| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

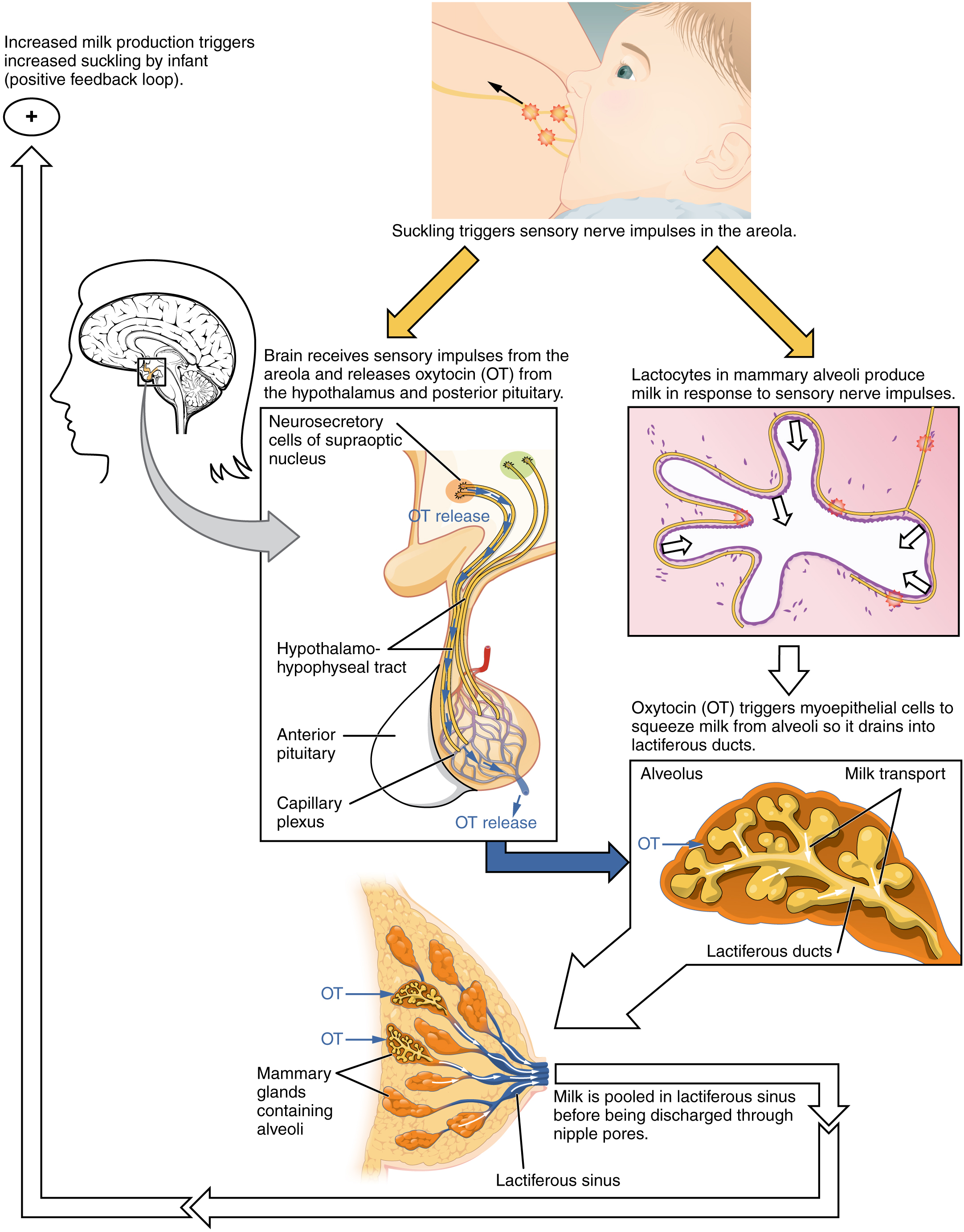

When the infant suckles, sensory nerve fibers in the areola trigger a neuroendocrine reflex that results in milk secretion from lactocytes into the alveoli. The posterior pituitary releases oxytocin, which stimulates myoepithelial cells to squeeze milk from the alveoli so it can drain into the lactiferous ducts, collect in the lactiferous sinuses, and discharge through the nipple pores. It takes less than 1 minute from the time when an infant begins suckling (the latent period) until milk is secreted (the let-down). [link] summarizes the positive feedback loop of the let-down reflex .

