| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

After visiting some of the applications of different aspects of atomic physics, we now return to the basic theory that was built upon Bohr’s atom. Einstein once said it was important to keep asking the questions we eventually teach children not to ask. Why is angular momentum quantized? You already know the answer. Electrons have wave-like properties, as de Broglie later proposed. They can exist only where they interfere constructively, and only certain orbits meet proper conditions, as we shall see in the next module.

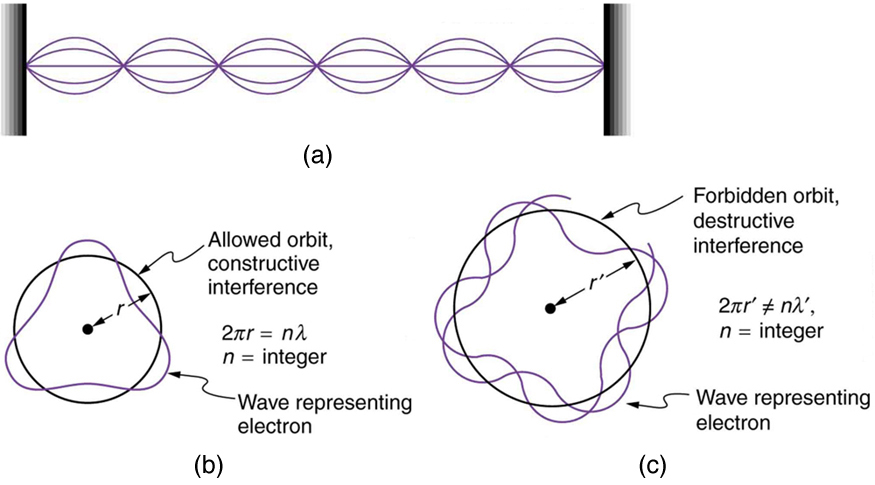

Following Bohr’s initial work on the hydrogen atom, a decade was to pass before de Broglie proposed that matter has wave properties. The wave-like properties of matter were subsequently confirmed by observations of electron interference when scattered from crystals. Electrons can exist only in locations where they interfere constructively. How does this affect electrons in atomic orbits? When an electron is bound to an atom, its wavelength must fit into a small space, something like a standing wave on a string. (See [link] .) Allowed orbits are those orbits in which an electron constructively interferes with itself. Not all orbits produce constructive interference. Thus only certain orbits are allowed—the orbits are quantized.

For a circular orbit, constructive interference occurs when the electron’s wavelength fits neatly into the circumference, so that wave crests always align with crests and wave troughs align with troughs, as shown in [link] (b). More precisely, when an integral multiple of the electron’s wavelength equals the circumference of the orbit, constructive interference is obtained. In equation form, the condition for constructive interference and an allowed electron orbit is

where is the electron’s wavelength and is the radius of that circular orbit. The de Broglie wavelength is , and so here . Substituting this into the previous condition for constructive interference produces an interesting result:

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?