| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

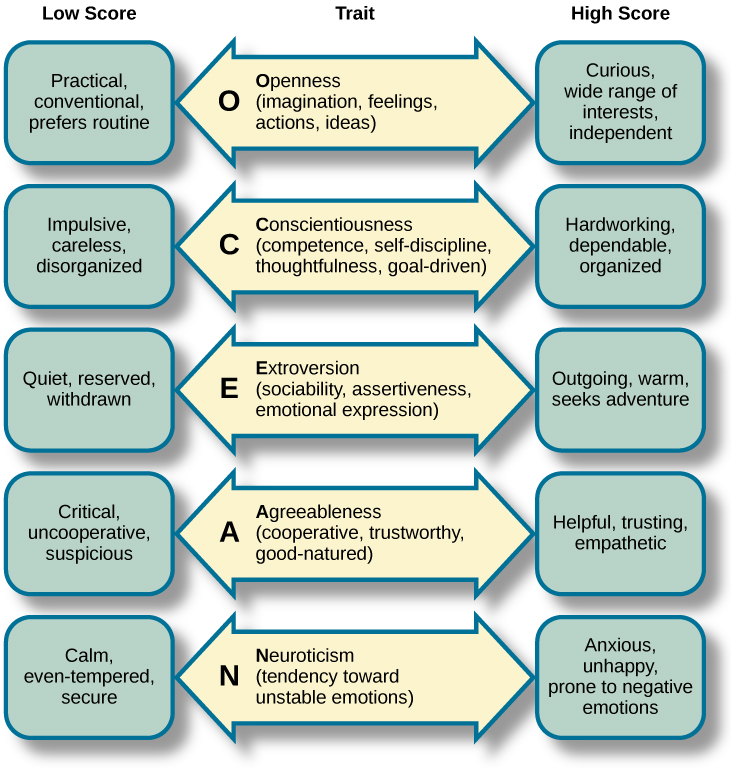

More recently, the study of personality has taken on a more quantitative approach. Rather than explaining how personality arises, research is focused on identifying personality traits , measuring these traits, and determining how these traits interact in a particular context to determine how a person will behave in any given situation. Personality traits are relatively consistent patterns of thought and behavior, and many have proposed that five trait dimensions are sufficient to capture the variations in personality seen across individuals. These five dimensions are known as the “Big Five” or the Five Factor model , and include dimensions of conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion ( [link] ). Each of these traits has been demonstrated to be relatively stable over the lifespan (e.g., Rantanen, Metsäpelto, Feldt, Pulkinnen, and Kokko, 2007; Soldz&Vaillant, 1999; McCrae&Costa, 2008) and is influenced by genetics (e.g., Jang, Livesly, and Vernon, 1996).

Social psychology focuses on how we interact with and relate to others. Social psychologists conduct research on a wide variety of topics that include differences in how we explain our own behavior versus how we explain the behaviors of others, prejudice, and attraction, and how we resolve interpersonal conflicts. Social psychologists have also sought to determine how being among other people changes our own behavior and patterns of thinking.

There are many interesting examples of social psychological research, and you will read about many of these in a later chapter of this textbook. Until then, you will be introduced to one of the most controversial psychological studies ever conducted. Stanley Milgram was an American social psychologist who is most famous for research that he conducted on obedience. After the holocaust, in 1961, a Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, who was accused of committing mass atrocities, was put on trial. Many people wondered how German soldiers were capable of torturing prisoners in concentration camps, and they were unsatisfied with the excuses given by soldiers that they were simply following orders. At the time, most psychologists agreed that few people would be willing to inflict such extraordinary pain and suffering, simply because they were obeying orders. Milgram decided to conduct research to determine whether or not this was true ( [link] ). As you will read later in the text, Milgram found that nearly two-thirds of his participants were willing to deliver what they believed to be lethal shocks to another person, simply because they were instructed to do so by an authority figure (in this case, a man dressed in a lab coat). This was in spite of the fact that participants received payment for simply showing up for the research study and could have chosen not to inflict pain or more serious consequences on another person by withdrawing from the study. No one was actually hurt or harmed in any way, Milgram’s experiment was a clever ruse that took advantage of research confederates, those who pretend to be participants in a research study who are actually working for the researcher and have clear, specific directions on how to behave during the research study (Hock, 2009). Milgram’s and others’ studies that involved deception and potential emotional harm to study participants catalyzed the development of ethical guidelines for conducting psychological research that discourage the use of deception of research subjects, unless it can be argued not to cause harm and, in general, requiring informed consent of participants.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Psychology' conversation and receive update notifications?