The prolactin-mediated synthesis of milk changes with time. Frequent milk removal by breastfeeding (or pumping) will maintain high circulating prolactin levels for several months. However, even with continued breastfeeding, baseline prolactin will decrease over time to its pre-pregnancy level. In addition to prolactin and oxytocin, growth hormone, cortisol, parathyroid hormone, and insulin contribute to lactation, in part by facilitating the transport of maternal amino acids, fatty acids, glucose, and calcium to breast milk.

In the final weeks of pregnancy, the alveoli swell with colostrum , a thick, yellowish substance that is high in protein but contains less fat and glucose than mature breast milk ( [link] ). Before childbirth, some women experience leakage of colostrum from the nipples. In contrast, mature breast milk does not leak during pregnancy and is not secreted until several days after childbirth.

| Compositions of Human Colostrum, Mature Breast Milk, and Cow’s Milk (g/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Human colostrum | Human breast milk | Cow’s milk* | |

| Total protein | 23 | 11 | 31 |

| Immunoglobulins | 19 | 0.1 | 1 |

| Fat | 30 | 45 | 38 |

| Lactose | 57 | 71 | 47 |

| Calcium | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| Phosphorus | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.90 |

| Sodium | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.41 |

Colostrum is secreted during the first 48–72 hours postpartum. Only a small volume of colostrum is produced—approximately 3 ounces in a 24-hour period—but it is sufficient for the newborn in the first few days of life. Colostrum is rich with immunoglobulins, which confer gastrointestinal, and also likely systemic, immunity as the newborn adjusts to a nonsterile environment.

After about the third postpartum day, the mother secretes transitional milk that represents an intermediate between mature milk and colostrum. This is followed by mature milk from approximately postpartum day 10 (see [link] ). As you can see in the accompanying table, cow’s milk is not a substitute for breast milk. It contains less lactose, less fat, and more protein and minerals. Moreover, the proteins in cow’s milk are difficult for an infant’s immature digestive system to metabolize and absorb.

The first few weeks of breastfeeding may involve leakage, soreness, and periods of milk engorgement as the relationship between milk supply and infant demand becomes established. Once this period is complete, the mother will produce approximately 1.5 liters of milk per day for a single infant, and more if she has twins or triplets. As the infant goes through growth spurts, the milk supply constantly adjusts to accommodate changes in demand. A woman can continue to lactate for years, but once breastfeeding is stopped for approximately 1 week, any remaining milk will be reabsorbed; in most cases, no more will be produced, even if suckling or pumping is resumed.

Mature milk changes from the beginning to the end of a feeding. The early milk, called foremilk , is watery, translucent, and rich in lactose and protein. Its purpose is to quench the infant’s thirst. Hindmilk is delivered toward the end of a feeding. It is opaque, creamy, and rich in fat, and serves to satisfy the infant’s appetite.

During the first days of a newborn’s life, it is important for meconium to be cleared from the intestines and for bilirubin to be kept low in the circulation. Recall that bilirubin, a product of erythrocyte breakdown, is processed by the liver and secreted in bile. It enters the gastrointestinal tract and exits the body in the stool. Breast milk has laxative properties that help expel meconium from the intestines and clear bilirubin through the excretion of bile. A high concentration of bilirubin in the blood causes jaundice. Some degree of jaundice is normal in newborns, but a high level of bilirubin—which is neurotoxic—can cause brain damage. Newborns, who do not yet have a fully functional blood–brain barrier, are highly vulnerable to the bilirubin circulating in the blood. Indeed, hyperbilirubinemia, a high level of circulating bilirubin, is the most common condition requiring medical attention in newborns. Newborns with hyperbilirubinemia are treated with phototherapy because UV light helps to break down the bilirubin quickly.

The lactating mother supplies all the hydration and nutrients that a growing infant needs for the first 4–6 months of life. During pregnancy, the body prepares for lactation by stimulating the growth and development of branching lactiferous ducts and alveoli lined with milk-secreting lactocytes, and by creating colostrum. These functions are attributable to the actions of several hormones, including prolactin. Following childbirth, suckling triggers oxytocin release, which stimulates myoepithelial cells to squeeze milk from alveoli. Breast milk then drains toward the nipple pores to be consumed by the infant. Colostrum, the milk produced in the first postpartum days, provides immunoglobulins that increase the newborn’s immune defenses. Colostrum, transitional milk, and mature breast milk are ideally suited to each stage of the newborn’s development, and breastfeeding helps the newborn’s digestive system expel meconium and clear bilirubin. Mature milk changes from the beginning to the end of a feeding. Foremilk quenches the infant’s thirst, whereas hindmilk satisfies the infant’s appetite.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?