| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

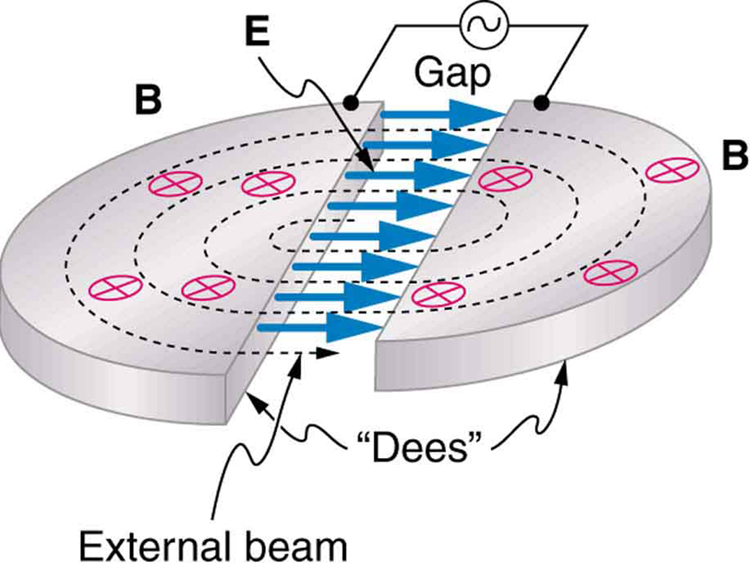

A synchrotron is a version of a cyclotron in which the frequency of the alternating voltage and the magnetic field strength are increased as the beam particles are accelerated. Particles are made to travel the same distance in a shorter time with each cycle in fixed-radius orbits. A ring of magnets and accelerating tubes, as shown in [link] , are the major components of synchrotrons. Accelerating voltages are synchronized (i.e., occur at the same time) with the particles to accelerate them, hence the name. Magnetic field strength is increased to keep the orbital radius constant as energy increases. High-energy particles require strong magnetic fields to steer them, so superconducting magnets are commonly employed. Still limited by achievable magnetic field strengths, synchrotrons need to be very large at very high energies, since the radius of a high-energy particle's orbit is very large. Radiation caused by a magnetic field accelerating a charged particle perpendicular to its velocity is called synchrotron radiation in honor of its importance in these machines. Synchrotron radiation has a characteristic spectrum and polarization, and can be recognized in cosmic rays, implying large-scale magnetic fields acting on energetic and charged particles in deep space. Synchrotron radiation produced by accelerators is sometimes used as a source of intense energetic electromagnetic radiation for research purposes.

Physicists have built ever-larger machines, first to reduce the wavelength of the probe and obtain greater detail, then to put greater energy into collisions to create new particles. Each major energy increase brought new information, sometimes producing spectacular progress, motivating the next step. One major innovation was driven by the desire to create more massive particles. Since momentum needs to be conserved in a collision, the particles created by a beam hitting a stationary target should recoil. This means that part of the energy input goes into recoil kinetic energy, significantly limiting the fraction of the beam energy that can be converted into new particles. One solution to this problem is to have head-on collisions between particles moving in opposite directions. Colliding beams are made to meet head-on at points where massive detectors are located. Since the total incoming momentum is zero, it is possible to create particles with momenta and kinetic energies near zero. Particles with masses equivalent to twice the beam energy can thus be created. Another innovation is to create the antimatter counterpart of the beam particle, which thus has the opposite charge and circulates in the opposite direction in the same beam pipe. For a schematic representation, see [link] .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?