| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In addition to these leadership functions, there are three different leadership styles . Democratic leaders encourage group participation in all decision making. These leaders work hard to build consensus before choosing a course of action and moving forward. This type of leader is particularly common, for example, in a club where the members vote on which activities or projects to pursue. These leaders can be well liked, but there is often a challenge that the work will proceed slowly since consensus building is time-consuming. A further risk is that group members might pick sides and entrench themselves into opposing factions rather than reaching a solution. In contrast, a laissez-faire leader (French for “leave it alone”) is hands-off, allowing group members to self-manage and make their own decisions. An example of this kind of leader might be an art teacher who opens the art cupboard, leaves materials on the shelves, and tells students to help themselves and make some art. While this style can work well with highly motivated and mature participants who have clear goals and guidelines, it risks group dissolution and a lack of progress. As the name suggests, authoritarian leaders issue orders and assigns tasks. These leaders are clear instrumental leaders with a strong focus on meeting goals. Often, entrepreneurs fall into this mold, like Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. Not surprisingly, this type of leader risks alienating the workers. There are times, however, when this style of leadership can be required. In different circumstances, each of these leadership styles can be effective and successful. Consider what leadership style you prefer. Why? Do you like the same style in different areas of your life, such as a classroom, a workplace, and a sports team?

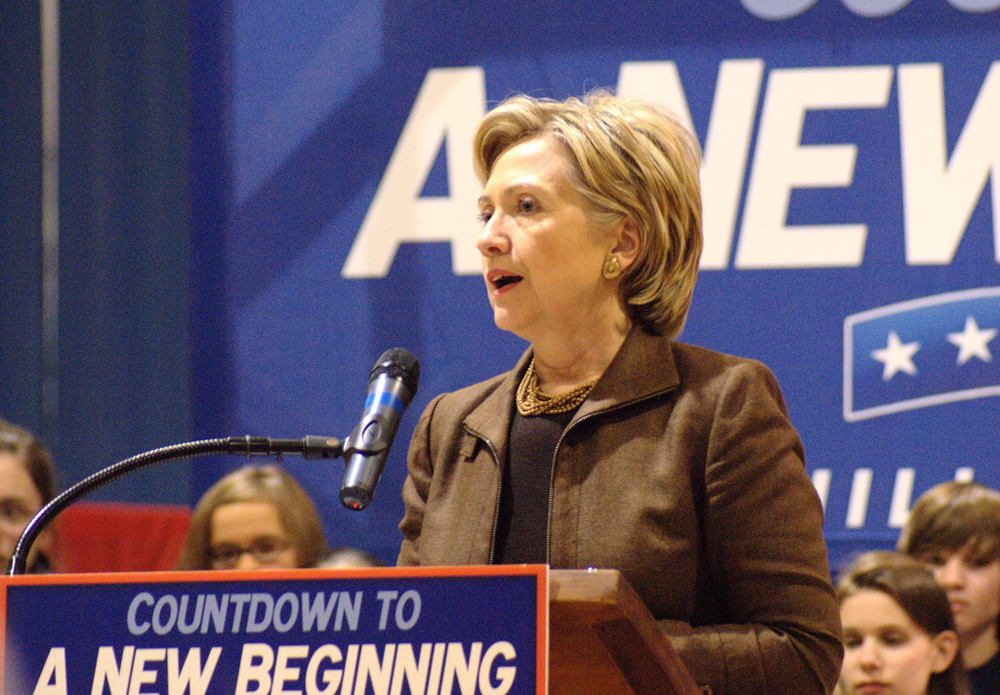

The 2008 presidential election marked a dynamic change when two female politicians entered the race. Of the 200 people who have run for president during the country’s history, fewer than 30 have been women. Democratic presidential candidate and former First Lady Hillary Clinton was both famously polarizing and popular. She had almost as many passionate supporters as she did people who reviled her.

On the other side of the aisle was Republican vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin. The former governor of Alaska, Palin was, to some, the perfect example of the modern woman. She juggled her political career with raising a growing family, and relied heavily on the use of social media to spread her message.

So what light did these candidates’ campaigns shed on the possibilities of a female presidency? According to some political analysts, women candidates face a paradox: They must be as tough as their male opponents on issues such as foreign policy or risk appearing weak. However, the stereotypical expectation of women as expressive leaders is still prevalent. Consider that Hillary Clinton’s popularity surged in her 2008 campaign after she cried on the campaign trail. It was enough for the New York Times to publish an editorial, “Can Hillary Cry Her Way Back to the White House?” (Dowd 2008). Harsh, but her approval ratings soared afterwards. In fact, many compared it to how politically likable she was in the aftermath of President Clinton’s Monica Lewinsky scandal. Sarah Palin’s expressive qualities were promoted to a greater degree. While she has benefited from the efforts of feminists before her, she self-identified as a traditional woman with traditional values, a point she illustrated by frequently bringing her young children up on stage with her.

So what does this mean for women who would be president, and for those who would vote for them? On the positive side, a recent study of 18- to 25-year-old women that asked whether female candidates in the 2008 election made them believe a woman would be president during their lifetime found that the majority thought they would (Weeks 2011). And the more that young women demand female candidates, the more commonplace female contenders will become. Women as presidential candidates may no longer be a novelty with the focus of their campaign, no matter how obliquely, on their gender. Some, however, remain skeptical. As one political analyst said bluntly, “women don’t succeed in politics––or other professions––unless they act like men. The standard for running for national office remains distinctly male” (Weeks 2011).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Introduction to sociology' conversation and receive update notifications?