| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Forces are given many names, such as push, pull, thrust, and weight. Traditionally, forces have been grouped into several categories and given names relating to their source, how they are transmitted, or their effects. Several of these categories are discussed in this section, together with some interesting applications. Further examples of forces are discussed later in this text.

A catalog of forces will be useful for reference as we solve various problems involving force and motion. These forces include normal force, tension, friction, and spring force.

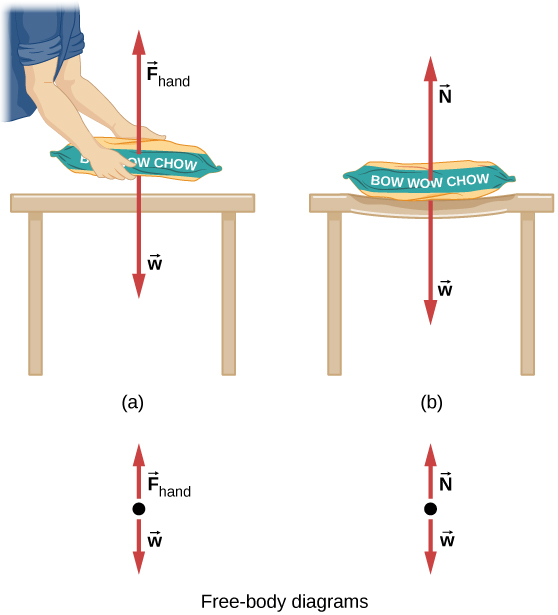

Weight (also called the force of gravity) is a pervasive force that acts at all times and must be counteracted to keep an object from falling. You must support the weight of a heavy object by pushing up on it when you hold it stationary, as illustrated in [link] (a). But how do inanimate objects like a table support the weight of a mass placed on them, such as shown in [link] (b)? When the bag of dog food is placed on the table, the table sags slightly under the load. This would be noticeable if the load were placed on a card table, but even a sturdy oak table deforms when a force is applied to it. Unless an object is deformed beyond its limit, it will exert a restoring force much like a deformed spring (or a trampoline or diving board). The greater the deformation, the greater the restoring force. Thus, when the load is placed on the table, the table sags until the restoring force becomes as large as the weight of the load. At this point, the net external force on the load is zero. That is the situation when the load is stationary on the table. The table sags quickly and the sag is slight, so we do not notice it. But it is similar to the sagging of a trampoline when you climb onto it.

We must conclude that whatever supports a load, be it animate or not, must supply an upward force equal to the weight of the load, as we assumed in a few of the previous examples. If the force supporting the weight of an object, or a load, is perpendicular to the surface of contact between the load and its support, this force is defined as a normal force and here is given by the symbol (This is not the newton unit for force, or N.) The word normal means perpendicular to a surface. This means that the normal force experienced by an object resting on a horizontal surface can be expressed in vector form as follows:

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'University physics volume 1' conversation and receive update notifications?