| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Eating is essential for survival, and it is no surprise that a drive like hunger exists to ensure that we seek out sustenance. While this chapter will focus primarily on the physiological mechanisms that regulate hunger and eating, powerful social, cultural, and economic influences also play important roles. This section will explain the regulation of hunger, eating, and body weight, and we will discuss the adverse consequences of disordered eating.

There are a number of physiological mechanisms that serve as the basis for hunger. When our stomachs are empty, they contract, causing both hunger pangs and the secretion of chemical messages that travel to the brain to serve as a signal to initiate feeding behavior. When our blood glucose levels drop, the pancreas and liver generate a number of chemical signals that induce hunger (Konturek et al., 2003; Novin, Robinson, Culbreth,&Tordoff, 1985) and thus initiate feeding behavior.

For most people, once they have eaten, they feel satiation , or fullness and satisfaction, and their eating behavior stops. Like the initiation of eating, satiation is also regulated by several physiological mechanisms. As blood glucose levels increase, the pancreas and liver send signals to shut off hunger and eating (Drazen&Woods, 2003; Druce, Small,&Bloom, 2004; Greary, 1990). The food’s passage through the gastrointestinal tract also provides important satiety signals to the brain (Woods, 2004), and fat cells release leptin , a satiety hormone.

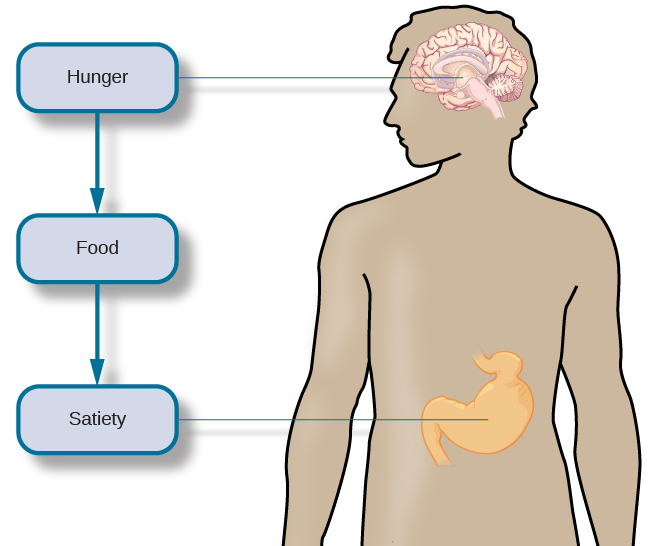

The various hunger and satiety signals that are involved in the regulation of eating are integrated in the brain. Research suggests that several areas of the hypothalamus and hindbrain are especially important sites where this integration occurs (Ahima&Antwi, 2008; Woods&D’Alessio, 2008). Ultimately, activity in the brain determines whether or not we engage in feeding behavior ( [link] ).

Our body weight is affected by a number of factors, including gene-environment interactions, and the number of calories we consume versus the number of calories we burn in daily activity. If our caloric intake exceeds our caloric use, our bodies store excess energy in the form of fat. If we consume fewer calories than we burn off, then stored fat will be converted to energy. Our energy expenditure is obviously affected by our levels of activity, but our body’s metabolic rate also comes into play. A person’s metabolic rate is the amount of energy that is expended in a given period of time, and there is tremendous individual variability in our metabolic rates. People with high rates of metabolism are able to burn off calories more easily than those with lower rates of metabolism.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Psychology' conversation and receive update notifications?