| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The shoots and roots of plants increase in length through rapid cell division within a tissue called the apical meristem ( [link] ). The apical meristem is a cap of cells at the shoot tip or root tip made of undifferentiated cells that continue to proliferate throughout the life of the plant. Meristematic cells give rise to all the specialized tissues of the plant. Elongation of the shoots and roots allows a plant to access additional space and resources: light in the case of the shoot, and water and minerals in the case of roots. A separate meristem, called the lateral meristem, produces cells that increase the diameter of stems and tree trunks. Apical meristems are an adaptation to allow vascular plants to grow in directions essential to their survival: upward to greater availability of sunlight, and downward into the soil to obtain water and essential minerals.

As plants adapted to dry land and became independent of the constant presence of water in damp habitats, new organs and structures made their appearance. Early land plants did not grow above a few inches off the ground, and on these low mats, they competed for light. By evolving a shoot and growing taller, individual plants captured more light. Because air offers substantially less support than water, land plants incorporated more rigid molecules in their stems (and later, tree trunks). The evolution of vascular tissue for the distribution of water and solutes was a necessary prerequisite for plants to evolve larger bodies. The vascular system contains xylem and phloem tissues. Xylem conducts water and minerals taken from the soil up to the shoot; phloem transports food derived from photosynthesis throughout the entire plant. The root system that evolved to take up water and minerals also anchored the increasingly taller shoot in the soil.

In land plants, a waxy, waterproof cover called a cuticle coats the aerial parts of the plant: leaves and stems. The cuticle also prevents intake of carbon dioxide needed for the synthesis of carbohydrates through photosynthesis. Stomata, or pores, that open and close to regulate traffic of gases and water vapor therefore appeared in plants as they moved into drier habitats.

Plants cannot avoid predatory animals. Instead, they synthesize a large range of poisonous secondary metabolites: complex organic molecules such as alkaloids, whose noxious smells and unpleasant taste deter animals. These toxic compounds can cause severe diseases and even death.

Additionally, as plants coevolved with animals, sweet and nutritious metabolites were developed to lure animals into providing valuable assistance in dispersing pollen grains, fruit, or seeds. Plants have been coevolving with animal associates for hundreds of millions of years ( [link] ).

One of the most exciting recent developments in paleobotany is the use of analytical chemistry and molecular biology to study fossils. Preservation of molecular structures requires an environment free of oxygen, since oxidation and degradation of material through the activity of microorganisms depend on the presence of oxygen. One example of the use of analytical chemistry and molecular biology is in the identification of oleanane, a compound that deters pests and which, up to this point, appears to be unique to flowering plants. Oleanane was recovered from sediments dating from the Permian, much earlier than the current dates given for the appearance of the first flowering plants. Fossilized nucleic acids—DNA and RNA—yield the most information. Their sequences are analyzed and compared to those of living and related organisms. Through this analysis, evolutionary relationships can be built for plant lineages.

Some paleobotanists are skeptical of the conclusions drawn from the analysis of molecular fossils. For one, the chemical materials of interest degrade rapidly during initial isolation when exposed to air, as well as in further manipulations. There is always a high risk of contaminating the specimens with extraneous material, mostly from microorganisms. Nevertheless, as technology is refined, the analysis of DNA from fossilized plants will provide invaluable information on the evolution of plants and their adaptation to an ever-changing environment.

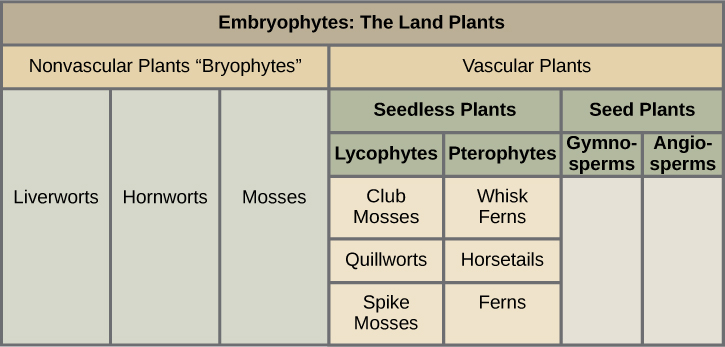

Land plants are classified into two major groups according to the absence or presence of vascular tissue, as detailed in [link] . Plants that lack vascular tissue formed of specialized cells for the transport of water and nutrients are referred to as nonvascular plants . The bryophytes, liverworts, mosses, and hornworts are seedless and nonvascular, and likely appeared early in land plant evolution. Vascular plants developed a network of cells that conduct water and solutes through the plant body. The first vascular plants appeared in the late Ordovician (461–444 million years ago) and were probably similar to lycophytes, which include club mosses (not to be confused with the mosses) and the pterophytes (ferns, horsetails, and whisk ferns). Lycophytes and pterophytes are referred to as seedless vascular plants. They do not produce seeds, which are embryos with their stored food reserves protected by a hard casing. The seed plants form the largest group of all existing plants and, hence, dominate the landscape. Seed plants include gymnosperms, most notably conifers, which produce “naked seeds,” and the most successful plants, the flowering plants, or angiosperms, which protect their seeds inside chambers at the center of a flower. The walls of these chambers later develop into fruits.

To learn more about the evolution of plants and their impact on the development of our planet, watch the BBC show “How to Grow a Planet: Life from Light” found at this website .

Land plants evolved traits that made it possible to colonize land and survive out of water. Adaptations to life on land include vascular tissues, roots, leaves, waxy cuticles, and a tough outer layer that protects the spores. Land plants include nonvascular plants and vascular plants. Vascular plants, which include seedless plants and plants with seeds, have apical meristems, and embryos with nutritional stores. All land plants share the following characteristics: alternation of generations, with the haploid plant called a gametophyte and the diploid plant called a sporophyte.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Bi 101 for lbcc ilearn campus' conversation and receive update notifications?