| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The study of motion is called kinematics , but kinematics only describes the way objects move—their velocity and their acceleration. Dynamics is the study of how forces affect the motion of objects and systems. It considers the causes of motion of objects and systems of interest, where a system is anything being analyzed. The foundation of dynamics are the laws of motion stated by Isaac Newton (1642–1727). These laws provide an example of the breadth and simplicity of principles under which nature functions. They are also universal laws in that they apply to situations on Earth and in space.

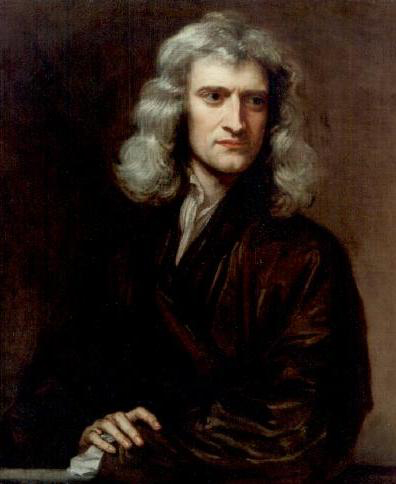

Newton’s laws of motion were just one part of the monumental work that has made him legendary ( [link] ). The development of Newton’s laws marks the transition from the Renaissance to the modern era. Not until the advent of modern physics was it discovered that Newton’s laws produce a good description of motion only when the objects are moving at speeds much less than the speed of light and when those objects are larger than the size of most molecules (about m in diameter). These constraints define the realm of Newtonian mechanics. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Albert Einstein (1879–1955) developed the theory of relativity and, along with many other scientists, quantum mechanics. Quantum mechanics does not have the constraints present in Newtonian physics. All of the situations we consider in this chapter, and all those preceding the introduction of relativity in Relativity , are in the realm of Newtonian physics.

Dynamics is the study of the forces that cause objects and systems to move. To understand this, we need a working definition of force. An intuitive definition of force —that is, a push or a pull—is a good place to start. We know that a push or a pull has both magnitude and direction (therefore, it is a vector quantity), so we can define force as the push or pull on an object with a specific magnitude and direction. Force can be represented by vectors or expressed as a multiple of a standard force.

The push or pull on an object can vary considerably in either magnitude or direction. For example, a cannon exerts a strong force on a cannonball that is launched into the air. In contrast, Earth exerts only a tiny downward pull on a flea. Our everyday experiences also give us a good idea of how multiple forces add. If two people push in different directions on a third person, as illustrated in [link] , we might expect the total force to be in the direction shown. Since force is a vector, it adds just like other vectors. Forces, like other vectors, are represented by arrows and can be added using the familiar head-to-tail method or trigonometric methods. These ideas were developed in Vectors .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'University physics volume 1' conversation and receive update notifications?