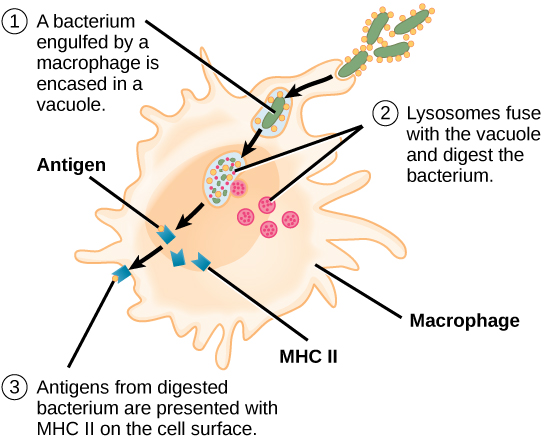

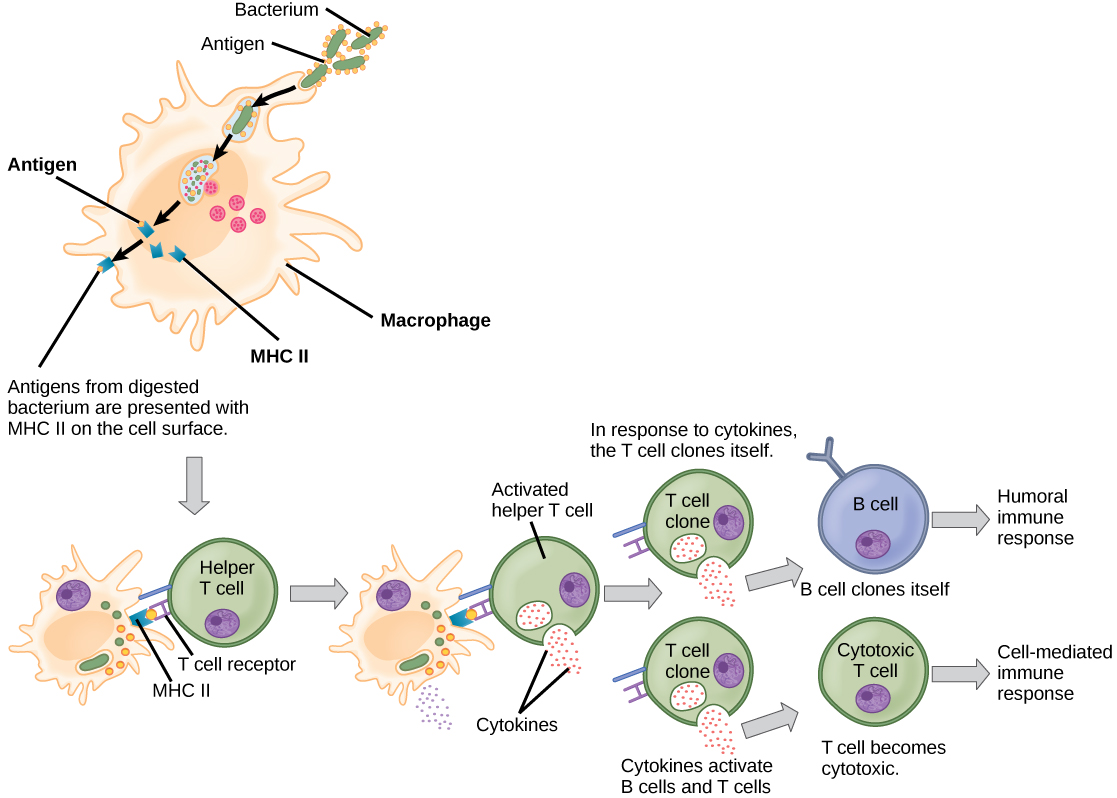

T cells have many functions. Some respond to APCs of the innate immune system and indirectly induce immune responses by releasing cytokines. Others stimulate B cells to start the humoral response as described previously. Another type of T cell detects APC signals and directly kills the infected cells, while some are involved in suppressing inappropriate immune reactions to harmless or “self” antigens.

There are two main types of T cells: helper T lymphocytes (T H ) and the cytotoxic T lymphocytes (T C ). The T H lymphocytes function indirectly to tell other immune cells about potential pathogens.

Cytotoxic T cells (T C ) are the key component of the cell-mediated part of the adaptive immune system and attack and destroy infected cells. T C cells are particularly important in protecting against viral infections; this is because viruses replicate within cells where they are shielded from extracellular contact with circulating antibodies. Once activated, the T C creates a large clone of cells with one specific set of cell-surface receptors, as in the case with clonal expansion of activated B cells. As with B cells, the clone includes active T C cells and inactive memory T C cells. The resulting active T C cells then identify infected host cells. Because of the time required to generate a population of clonal T and B cells, there is a delay in the adaptive immune response compared to the innate immune response.

T C cells attempt to identify and destroy infected cells before the pathogen can replicate and escape, thereby halting the progression of intracellular infections. T C cells also support NK lymphocytes to destroy early cancers. Cytokines secreted by the T H 1 response that stimulates macrophages also stimulate T C cells and enhance their ability to identify and destroy infected cells and tumors. A summary of how the humoral and cell-mediated immune responses are activated appears in [link] .

B plasma cells and T C cells are collectively called effector cells because they are involved in “effecting” (bringing about) the immune response of killing pathogens and infected host cells.

The adaptive immune system has a memory component that allows for a rapid and large response upon reinvasion of the same pathogen. During the adaptive immune response to a pathogen that has not been encountered before, known as the primary immune response , plasma cells secreting antibodies and differentiated T cells increase, then plateau over time. As B and T cells mature into effector cells, a subset of the naïve populations differentiates into B and T memory cells with the same antigen specificities ( [link] ). A memory cell is an antigen-specific B or T lymphocyte that does not differentiate into an effector cell during the primary immune response, but that can immediately become an effector cell on reexposure to the same pathogen. As the infection is cleared and pathogenic stimuli subside, the effectors are no longer needed and they undergo apoptosis. In contrast, the memory cells persist in the circulation.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Human biology' conversation and receive update notifications?