| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Folklore has it that more crazy behavior is seen during the time of the full moon (the Moon even gives a name to crazy behavior—“lunacy”). But, in fact, statistical tests of this “hypothesis” involving thousands of records from hospital emergency rooms and police files do not reveal any correlation of human behavior with the phases of the Moon. For example, homicides occur at the same rate during the new moon or the crescent moon as during the full moon. Most investigators believe that the real story is not that more crazy behavior happens on nights with a full moon, but rather that we are more likely to notice or remember such behavior with the aid of a bright celestial light that is up all night long.

During the two weeks following the full moon, the Moon goes through the same phases again in reverse order (points F, G, and H in [link] ), returning to new phase after about 29.5 days. About a week after the full moon, for example, the Moon is at third quarter , meaning that it is three-quarters of the way around (not that it is three-quarters illuminated—in fact, half of the visible side of the Moon is again dark). At this phase, the Moon is now rising around midnight and setting around noon.

Note that there is one thing quite misleading about [link] . If you look at the Moon in position E, although it is full in theory, it appears as if its illumination would in fact be blocked by a big fat Earth, and hence we would not see anything on the Moon except Earth’s shadow. In reality, the Moon is nowhere near as close to Earth (nor is its path so identical with the Sun’s in the sky) as this diagram (and the diagrams in most textbooks) might lead you to believe.

The Moon is actually 30 Earth-diameters away from us; Science and the Universe: A Brief Tour contains a diagram that shows the two objects to scale. And, since the Moon’s orbit is tilted relative to the path of the Sun in the sky, Earth’s shadow misses the Moon most months. That’s why we regularly get treated to a full moon. The times when Earth’s shadow does fall on the Moon are called lunar eclipses and are discussed in Eclipses of the Sun and Moon .

The week seems independent of celestial motions, although its length may have been based on the time between quarter phases of the Moon. In Western culture, the seven days of the week are named after the seven “wanderers” that the ancients saw in the sky: the Sun, the Moon, and the five planets visible to the unaided eye (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn).

In English, we can easily recognize the names Sun-day (Sunday), Moon-day (Monday), and Saturn-day (Saturday), but the other days are named after the Norse equivalents of the Roman gods that gave their names to the planets. In languages more directly related to Latin, the correspondences are clearer. Wednesday, Mercury’s day, for example, is mercoledi in Italian, mercredi in French, and miércoles in Spanish. Mars gives its name to Tuesday ( martes in Spanish), Jupiter or Jove to Thursday ( giovedi in Italian), and Venus to Friday ( vendredi in French).

There is no reason that the week has to have seven days rather than five or eight. It is interesting to speculate that if we had lived in a planetary system where more planets were visible without a telescope, the Beatles could have been right and we might well have had “Eight Days a Week.”

View this animation to see the phases of the Moon as it orbits Earth and as Earth orbits the Sun.

The Moon’s sidereal period—that is, the period of its revolution about Earth measured with respect to the stars—is a little over 27 days: the sidereal month is 27.3217 days to be exact. The time interval in which the phases repeat—say, from full to full—is the solar month , 29.5306 days. The difference results from Earth’s motion around the Sun. The Moon must make more than a complete turn around the moving Earth to get back to the same phase with respect to the Sun. As we saw, the Moon changes its position on the celestial sphere rather rapidly: even during a single evening, the Moon creeps visibly eastward among the stars, traveling its own width in a little less than 1 hour. The delay in moonrise from one day to the next caused by this eastward motion averages about 50 minutes.

