| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

A journey to brazil, 1853

Page 49

Page 98

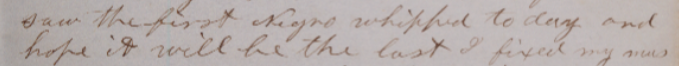

In a final example, taken from the latter portions of the journal, Dunham comes out more explicitly in opposition to the brand of discipline practiced by slave drivers in Brazil: “An old man that takes care of the sheep was whipped tonight I dont know what for perhaps for some accident that he could not possibly help the German appears to be an ugly rascal and will whip when there is no occasion and for that matter I think there never is any need of whipping after they are grown up” (135). Perhaps not surprisingly, owing to his professional position, Dunham expresses his disapproval of the brutality that he witnesses in practical, economic terms, generally speaking. He perceives these methods as inefficient, counterproductive means for controlling the labor force that forms the foundation of Brazil’s agricultural economy. It is never clear to what extent genuine humanitarian concern lies behind his condemnations; nor is it certain if he is directing these critiques toward the practices of slaveholders in the U.S. South. Regardless of his personal politics, Dunham would have known that his contemporary readers, inundated with the slavery question, would read such connections into his text, so these passages can, at a minimum, be understood with that broader reality in mind.

Even if Dunham, in his journal, cannot necessarily be classified as an anti-slavery writer, his chronicling of the violence and exploitation associated with the slave system does evoke the abolitionist texts that helped to define antebellum U.S. literary culture. Douglass’s Narrative of the Life and Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life , for example, portray in stark detail the series of physical, mental, and sexual abuses suffered by themselves as well as their friends and family. These authors sought to make their experiences as real and immediate as possible in order to convince their readers of slavery’s evils. Without that type of socio-political agenda behind his writings, Dunham does not approach the same level of detail found in Douglass and Jacobs; nonetheless, his observations contribute to an emerging portrait in the mid-nineteenth century of slavery as a cruel, demeaning, and unjust institution. One of the more striking moments from A Journey to Brazil , in which Dunham discovers copies of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Brazil, further motivates one to read the journal in relation to the anti-slavery literature of its day. “I find that Uncle Toms Cabin has got into Brazil and the people will read it,” Dunham writes (168). This exciting passage provides at least two opportunities to a class in the process of studying Stowe’s novel. A teacher could, of course, parallel the brutality of a character such as Simon Legree and the violent acts observed and recorded by Dunham. Yet another possibility would be to utilize this moment as evidence of Uncle Tom’s Cabin ’s global circulation, its worldwide impact on the issues of slavery and freedom. Paired with these classics of anti-slavery literature, Dunham’s journal takes on massive import to the study of nineteenth-century cultural production.

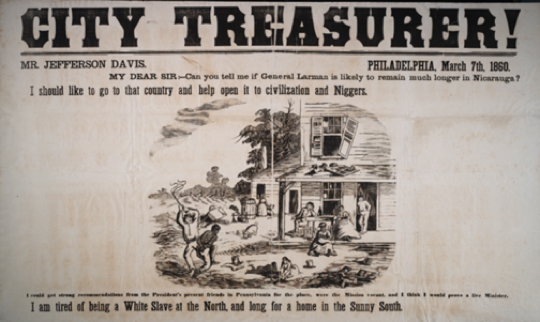

City treasurer [slavery poster], 1860

Another strategy for utilizing Journey to Brazil in the classroom would be as a vehicle for discussing slavery as an institution in other places within the Americas beyond the U.S. Dunham provides with some valuable firsthand observations of the inner workings of the Brazilian slave system. Brazil itself is, of course, an interesting case since it was the last country to officially abolish slavery, in 1888. More generally speaking, however, the journal will enable teachers to demonstrate the ways in which nineteenth-century slavery functioned as a transnational, hemispheric system. Dunham himself is a perfect example of how slavery in the Americas depended upon a transnational exchange of people, ideas, and technologies. Cultural critics have recently begun to explore in-depth the nature and ramifications of these dynamics, as can be seen in such studies as Matthew Guterl’s American Mediterranean: Southern Slaveholders in the Age of Emancipation and the collection of essays edited by Deborah Cohn and Jon Smith, Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies . Journey to Brazil provides yet another important case study for drawing connections among the slaveholding practices of the U.S. South and those of other slaveholding societies throughout the hemisphere.

Bibliography

Cohn, Deborah and Jon Smith, eds. Look Away! The U.S. South in New World Studies . Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2004.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass . Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999.

Guterl, Matthew. American Mediterranean: Southern Slaveholders in the Age of Emancipation . Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2008.

Hentz, Caroline Lee. The Planter’s Northern Bride . Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson, 1854.

Jacobs, Harriet. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl . Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2000.

Pickens, Lucy Holcombe. The Free Flag of Cuba . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2002.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin . New York: Oxford UP, 1998.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Permalink testing' conversation and receive update notifications?