| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

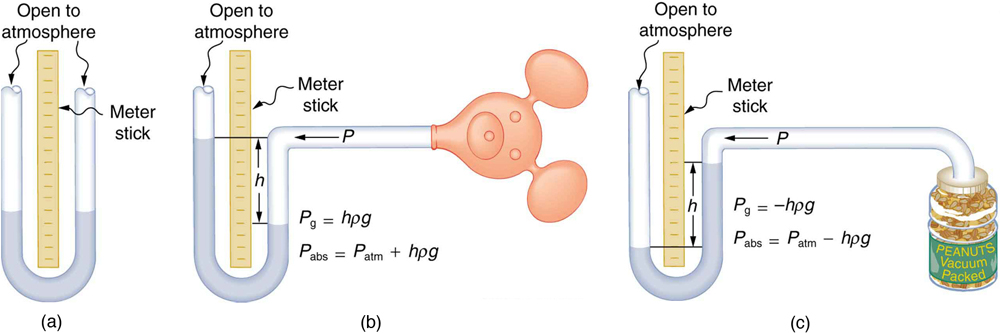

An entire class of gauges uses the property that pressure due to the weight of a fluid is given by Consider the U-shaped tube shown in [link] , for example. This simple tube is called a manometer . In [link] (a), both sides of the tube are open to the atmosphere. Atmospheric pressure therefore pushes down on each side equally so its effect cancels. If the fluid is deeper on one side, there is a greater pressure on the deeper side, and the fluid flows away from that side until the depths are equal.

Let us examine how a manometer is used to measure pressure. Suppose one side of the U-tube is connected to some source of pressure such as the toy balloon in [link] (b) or the vacuum-packed peanut jar shown in [link] (c). Pressure is transmitted undiminished to the manometer, and the fluid levels are no longer equal. In [link] (b), is greater than atmospheric pressure, whereas in [link] (c), is less than atmospheric pressure. In both cases, differs from atmospheric pressure by an amount , where is the density of the fluid in the manometer. In [link] (b), can support a column of fluid of height , and so it must exert a pressure greater than atmospheric pressure (the gauge pressure is positive). In [link] (c), atmospheric pressure can support a column of fluid of height , and so is less than atmospheric pressure by an amount (the gauge pressure is negative). A manometer with one side open to the atmosphere is an ideal device for measuring gauge pressures. The gauge pressure is and is found by measuring .

Mercury manometers are often used to measure arterial blood pressure. An inflatable cuff is placed on the upper arm as shown in [link] . By squeezing the bulb, the person making the measurement exerts pressure, which is transmitted undiminished to both the main artery in the arm and the manometer. When this applied pressure exceeds blood pressure, blood flow below the cuff is cut off. The person making the measurement then slowly lowers the applied pressure and listens for blood flow to resume. Blood pressure pulsates because of the pumping action of the heart, reaching a maximum, called systolic pressure , and a minimum, called diastolic pressure , with each heartbeat. Systolic pressure is measured by noting the value of when blood flow first begins as cuff pressure is lowered. Diastolic pressure is measured by noting when blood flows without interruption. The typical blood pressure of a young adult raises the mercury to a height of 120 mm at systolic and 80 mm at diastolic. This is commonly quoted as 120 over 80, or 120/80. The first pressure is representative of the maximum output of the heart; the second is due to the elasticity of the arteries in maintaining the pressure between beats. The density of the mercury fluid in the manometer is 13.6 times greater than water, so the height of the fluid will be 1/13.6 of that in a water manometer. This reduced height can make measurements difficult, so mercury manometers are used to measure larger pressures, such as blood pressure. The density of mercury is such that .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics' conversation and receive update notifications?