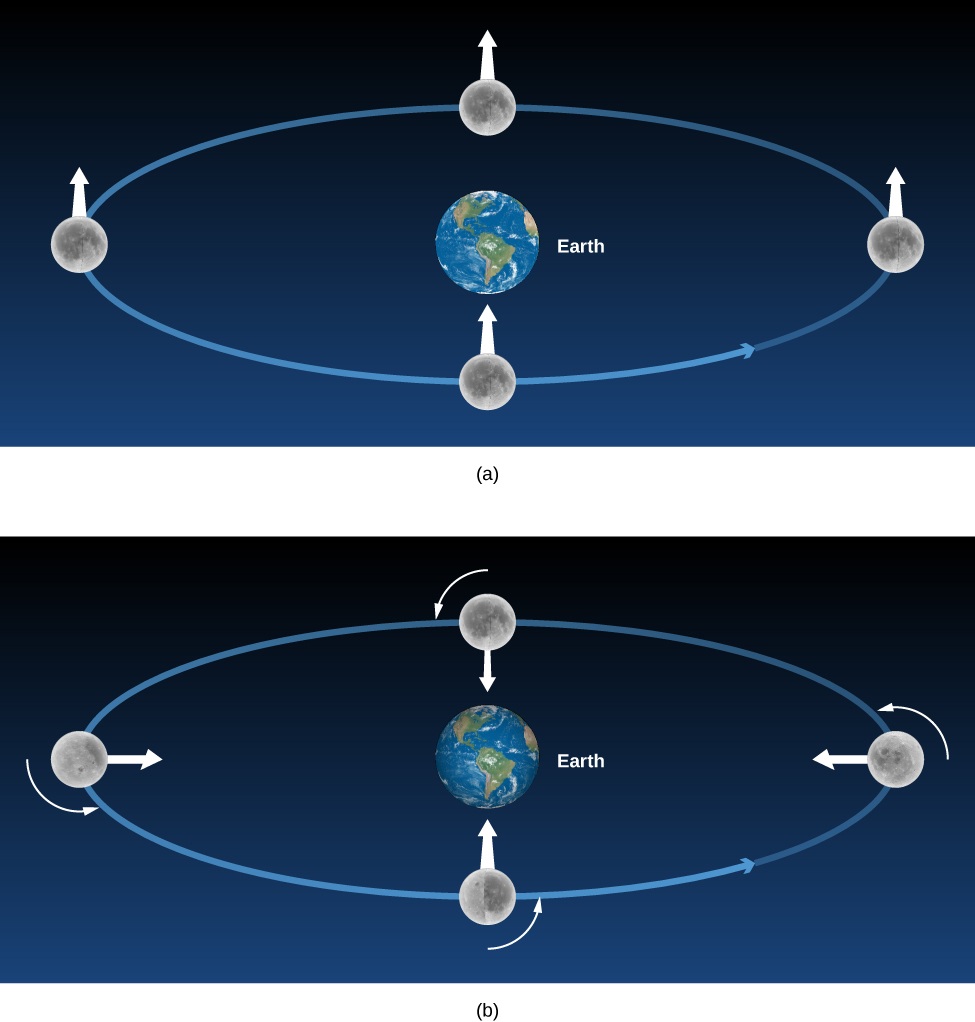

The Moon rotates on its axis in exactly the same time that it takes to revolve about Earth. As a consequence, the Moon always keeps the same face turned toward Earth ( [link] ). You can simulate this yourself by “orbiting” your roommate or another volunteer. Start by facing your roommate. If you make one rotation (spin) with your shoulders in the exact same time that you revolve around him or her, you will continue to face your roommate during the whole “orbit.” As we will see in coming chapters, our Moon is not the only world that exhibits this behavior, which scientists call synchronous rotation .

The differences in the Moon’s appearance from one night to the next are due to changing illumination by the Sun, not to its own rotation. You sometimes hear the back side of the Moon (the side we never see) called the “dark side.” This is a misunderstanding of the real situation: which side is light and which is dark changes as the Moon moves around Earth. The back side is dark no more frequently than the front side. Since the Moon rotates, the Sun rises and sets on all sides of the Moon. With apologies to Pink Floyd, there is simply no regular “Dark Side of the Moon.”

The Moon’s monthly cycle of phases results from the changing angle of its illumination by the Sun. The full moon is visible in the sky only during the night; other phases are visible during the day as well. Because its period of revolution is the same as its period of rotation, the Moon always keeps the same face toward Earth.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?