| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The idea of the social construction of the illness experience is based on the concept of reality as a social construction. In other words, there is no objective reality; there are only our own perceptions of it. The social construction of the illness experience deals with such issues as the way some patients control the manner in which they reveal their diseases and the lifestyle adaptations patients develop to cope with their illnesses.

In terms of constructing the illness experience, culture and individual personality both play a significant role. For some people, a long-term illness can have the effect of making their world smaller, more defined by the illness than anything else. For others, illness can be a chance for discovery, for re-imaging a new self (Conrad and Barker 2007). Culture plays a huge role in how an individual experiences illness. Widespread diseases like AIDS or breast cancer have specific cultural markers that have changed over the years and that govern how individuals—and society—view them.

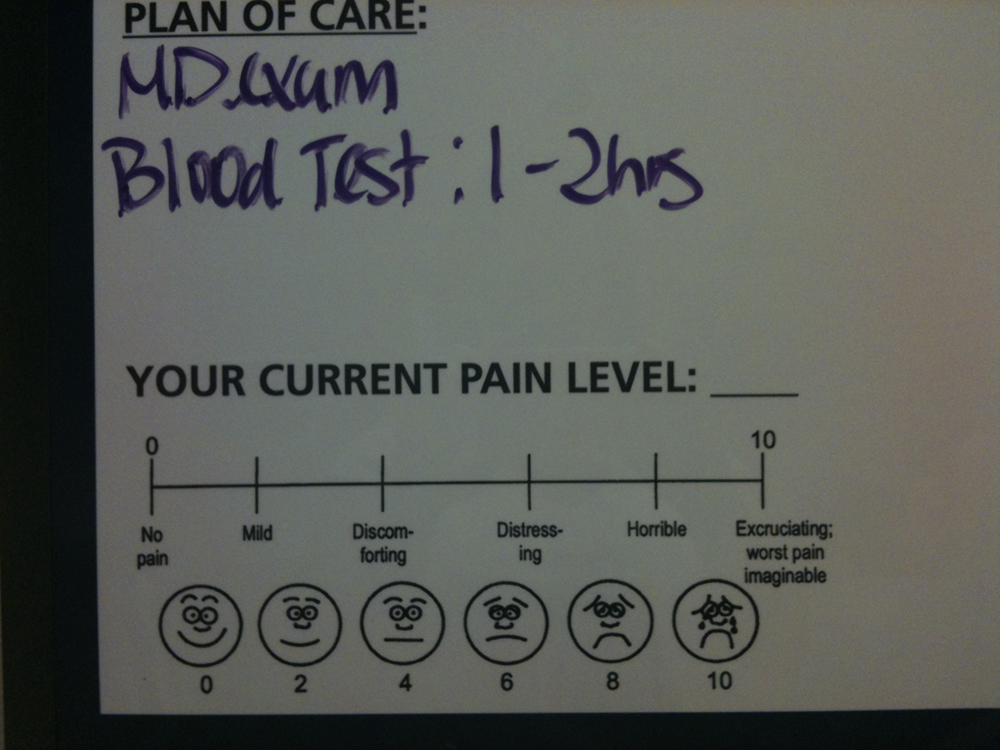

Today, many institutions of wellness acknowledge the degree to which individual perceptions shape the nature of health and illness. Regarding physical activity, for instance, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that individuals use a standard level of exertion to assess their physical activity. This Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) gives a more complete view of an individual’s actual exertion level, since heartrate or pulse measurements may be affected by medication or other issues (Centers for Disease Control 2011a). Similarly, many medical professionals use a comparable scale for perceived pain to help determine pain management strategies.

Conrad and Barker show how medical knowledge is socially constructed; that is, it can both reflect and reproduce inequalities in gender, class, race, and ethnicity. Conrad and Barker (2011) use the example of the social construction of women’s health and how medical knowledge has changed significantly in the course of a few generations. For instance, in the early nineteenth century, pregnant women were discouraged from driving or dancing for fear of harming the unborn child, much as they are discouraged, with more valid reason, from smoking or drinking alcohol today.

