| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

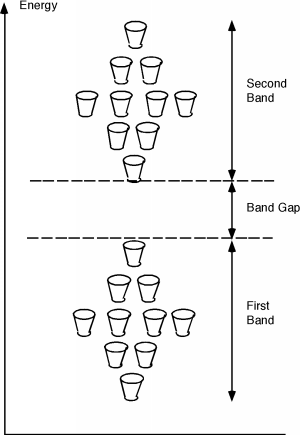

Firstly, unlike the case for free electrons, in a periodic solid, electrons are not free to take on any energy value they wish.They are forced into specific energy levels called allowed states, which are represented by the cups in [link] . The allowed states are not distributed uniformly in energy either. They are grouped into specific configurationscalled energy bands. There are no allowed levels at zero energy and for some distance above that. Moving up fromzero energy, we then encounter the first energy band. At thebottom of the band there are very few allowed states, but as we move up in energy, the number of allowed states first increases,and then falls off again. We then come to a region with no allowed states, called an energy band gap. Above the band gap,another band of allowed states exists. This goes on and on, with any given material having many such bands and band gaps.This situation is shown schematically in [link] , where the small cups represent allowed energy levels, and the vertical axis represents electron energy.

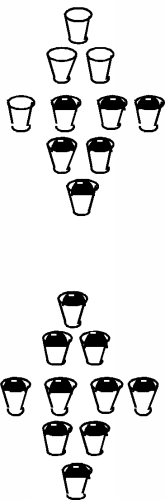

It turns out that each band has exactly 2 N allowed states in it, where N is the total number of atoms in the particular crystal sample we are talking about. (Since there are 10 cups in eachband in the figure, it must represent a crystal with just 5 atoms in it. Not a very big crystal at all!) Into these bandswe must now distribute all of the valence electrons associated with the atoms, with the restriction that we can onlyput one electron into each allowed state. This is the result of something called the Pauli exclusionprinciple. Since in the case of silicon there are 4 valence electrons per atom, we would justfill up the first two bands, and the next would be empty. If we make the logical assumption that the electrons will fill inthe levels with the lowest energy first, and only go into higher lying levels if the ones below are already filled. Thissituation is shown in [link] , in which we have represented electrons as small black balls with a "-" sign on them. Indeed, the first two bands are completelyfull, and the next is empty. What will happen if we apply an electric field to the sample of silicon? Remember the diagramwe have at hand right now is an energy based one, we are showing how the electrons are distributed inenergy, not how they are arranged spatially. On this diagram we can not show how they will move about, but only how they willchange their energy as a result of the applied field. The electric field will exert a force on the electrons and attemptto accelerate them. If the electrons are accelerated, then they must increase their kinetic energy. Unfortunately, there are noempty allowed states in either of the filled bands. An electron would have to jump all the way up into the next (empty) band inorder to take on more energy. In silicon, the gap between the top of the highest most occupied band and the lowest unoccupiedband is 1.1 eV. (One eV is the potential energy gained by an electron movingacross an electrical potential of one volt.) The mean free path or distanceover which an electron would normally move before it suffers a collision is only a few hundred angstroms ( ca . 300 x 10 -8 cm) and so you would need a very large electric field (several hundred thousand V/cm) in order for the electron to pick up enough energy to"jump the gap". This makes it appear that silicon would be a very bad conductor of electricity, and in fact, very puresilicon is very poor electrical conductor.

A metal is an element with an odd number ofvalence electrons so that a metal ends up with an upper band which is just half full of electrons. This is illustrated in [link] . Here we see that one band is full, and the next is just half full. This would be the situation for theGroup 13(III) element aluminum for instance. If we apply an electric field to these carriers, those near the top of thedistribution can indeed move into higher energy levels by acquiring some kinetic energy of motion, and easily move fromone place to the next. In reality, the whole situation is a bit more complex than we have shown here, but this is not too farfrom how it actually works.

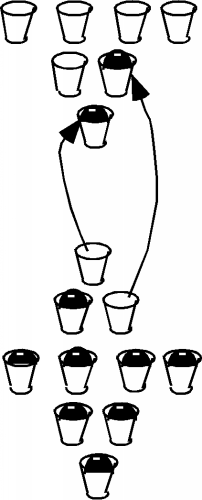

So, back to our silicon sample. If there are no places for electrons to "move" into, then how does silicon work as a"semiconductor"? Well, in the first place, it turns out that not all of the electrons are in the bottom two bands. Insilicon, unlike say quartz or diamond, the band gap between the top-most full band, the next empty one is not so large. As wementioned above it is only about 1.1 eV. So long as the silicon is not at absolute zero temperature, some electrons near the topof the full band can acquire enough thermal energy that they can "hop" the gap, and end up in the upper band, called theconduction band. This situation is shown in [link] .

In silicon at room temperature, roughly 10 10 electrons per cubic centimeter are thermally excited across the band-gap at any one time. It should be noted thatthe excitation process is a continuous one. Electrons are being excited across the band, but then they fall back down into emptyspots in the lower band. On average however, the 10 10 in each cm 3 of silicon is what you will find at any given instant. Now 10 billion electrons per cubic centimeterseems like a lot of electrons, but lets do a simple calculation. The mobility of electrons in silicon isabout 1000 cm 2 /V.s. Remember, mobility times electric field yields the average velocity of the carriers. Electric field has units of V/cm, so with these units we get velocity in cm/s as we should. The charge on an electron is 1.6 x 10 -19 coulombs. Thus from [link] :

If we have a sample of silicon 1 cm long by (1 mm x 1mm) square, it would have a resistance, [link] , which does not make it much of a "conductor". In fact, if this were all there was to the silicon story, we could pack up andmove on, because at any reasonable temperature, silicon would conduct electricity very poorly.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Chemistry of electronic materials' conversation and receive update notifications?