| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The sharing hypothesis says that through song learning, birds can share songs with their neighbors, which enhances communication (Beecher&Brenowitz 2005). This is beneficial because territorial neighbors are usually important individuals in a songbird’s life. In fact, Beecher et al. (2000) found that greater song sharing among neighbors, but not repertoire size, predicted longer territorial possession. This sharing hypothesis, however, directly conflicts with the repertoire hypothesis, since sharing songs with neighbors is easier if both sides have a small repertoire.

DeWolfe BB, Baptista LF, Petrinovich L. 1989. Song development and territory establishment in Nuttall’s white-crowned sparrows. Condor. 91:397-407. © 1989 by the Cooper Ornithological Society. Reprinted with permission from the University of California

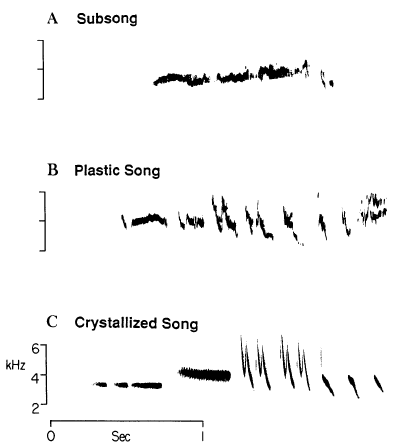

A songbird’s song goes through many developmental stages before arriving at the final, crystallized song (DeWolfe et al. 1989; Marler 1970b). Prior to this final stage, the developing song is considered plastic and subject to alteration. In fact, in many species, songs remain plastic for much of an adult’s life, allowing the bird to alter his songs throughout his life, perhaps to imitate his neighbor (Lehongre et al. 2009; Nordby et al. 2001). Many biologists recognize three stages of song development: subsong, plastic song, and crystallized song (Fig.3; DeWolfe et al. 1989).

Tutors, or sources of songs, are very important in social learning. Marler (1970b) shows that juvenile male songbirds that are acoustically isolated develop abnormal songs, while those that are raised with tape-recordings of songs develop songs normally. Juveniles usually learn their songs from older adults and show a tendency towards preferring conspecific models (Beecher&Brenowitz 2005). Soha&Marler (2001) found that white-crowned sparrow juveniles began showing preference toward conspecific songs prior to 20 days of age, when they are just beginning to memorize songs. Interestingly though, juvenile white-crowned sparrows can successfully learn the song of another species, such as the strawberry finch ( Amandava amandava ) provided that the tutors are live, as opposed to tape-recordings (Baptista&Petrinovich 1984). It seems that social interaction between tutors and tutee can even overcome genetic preference for conspecific songs. There is a general consensus among researchers that social interaction, and not mere exposure to a tutor song, is required for the best song-learning results in juvenile songbirds. For instance, in grasshopper sparrows, learning from live tutors results in more accurate imitation than learning from tape-recordings (Soha et al. 2009).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Mockingbird tales: readings in animal behavior' conversation and receive update notifications?