| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

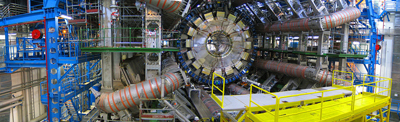

This idea of particle exchange deepens rather than contradicts field concepts. It is more satisfying philosophically to think of something physical actually moving between objects acting at a distance. [link] lists the exchange or carrier particles , both observed and proposed, that carry the four forces. But the real fruit of the particle-exchange proposal is that searches for Yukawa’s proposed particle found it and a number of others that were completely unexpected, stimulating yet more research. All of this research eventually led to the proposal of quarks as the underlying substructure of matter, which is a basic tenet of GUTs. If successful, these theories will explain not only forces, but also the structure of matter itself. Yet physics is an experimental science, so the test of these theories must lie in the domain of the real world. As of this writing, scientists at the CERN laboratory in Switzerland are starting to test these theories using the world’s largest particle accelerator: the Large Hadron Collider. This accelerator (27 km in circumference) allows two high-energy proton beams, traveling in opposite directions, to collide. An energy of 14 trillion electron volts will be available. It is anticipated that some new particles, possibly force carrier particles, will be found. (See [link] .) One of the force carriers of high interest that researchers hope to detect is the Higgs boson. The observation of its properties might tell us why different particles have different masses.

Tiny particles also have wave-like behavior, something we will explore more in a later chapter. To better understand force-carrier particles from another perspective, let us consider gravity. The search for gravitational waves has been going on for a number of years. Almost 100 years ago, Einstein predicted the existence of these waves as part of his general theory of relativity. Gravitational waves are created during the collision of massive stars, in black holes, or in supernova explosions—like shock waves. These gravitational waves will travel through space from such sites much like a pebble dropped into a pond sends out ripples—except these waves move at the speed of light. A detector apparatus has been built in the U.S., consisting of two large installations nearly 3000 km apart—one in Washington state and one in Louisiana! The facility is called the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Each installation is designed to use optical lasers to examine any slight shift in the relative positions of two masses due to the effect of gravity waves. The two sites allow simultaneous measurements of these small effects to be separated from other natural phenomena, such as earthquakes. Initial operation of the detectors began in 2002, and work is proceeding on increasing their sensitivity. Similar installations have been built in Italy (VIRGO), Germany (GEO600), and Japan (TAMA300) to provide a worldwide network of gravitational wave detectors.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics' conversation and receive update notifications?