| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Energy can no longer be generated by hydrogen fusion in the stellar core because the hydrogen is all gone and, as we will see, the fusion of helium requires much higher temperatures. Since the central temperature is not yet high enough to fuse helium, there is no nuclear energy source to supply heat to the central region of the star. The long period of stability now ends, gravity again takes over, and the core begins to contract. Once more, the star’s energy is partially supplied by gravitational energy, in the way described by Kelvin and Helmholtz (see Sources of Sunshine: Thermal and Gravitational Energy ). As the star’s core shrinks, the energy of the inward-falling material is converted to heat.

The heat generated in this way, like all heat, flows outward to where it is a bit cooler. In the process, the heat raises the temperature of a layer of hydrogen that spent the whole long main-sequence time just outside the core. Like an understudy waiting in the wings of a hit Broadway show for a chance at fame and glory, this hydrogen was almost (but not quite) hot enough to undergo fusion and take part in the main action that sustains the star. Now, the additional heat produced by the shrinking core puts this hydrogen “over the limit,” and a shell of hydrogen nuclei just outside the core becomes hot enough for hydrogen fusion to begin.

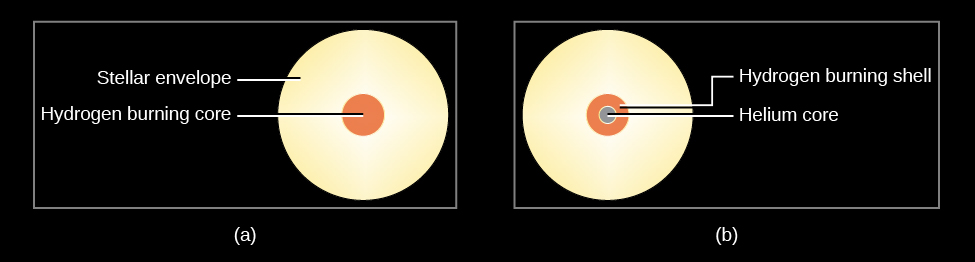

New energy produced by fusion of this hydrogen now pours outward from this shell and begins to heat up layers of the star farther out, causing them to expand. Meanwhile, the helium core continues to contract, producing more heat right around it. This leads to more fusion in the shell of fresh hydrogen outside the core ( [link] ). The additional fusion produces still more energy, which also flows out into the upper layer of the star.

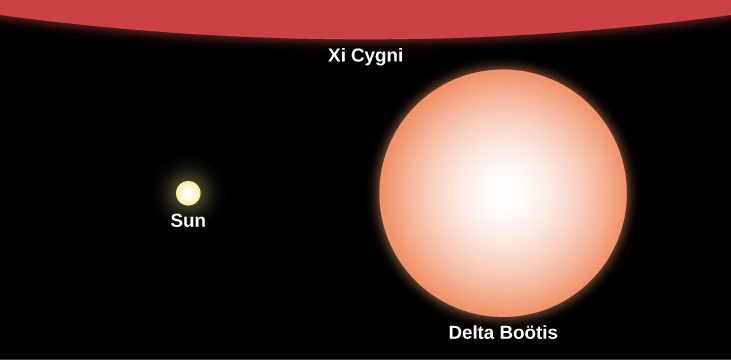

Most stars actually generate more energy each second when they are fusing hydrogen in the shell surrounding the helium core than they did when hydrogen fusion was confined to the central part of the star; thus, they increase in luminosity. With all the new energy pouring outward, the outer layers of the star begin to expand, and the star eventually grows and grows until it reaches enormous proportions ( [link] ).

When you take the lid off a pot of boiling water, the steam can expand and it cools down. In the same way, the expansion of a star’s outer layers causes the temperature at the surface to decrease. As it cools, the star’s overall color becomes redder. (We saw in Radiation and Spectra that a red color corresponds to cooler temperature.)

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Astronomy' conversation and receive update notifications?