| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Plagiarism has a long and complicated history. While the study of its evolution through the legal system is a field on its own, studying the appearance of plagiarism in historical texts can reveal the complicated, interconnected fabric of the early modern world, that is, transnational and transatlantic communication (books, newspapers, journals, letters, etc.), the loose idea of authorship and translation, the cosmopolitan figure, language and education, problematic international law (or lack thereof), etc. This module demonstrates how plagiarism can produce discussions on the larger world economy, law, literature, and culture.

Some interesting examples of historical plagiarism occur in Las mujeres españolas, portuguesas y americanas ( Spanish, Portuguese, and American Women ) and Historia moral de las mujeres ( The Moral History of Women ), documents found on the Our Americas Archive Partnership (OAAP) website (a collaborative digital archive focused on the Americas). Both books were published in the 19 th century and provide a description of women in the Americas.

Las mujeres specifically focuses on, as its subtitle clearly outlines, the “character, customs, typical dress, manners, religion, beauty, defects, preoccupations, and qualities of women from each of the provinces of Spain, Portugal, and the Spanish Americas.” It contains 20 chapters, written by different authors, each dedicated to a different country or region. The plagiarism in question occurs in the chapter titled “The Woman from Ecuador,” by Nicolas Ampuero (pp. 164-167). This plagiarism is particularly interesting, since it is not a simple case of borrowed text. Rather, it is complicated by language and translation.

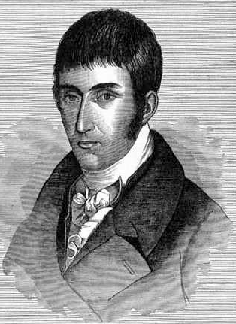

Francisco josé de caldas

Ampuero not only copied, but also translated a passage in Gaspard-Théodore Mollien’s Voyage dans la République de Colombia, en 1823 (“Voyage in the Republic of Colombia in 1823”) from French to Spanish. This passage, however, was Mollien’s summary of Francisco José de Caldas’s travels, recorded in Caldas’ own travel narrative, “Viaje de Quito a Popayan” (“Voyage from Quito to Popayan.”), which he originally wrote in Spanish. The text, therefore, goes from Spanish (Caldas), to French (Mollien), to Spanish (Ampuero), begging the question: was Ampuero aware of Caldas’ Spanish work? An examination of Mollien’s book shows that Ampuero must have assumed the existence of another text, since Mollien specifically refers to Caldas’ travel narrative and even includes his name in the summary. Here we can see an almost exact wording, minus Caldas’ name:

MOLLIEN: “After having passed Alto de la Virgen, Caldas entered Delek ” Mollien’s French text: « Après avoir dépassé l’Alto de la Virgen, Caldas entre à Delek » ( Voyage 293). ( Travels 446).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Print culture in the americas' conversation and receive update notifications?