| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

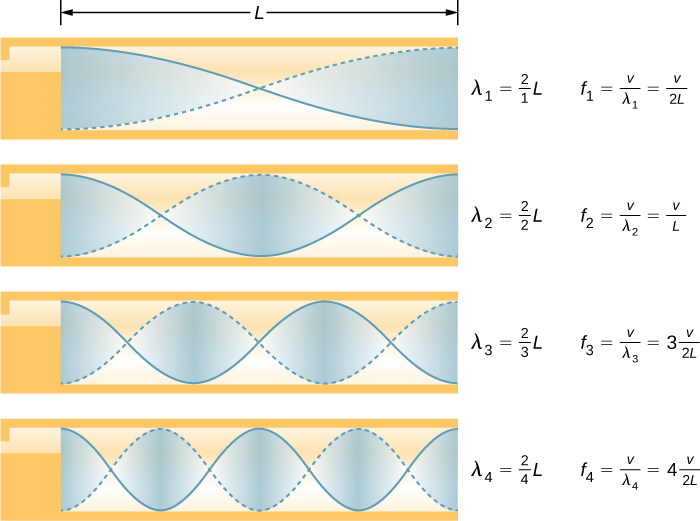

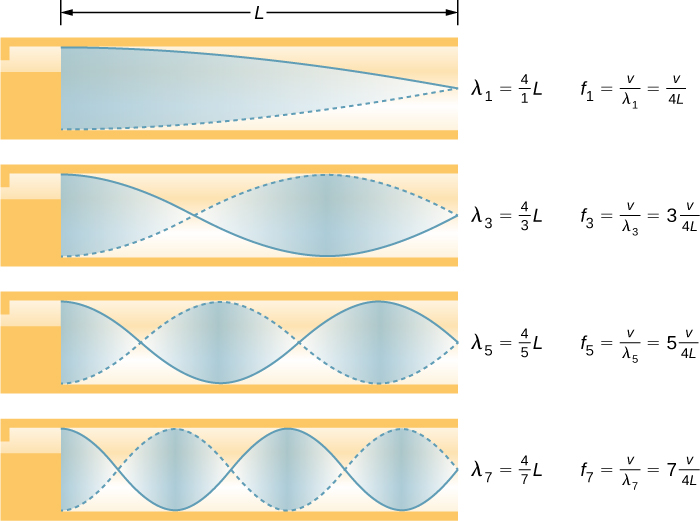

Some musical instruments, such as woodwinds, brass, and pipe organs, can be modeled as tubes with symmetrical boundary conditions , that is, either open at both ends or closed at both ends ( [link] ). Other instruments can be modeled as tubes with anti-symmetrical boundary conditions , such as a tube with one end open and the other end closed ( [link] ).

Resonant frequencies are produced by longitudinal waves that travel down the tubes and interfere with the reflected waves traveling in the opposite direction. A pipe organ is manufactured with various tubes of fixed lengths to produce different frequencies. The waves are the result of compressed air allowed to expand in the tubes. Even in open tubes, some reflection occurs due to the constraints of the sides of the tubes and the atmospheric pressure outside the open tube.

The antinodes do not occur at the opening of the tube, but rather depend on the radius of the tube. The waves do not fully expand until they are outside the open end of a tube, and for a thin-walled tube, an end correction should be added. This end correction is approximately 0.6 times the radius of the tube and should be added to the length of the tube.

Players of instruments such as the flute or oboe vary the length of the tube by opening and closing finger holes. On a trombone, you change the tube length by using a sliding tube. Bugles have a fixed length and can produce only a limited range of frequencies.

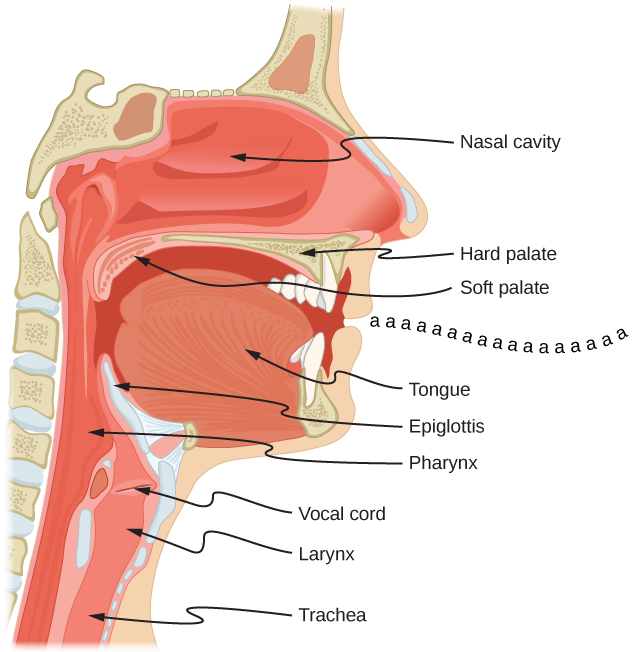

The fundamental and overtones can be present simultaneously in a variety of combinations. For example, middle C on a trumpet sounds distinctively different from middle C on a clarinet, although both instruments are modified versions of a tube closed at one end. The fundamental frequency is the same (and usually the most intense), but the overtones and their mix of intensities are different and subject to shading by the musician. This mix is what gives various musical instruments (and human voices) their distinctive characteristics, whether they have air columns, strings, sounding boxes, or drumheads. In fact, much of our speech is determined by shaping the cavity formed by the throat and mouth, and positioning the tongue to adjust the fundamental and combination of overtones. For example, simple resonant cavities can be made to resonate with the sound of the vowels ( [link] ). In boys at puberty, the larynx grows and the shape of the resonant cavity changes, giving rise to the difference in predominant frequencies in speech between men and women.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'University physics volume 1' conversation and receive update notifications?