| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

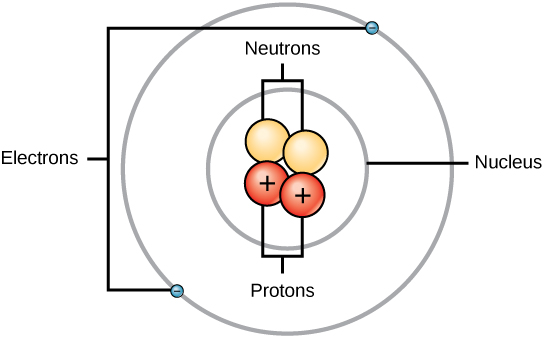

An atom is composed of two regions: the nucleus , which is in the center of the atom and contains protons and neutrons , and the outermost region of the atom which holds its electrons in orbit around the nucleus, as illustrated in [link] . Atoms contain protons, electrons, and neutrons. The only exception is hydrogen (H), which is made of one proton and one electron, with no neutrons.

Protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass, about 1.67 × 10 -24 grams. Scientists arbitrarily define this amount of mass as one atomic mass unit (amu) or one Dalton, as shown in [link] . Although similar in mass, protons and neutrons differ in their electric charge. A proton is positively charged whereas a neutron is uncharged. Therefore, the number of neutrons in an atom contributes significantly to its mass, but not to its charge. Electrons are much smaller in mass than protons, weighing only 9.11 × 10 -28 grams, or about 1/1800 of an atomic mass unit. Hence, they do not contribute much to an element’s overall atomic mass. Therefore, when considering atomic mass, it is customary to ignore the mass of any electrons and calculate the atom’s mass based on the number of protons and neutrons alone. Although not significant contributors to mass, electrons do contribute greatly to the atom’s charge, as each electron has a negative charge equal to the positive charge of a proton. In uncharged, neutral atoms, the number of electrons orbiting the nucleus is equal to the number of protons inside the nucleus. In these atoms, the positive and negative charges cancel each other out, leading to an atom with no net charge.

Accounting for the sizes of protons, neutrons, and electrons, most of the volume of an atom—greater than 99 percent—is, in fact, empty space. With all this empty space, one might ask why so-called solid objects do not just pass through one another. The reason they do not is that the electrons that surround all atoms are negatively charged and negative charges repel each other.

| Protons, Neutrons, and Electrons | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge | Mass (amu) | Location | |

| Proton | +1 | 1 | nucleus |

| Neutron | 0 | 1 | nucleus |

| Electron | –1 | 0 | orbitals |

Atoms of each element contain a characteristic number of protons and electrons. The number of protons determines an element’s atomic number and is used to distinguish one element from another. Thus, an atom with only one proton and one electron is always going to be an atom of hydrogen; an atom with two electrons and two protons is an atom of helium, etc. Unlike the fixed number of electrons and protons in atoms of any particular element, however, the number of neutrons is variable. An atom of hydrogen can have zero, one or two neutrons. Different numbers of neutrons will not change the charge, but will change the mass of an atom. These different forms, varying only in the number of neutrons, are called isotopes. Together, the number of protons and the number of neutrons determine an element’s mass number, as illustrated in [link] . Note that the small contribution of mass from electrons is disregarded in calculating the mass number. This approximation of mass can be used to easily calculate how many neutrons an element has by simply subtracting the number of protons from the mass number. Since an element’s isotopes will have different mass numbers, scientists also determine the relative atomic mass or standard atomic weight , which is the calculated mean of the mass numbers for its naturally occurring isotopes. Often, the resulting number contains a fraction. For example, the relative atomic mass of chlorine (Cl) is 35.45 because chlorine is composed of several isotopes, some (the majority) with an atomic mass of 35 (17 protons and 18 neutrons) and some with an atomic mass of 37 (17 protons and 20 neutrons).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?