Every October, the world turns pink. Football and baseball players wear pink accessories. Skyscrapers and large public buildings are lit with pink lights at night. Shoppers can choose from a huge array of pink products. In 2014, people wanting to support the fight against breast cancer could purchase any of the following pink products: KitchenAid mixers, Master Lock padlocks and bike chains, Wilson tennis rackets, Fiat cars, and Smith&Wesson handguns. You read that correctly. The goal of all these pink products is to raise awareness and money for breast cancer. However, the relentless creep of pink has many people wondering if the pink marketing juggernaut has gone too far.

Pink has been associated with breast cancer since 1991, when the Susan G. Komen Foundation handed out pink ribbons at its 1991 Race for the Cure event. Since then, the pink ribbon has appeared on countless products, and then by extension, the color pink has come to represent support for a cure of the disease. No one can argue about the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s mission—to find a cure for breast cancer—or the fact that the group has raised millions of dollars for research and care. However, some people question if, or how much, all these products really help in the fight against breast cancer (Begos 2011).

The advocacy group Breast Cancer Action (BCA) position themselves as watchdogs of other agencies fighting breast cancer. They accept no funding from entities, like those in the pharmaceutical industry, with potential profit connections to this health industry. They’ve developed a trademarked “Think Before You Pink” campaign to provoke consumer questioning of the end contributions made to breast cancer by companies hawking pink wares. They do not advise against “pink” purchases; they just want consumers to be informed about how much money is involved, where it comes from, and where it will go. For instance, what percentage of each purchase goes to breast cancer causes? BCA does not judge how much is enough, but it informs customers and then encourages them to consider whether they feel the amount is enough (Think Before You Pink 2012).

BCA also suggests that consumers make sure that the product they are buying does not actually contribute to breast cancer, a phenomenon they call “pinkwashing.” This issue made national headlines in 2010, when the Susan G. Komen Foundation partnered with Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) on a promotion called “Buckets for the Cure.” For every bucket of grilled or regular fried chicken, KFC would donate fifty cents to the Komen Foundation, with the goal of reaching 8 million dollars: the largest single donation received by the foundation. However, some critics saw the partnership as an unholy alliance. Higher body fat and eating fatty foods has been linked to increased cancer risks, and detractors, including BCA, called the Komen Foundation out on this apparent contradiction of goals. Komen’s response was that the program did a great deal to raise awareness in low-income communities, where Komen previously had little outreach (Hutchison 2010).

What do you think? Are fundraising and awareness important enough to trump issues of health? What other examples of “pinkwashing” can you think of?

Medical sociology is the systematic study of how humans manage issues of health and illness, disease and disorders, and healthcare for both the sick and the healthy. The social construction of health explains how society shapes and is shaped by medical ideas.

Pick a common illness and describe which parts of it are medically constructed, and which parts are socially constructed.

What diseases are the most stigmatized? Which are the least? Is this different in different cultures or social classes?

Spend some time on the two web sites below. How do they present differing views of the vaccination controversy? Freedom of Choice is Not Free: Vaccination News: (External Link) and Shot by Shot: Stories of Vaccine-Preventable Illnesses: (External Link)

Begos, Kevin. 2011. “Pinkwashing For Breast Cancer Awareness Questioned.” Retrieved December 16, 2011 ( (External Link) ).

Centers for Disease Control. 2011a. “Perceived Exertion (Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 12, 2011 ( (External Link) ).

Conrad, Peter, and Kristin Barker. 2010. “The Social Construction of Illness: Key Insights and Policy Implications.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51:67–79.

Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity . London: Penguin.

Hutchison, Courtney. 2010. “Fried Chicken for the Cure?” ABC News Medical Unit. Retrieved December 16, 2011 ( (External Link) ).

Sartorius, Norman. 2007. “Stigmatized Illness and Health Care.” The Croatian Medical Journal 48(3):396–397. Retrieved December 12, 2011 ( (External Link) ).

Think Before You Pink. 2012. “Before You Buy Pink.” Retrieved December 16, 2011 ( (External Link) ).

“Vaccines and Immunizations.” 2011. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 16, 2011 ( (External Link) ).

World Health Organization. .n.d. “Definition of Health.” Retrieved December 12, 2011 ( (External Link) ).

World Health Organization: “Health Promotion Glossary Update.” Retrieved December 12, 2011 ( (External Link) ).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Introduction to sociology 2e' conversation and receive update notifications?